A Building Experiment to Support Families

A novel approach to land use could help address housing shortages.

By Theo Mackey Pollack, writer, lawyer, and urban planner based in New Jersey

A decade ago, it was rare to hear much talk about the role of land-use policies on the cost of housing in America. Things have changed. Today, it’s almost a given that zoning and other regulatory restrictions are at odds with a growing nation’s need for new homes—a subject increasingly of interest to millions of young Americans. Some states and communities have lately acknowledged the connection passing laws aimed at relaxing limits on home construction. Targets have included the blocks around train stations in commuter towns and erstwhile single-family-only neighborhoods. These are worthy efforts, but they are not nearly enough.

For more than a generation, a tightening housing market has posed a growing obstacle for many Americans. One group that has been particularly impacted is young adults. In more and more parts of the country, decent housing for young people who wish to move out of their parents’ homes, and especially for young couples who wish to marry and start families, has drifted out of reach. While these trends have long impacted working people in certain high-cost coastal regions, the cost of housing in America has surged nationwide since the pandemic. By one account, the cost of buying a home rocketed more than 47% from 2020 through 2024. Rental prices have also gone up sharply.

Intuitively, it seems evident that the housing market has become a key factor in a range of concerning social phenomena, including fewer young families, high outmigration rates from vibrant regions, fraying social ties, and fewer stable communities. Moreover, housing challenges that once mainly impacted working-class people in places like New York City and California now reach deep into the heartland and impact those with higher incomes. In many sectors of the economy, a sustained rise in prices will lead to a response in production that, ultimately, helps to restore a healthier equilibrium. Why is such a correction now elusive for housing?

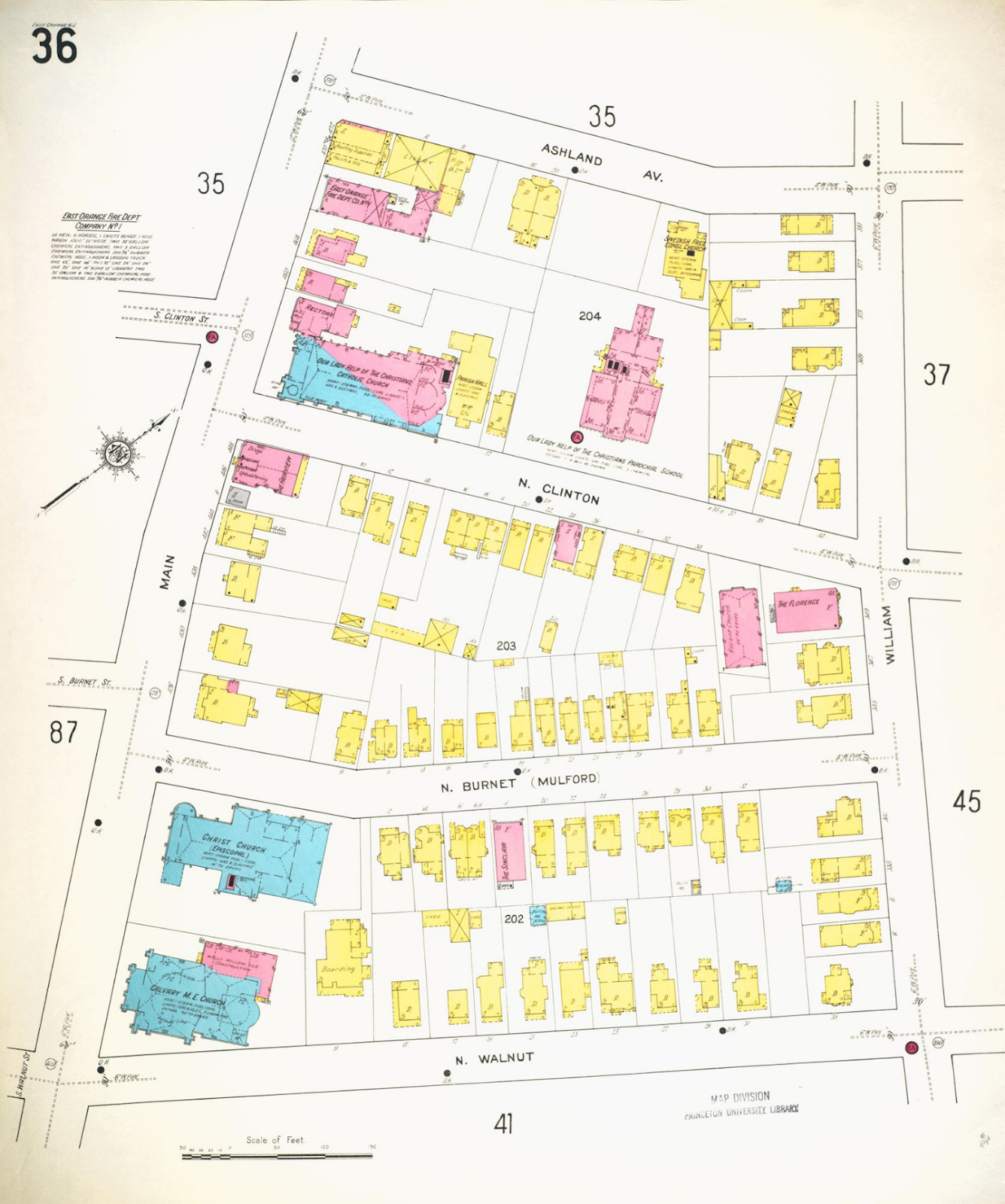

For much of American history, the common law governing new structures offered a permissive model for builders. A few types of development—mainly hazards and nuisances—were proscribed, but most construction on private property was allowed. Your land was yours, after all. This was a free country. In the 1910s, urban planners began to introduce a much more prescriptive framework. With zoning, public laws would increasingly specify what could—and more importantly, what could not—be built on any piece of property.

For more than a century since, land use regulations have distorted American neighborhoods. In direct response to the 1926 Supreme Court decision that permitted zoning, local governments began to limit new multifamily houses. In traditional towns and cities, urban growth became less responsive than it once was, as new arrivals overwhelmed what existing structures could accommodate, and in communities laid out since World War II, strip malls, parking lots, matching houses, and garden apartments have become the norm.

During the postwar era, at least, the economics of a prescriptive model were able to coexist with broad affordability because undeveloped land remained plentiful. During these years, metropolitan regions could expand outward, and space for future suburbs remained plentiful. Today, some entire metropolitan regions have exhausted their erstwhile safety valve of buildable land within commuting distance of the region’s core, and the persistence of prescriptive land use policies has fueled exorbitant housing costs and extreme commutes by inhibiting the timely and resourceful modification of existing neighborhoods to accommodate an increasing number of households.

As older, established regions have failed to grow and adapt, a lack of affordable housing has contributed to the mass out-migration of middle- and working-class Americans from some of the nation’s most dynamic economic centers, concentrated in the Northeast and California. This internal migration, especially by working-class Americans, and the lack of affordable housing that has driven it, has almost certainly fueled more than a generation of demand for illegal labor in the same regions. Meanwhile, homelessness stands at record levels.

The inability of so many Americans to find homes in their own communities must be contributing to the national crescendo of rage and despair. In the short term, restrictive land use policies appear to offer stability by preventing evidence of change. In the longer term, they distort and dissolve coherent communities by blocking necessary adjustments to the local housing stock and displacing people, one household at a time, through rising rents, property taxes, and home prices. Officials have responded with half measures and glib explanations, but the status quo is not sustainable. The fabric is fraying.

To unwind a generational housing crisis, stabilize communities, and allow new places to develop meaningful character again, Americans need to find our way to an urban growth framework that instantiates the ancient wisdom of traditional urbanism. This will mean recovering a framework that is essentially responsive to the real people who live and work in a particular place. This is how towns and cities were built for most of the history of civilization, and it was the template for many American neighborhoods—including nearly all our coherent towns and cities that predate zoning.

Perhaps our chief obstacle is that we have so thoroughly replaced the simple legal matrix that once supported traditional urban growth that we have forgotten its benefits; and we have few, if any, examples of traditional urbanism that are living and adapting in our own time. We recognize that the regulatory morass has become stifling, yet we do not wish to respond too radically, throwing open the gates and encouraging a free-for-all that would destroy the superficial semblance of order that the status quo provides. And so we chip away at the edges. So far, our attempts at reform have been far too modest. The status quo has endured.

It’s worth beginning with something bold.

Before zoning, builders might be subject to building codes, fire codes, and the possibility of lawsuits. In some places, private land was subject to restrictive covenants or easements—worked out among private owners—that limited uses or shaped development, such as subdivision requirements that bound future owners to avoid commercial uses; easements to preserve access to sunlight, running water, or a scenic view; or the more prescriptive sorts of rules that some homeowners associations impose on their members today. Otherwise, land was built up at the discretion of individuals. This approach to urban growth ensured an adequate supply of new homes, with building patterns driven by economics and demographics. It produced some slums, yes, but it also gave rise to beautiful neighborhoods, many ordinary places, and a rich variety of workshops, theaters, stables, churches, shops, and the other bits and pieces of a complex urban civilization. Places reflected the variety of people and communities.

Today, we should experiment with returning that concept to fashion: call it a Common-Law Building Zone. Typically, state legislatures delegate land use powers to municipalities with varying degrees of latitude. Hence, an innovative state legislature interested in fixing our current land-use regime could authorize a local government (or several) to designate a district where building regulations are pared back to a very lean, traditional framework that resembles the common-law approach to urban growth. Proscriptive rules against hazards and nuisances would be kept strong, but rules to prescribe land uses and dimensions would be mostly repealed.

Ideally, the first Common-Law Building Zone would be undertaken in a growing region. This could help ensure adequate demand while encouraging a contrast to emerge between the zone and its typical, prescribed surroundings. A limited introduction would allow early adopters to select locations that are ripe for change and open to the experiment. The approach could be refined in response to experience. How might the starting framework look?

First, the wholesale removal of prescriptive regulatory obstacles would be essential. This would require a community and a local administration willing to embrace a zone of dynamic growth, rather than merely tinkering around the edges. Welcoming the kinds of practical, responsive changes that are the ordinary processes of urban growth, without the resistance of bureaucratic friction, would reduce the time and expense of improvements. More builders would get in on the game; this would distribute the task, fostering more variety and a spirit of competition.

For instance, in the Common-Law Building Zone an owner could erect a small apartment house where a detached house had previously been; or subdivide a large parcel into numerous narrow building lots to support a block of new rowhouses; or replace an aging strip mall with sidewalk-hugging storefronts, with studio apartments and offices upstairs (as in a typical American downtown). Parking requirements and lot-coverage prescriptions would be terminated. The idea would be to incubate a living dynamic of responsive growth and adaptation. This is how neighborhoods once changed, and it could be again.

Next, guidance about drafting and enacting traditional legal devices, like easements and restrictive covenants, and on design concepts that contribute to harmonious patterns, could be made actively available through workshops for builders and residents. A century ago, such intentional supports were not needed in the unselfconscious framework of traditional urbanism, but today they could help to reintroduce the customs and incremental patterns that have been forgotten by a century of deference to master plans and traffic engineering. In keeping with the spirit of an urbanism driven by civil society, these offerings would be made within an approach that prioritized builder discretion.

Finally, while recovering much more freedom of action for builders and residents, the Common-Law Building Zone’s framework would maintain key advances that Americans have come to expect from modern laws: namely, the prevention of hazards and nuisances. Thus, industrial uses and other sources of smoke, noise, and odors would not be permitted in quiet neighborhoods. Projects that exceed a traditional urban scale (that is, full-lot buildings that exceed about five stories) would be channeled to locations with adequate supporting infrastructure, or the basis for its provision.

In service to the same end, building codes would remain fully effective, prohibiting slum tenements and other unsafe structures, while establishing baselines for occupancy, egress, and fire safety. Floodplain requirements would remain. In short, a common-law building zone would preserve the concrete benefits delivered by modern building techniques, while eliminating the arbitrary meddling of officials in the latitude to safely and resourcefully improve one’s property.

Would such an experiment be popular? It might. To be certain, its parameters, the spirit in which it was pursued, and the aptitude of administration would matter. Even in an ideal scenario, some would resist. That said, the exorbitant housing costs, extreme commutes, and onerous bureaucracy that many Americans now endure could lead many to appreciate a rediscovery of urban property rights. In the short term, such an experiment would likely benefit local land values, as parcels once restricted to narrow uses enticed builders to envision more valuable projects. Rising property values tend to please existing owners, compensating even those who recoiled from specific changes. At a time when Americans are increasingly interested in reducing regulation—and when even some radical attempts to cut red tape have gained traction—there could be a unique opening.

On a somewhat longer timeline, the ability to build smaller, less expensive homes would let more people to stay in their community, even with rising land values. The freedom to modify one’s home would help growing families, assuring parents that they could always add a bit of extra space. A stream of new apartments could help young people move out of parents’ homes without leaving the region, while seniors could downsize from homeownership, freeing up larger houses for young families. Perhaps counterintuitively, the introduction of more flexibility around the use of private property would help restore a measure of community stability, knitting not just families but communities more closely together, and helping to address the epidemic of loneliness that darkens so many American places.

On its own, an experiment in one, or several, Common-Law Building Zones might be expected to have limited impacts on regional costs or commutes. That said, people imitate success. If a more traditional approach to urban growth yielded rising land values, an infusion of smaller units, and more genuine freedom—all while proving that the sky would not fall in towns or cities that exercised an intentionally lighter regulatory touch—it would offer an enviable model. Its replication, more widely, could begin to meaningfully unwind some of the dysfunction that has settled over American communities in the absence of adequate housing.

In the realm of land use, rules that shape the built environment have often proven more brittle than supple, but in a contest between unbending regulations and responsive individuals, it is the community that is more prone to break. Up and down the economic ladder, high costs and few options have incentivized millions to leave the places where they had the deepest ties and might have contributed to stronger communities. With building patterns that responded more directly to local needs, a sense of opportunity would be restored, and the specters of displacement, stagnation, and even homelessness would begin to recede.

For more than a generation, middle- and working-class Americans have found themselves with diminishing options in metropolitan housing markets. Recently, the same dynamics have begun to impact more affluent urban professionals and those living in smaller communities. Whether they choose to endure or relocate, Americans’ deeply personal choices about their careers, families, and communities are absurdly subordinated to the effects of inscrutable land use policies. Common-Law Building Zones, built on the wisdom of an older approach, would introduce a starker contrast. In doing so, they could show us what else is possible.