America’s Techno-Industrial Crossroads

Washington’s historic opportunity to reverse American decline

By Kelvin Yu, fellow at the Foundation for American Innovation

Is America still the world’s leading technological and industrial power? As late as 2011, when China first surpassed the United States in manufacturing output, the answer would have been an unqualified yes. Today, the picture is far less clear.

As China’s industrial might ascended in recent decades—last year reaching a manufacturing surplus almost equivalent to Britain’s entire GDP—we decided to let ours decline. For too long, our political leadership trusted an “invent here, make there” model that neglected the profound connection between innovation and production. This mistake has cost us dearly.

For too long, our political leadership trusted an “invent here, make there” model that neglected the profound connection between innovation and production. This mistake has cost us dearly.

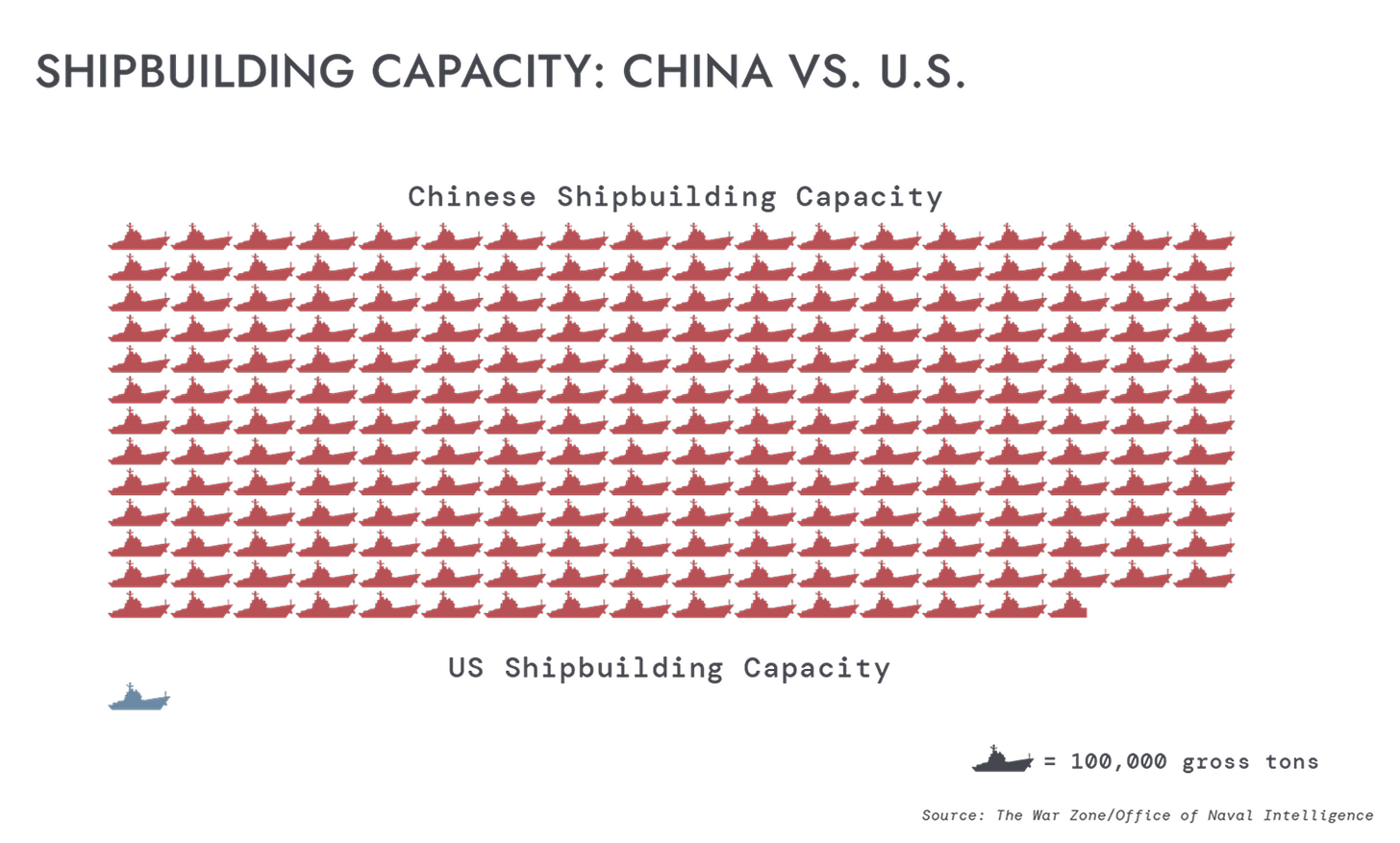

America is wholly unprepared for wartime production needs. With current manufacturing capacity, it would take at least eight years to replenish major defense program inventories at surge production rates. Nearly all Navy ship construction projects are years behind schedule. Decades of consolidation have reduced the number of defense prime contractors from more than 50 during the Cold War to six today, the number of surface ship suppliers from eight to two, and the number of tactical missile producers from 13 to three. Fully 90% of all missiles come from three sources, creating inefficient oligopolies and inflated prices. While our defense industrial base slumbers in peacetime, China’s operates on wartime urgency, generating 23,000% more shipbuilding capacity; its Jiangnan Shipyard alone surpasses all US shipyards combined.

These problems are exacerbated by failing energy infrastructure across our country. U.S. grid capacity is already reaching the breaking point in many areas. Yet it is getting increasingly costly and difficult to build basic electric infrastructure: annual transmission line construction has fallen nearly since 2013. Rapidly growing demand from industrial projects and technological innovation, particularly artificial intelligence, will require much greater supply to come online, in amounts that can only be met with a combination of traditional and alternative sources. China, recognizing this reality, is currently building 23 next-gen nuclear reactors, compared to zero in America, where nuclear plants cost 6 to 12 times more to construct today than in the 1960s. Last year, a single Chinese company, Tongwei, installed nearly the same amount of solar capacity as all of America combined.

Meanwhile, China leveraged its superior production capabilities to scale up whole new industries and surpass America in a growing portfolio of critical technologies. From 2007 to 2018, its contributions to value-added manufacturing of the iPhone—one of the most complex pieces of hardware on earth—grew from 4% to 25%. Deepseek’s R1 model, released during President Trump’s second inauguration, exceeded OpenAI’s most advanced model on multiple benchmarks at of the cost. China dominates global markets for rare earths refinement, 5G networks, consumer drones, and lithium-ion batteries. In recent years, China achieved global firsts in quantum-encrypted satellite communication and landing spacecraft on the far side of the moon, proving its ability to push technological frontiers. Its industries are supported by a vast technical workforce: in 2020, China graduated 3.5 million STEM students (4x times the US total) and roughly 50,000 STEM PhDs (2.5x the US total, excluding international students).

These successes result from a deep, unified seriousness among Chinese elites that the leading techno-industrial nation will win the 21st century. From Deng Xiaoping to Xi Jinping, the Chinese Communist Party’s top brass have consistently stated that we are in the midst of a techno-industrial revolution—and that “seizing this rare opportunity” is the “decisive factor for national strength,” the “foundation for a world power,” and a requirement to achieving the “great rejuvenation” of the Chinese nation. This seriousness has allowed China to repeatedly defy American expectations about its technological capabilities, from the Semiconductor Manufacturing International Corporation’s 7nm semiconductors to Deepseek’s V3 and R1 models, despite stringent export controls.

This does not imply imitating China, as US innovation does not depend on top-down economic mandates, forced tech transfers, or intellectual property theft. What America must take from China is not its methods but its attitude.

For too long, many in Washington have lacked the same degree of seriousness. This does not imply imitating China, as US innovation does not depend on top-down economic mandates, forced tech transfers, or intellectual property theft. What America must take from China is not its methods but its attitude. A serious country would not allow overbearing red tape to hamper hundreds of billions of critical infrastructure investments. It would not educate the world’s brightest only to kick them out shortly thereafter—often into the arms of our adversaries, with disastrous consequences. It would not have fetishized financialization—neutering industrial capacity and leaving communities hollow. It would not allow its students to hit all-time-low math scores just last year, at a time when such foundations are most critical.

Such mistakes undermine America’s tradition of technological progress—a tradition that history shows is the foundation of our national prosperity. It was the First and Second Industrial Revolutions that catapulted Britain, then America, to global superpower status. For 20th-century Americans, nuclear bombs, industrial machines, and space shuttles secured existential military victories, widespread economic growth, and national pride. In recent decades, democracies such as Israel, South Korea, Taiwan, and Japan all became techno-industrial envies of the world by force-multiplying free markets with strategic state action.

Fortunately, the tide has begun turning. Continued failures at home, emerging threats abroad, and an intensifying arms race over emerging technologies such as AI have sparked a resurgent bipartisan awakening that drastic actions are needed to secure America’s techno-industrial future. Both the Trump and Biden administrations have taken bold steps—the former has initiated a sweeping agenda to reincentivize private investment in domestic industry, while the latter emphasized historic supply-side investments into chip factories, energy, and infrastructure.

However, neither approach is sufficient in isolation. Take American shipbuilding, which suffers from immensely inflated costs due to parts of the Jones Act, aging infrastructure, lack of modern tooling, labor shortages, and persistent shifting requirements from the Navy. Public subsidies without structural reform cannot fix these chronic inefficiencies. Likewise, private-sector incentives alone cannot close the funding gap to rebuild naval capacity, let alone on strategic timelines like a 2027 Taiwan scenario. America’s techno-industrial challenges are not just about trade or spending—they reflect deeper structural bottlenecks and insufficient state capacity.

Policymakers must pursue an all-of-the-above strategy. No single policy lever is enough. The scale, urgency, and complexity of today’s techno-industrial challenges require coordinated action across public investment, regulatory reform, and private mobilization. TSMC’s U.S. expansion highlights the potential of such an approach—initially drawn by CHIPS and Science Act subsidies to start a fab in Arizona, the company recently announced a further $200B investment, spurred by tariff pressure and accelerated permitting promises.

Policymakers must pursue an all-of-the-above strategy. No single policy lever is enough. The scale, urgency, and complexity of today’s techno-industrial challenges require coordinated action across public investment, regulatory reform, and private mobilization.

Despite our headwinds, America retains significant assets that, if strategically harnessed, can unleash a new century of prosperity. We still boast the world’s most advanced military, capital markets, and research ecosystem. We still lead many of the world’s emerging technologies, from AI to hypersonics to quantum computing (although the gap is shrinking fast). The world’s best and brightest still flock to us. The “spirit of enterprise” that Tocqueville saw as America’s most distinctive feature remains strong. Public policy should therefore seek to complement these forces, not replace them.

The Trump-Vance administration and the 119th Congress have a historic opportunity at their feet. A generational leadership transfer in Congress, the ongoing bipartisan realignment, and the arrival of bold outsiders in Washington have given America a chance to rebuild its techno-industrial leadership.

From the citizenry’s perspective, technology—like other pursuits—should support economic growth, national security, and community flourishing. Effective policy requires discerning which innovations to privilege and the most effective ways to support them. After all, not all technology is equally valuable for the good of the nation. Anduril’s arsenal is far more critical to American interests than Netflix, even though the latter is worth 15 times as much.

The road ahead will not be easy. The realities of American labor costs, permitting burdens, and cultural clashes reveal a stark reality: reindustrialization requires not just the ability to make things, but to make them cost-competitively. TSMC’s failed 1998 Oregon plant and the 2019 documentary American Factory exemplify these challenges. In contrast, China reduces unit costs by deploying more industrial robots annually than the rest of the world combined, alongside exploiting low wages, lax safety standards, and forced labor.

Our values rightly dissuade us from competing on those terms. Instead, we must beat them the same way we achieved industrial dominance in the past: through investing (both public and private) and adopting productivity-enhancing technologies. The War Finance Corporation and Reconstruction Finance Corporation were instrumental public institutions that catalyzed American industry during WWI and WWII, respectively. Many pillars of modern manufacturing, including CNC machining and CAD/CAM software, originated from joint Air Force/MIT research. Scaling industrial innovation, investing in a skilled domestic workforce, and easing regulatory restraints on development are the keys to improving the economics of industrial power to reduce immutable costs and make reindustrialization financially feasible.

Scaling industrial innovation, investing in a skilled domestic workforce, and easing regulatory restraints on development are the keys to improving the economics of industrial power to reduce immutable costs and make reindustrialization financially feasible.

Weak industrial capacity poses a grave risk to national security. Industrial power in peacetime, even if it is dedicated to commercial goods, can be quickly converted to meet surge production needs. This was our overwhelming strategic advantage in World War II. As one British analyst observed, “The Battle of Waterloo was won on the playing fields of Eton, but World War II was won on the drawing boards of Detroit.” Our success ramping 155mm artillery shell production in the past two years is a reminder of what American industry can achieve at its best.

The industrial base is not the only defense-relevant arena for innovation. Military supremacy—as shown in American domination during the Gulf War, ongoing conflicts in Israel and Ukraine, and wargames for a potential Taiwan-strait conflict—is largely due to technological asymmetries. As AI, quantum computing, biotech, and other emerging technologies continue to advance, we must ensure they are adapted for offensive and defensive advantage—and that they get into the hands of warfighters as quickly and efficiently as possible. Their requisite supply chains must remain stateside or in allied nations.

Finally, we must not forget the foundation of technological supremacy: frontier research, both basic and applied. Although China’s research ecosystem still lags behind America’s, it is rapidly closing the gap in dozens of areas. America, meanwhile, continues to struggle with the infamous “valley of death” problem, where promising technologies stall in R&D and fail to reach production. As a 2023 Department of Defense report on the topic aptly urged, “the need for reform is immediate.”

A version of this foreword can be found on www.rebuilding.tech.