On Budgeting for Defense, U.S. Should Think Wider, Not Just Bigger

A stronger defense industrial base will require an economy- and alliance-wide investment strategy.

The Trump administration’s recently released National Security (NSS) and National Defense (NDS) strategies make clear that the United States is no longer defining its foreign policy around abstract, unrealistic ideals, but rather on clear-eyed assessments of concrete realities and constraints. At the core of this shift is the recognition that the U.S. has overextended itself in foreign commitments while underinvesting in its own industrial base. Going forward, maintaining U.S. national security and defenses will require a broader investment strategy for reindustrialization that spreads risk and responsibility beyond U.S. taxpayers and moves past procurement frameworks that have left the defense base overstretched and fragile.

The NDS states, “essential to [President Trump’s common sense] approach is being realistic about the scale of the threats we face and the resources available to meet those threats.” The NSS elaborates further, arguing that past generations of leaders “overestimated America’s ability to fund, simultaneously, a massive welfare-regulatory-administrative state alongside a massive military, diplomatic, intelligence, and foreign aid complex” while pursuing globalist policies that “hollowed out the very middle class and industrial base on which American economic and military preeminence depend.”

These limits and constraints are not admitted defensively or in retreat from our nation’s strategic interests, but as a reality check for advocates of the “rules-based international order” at home and abroad who insist that the U.S. bear the world’s burdens while its population’s cost of living and debts continue to rise and their opportunities diminish. While grand visions of empire appeal to foreign policy elites and have benefitted foreign nations under the U.S. security umbrella, they do not suit a nation conceived as an independent republic of national citizens.

For decades, the real costs of maintaining peace—and the strength necessary to protect it—have chiefly been borne by the United States. As Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent recently noted, the U.S. has spent $22 trillion more on defense since 1980 than the rest of NATO, the equivalent of roughly two-thirds of our national debt. U.S. burden shouldering also extends into the economic realm, as the United States’ currency and assets have accrued to savers around the world, leaving the U.S. with massive trade deficits and a negative $27 trillion net international investment position.

The U.S.’s outsized role in supporting the international order is not disputed. In his screed against the United States at Davos last week, even Canadian Prime Minister Mark Carney acknowledged, “American hegemony, in particular, helped provide public goods, open sea lanes, a stable financial system, collective security, and support for frameworks for resolving disputes.” NATO Secretary-General Mark Rutte added in recent days that European nations would need to spend 10% of their GDP on defense without the United States, double what many of them have only recently (and begrudgingly) pledged to spend.

When the economies and militaries of current U.S. allies were devastated by World War II and communism was spreading across the globe, this arrangement made sense. But the “Marshall Plan” mentality should have ended in the early 1970s, when the United States began facing its own fiscal constraints and other industrial economies began to rival U.S. manufacturing power. Unfortunately, the decades since have demonstrated that nations are often reluctant to carry their weight if another country steps in—and U.S. leaders were ready to do so. Worse, with defense concerns off the table, many such nations have pursued immigration, climate, and censorship policies that further undermine the strength of the alliance. Meanwhile, the United States is now left spending more annually on servicing its debt than on defense or Medicare, even as its industrial base erodes and its population’s economic security weakens. An end must come to U.S.-funded civilizational welfare.

Both strategy documents highlight the erosion of the U.S. defense industrial base, which underpins the need for strategic prioritization and burden sharing. This marks the return to a strategy embraced by generations of American statesmen who understood that making things matters. As Alexander Hamilton argued in his 1791 Report on Manufacturers, “not only the wealth; but the independence and security of a Country, appear to be materially connected with the prosperity of manufactures. Every nation, with a view to those great objects, ought to endeavour to possess within itself all the essentials of national supply… and in the various crises which await a state, it must severely feel the effects of any such deficiency.”

As recently noted by U.S. Trade Representative Jamieson Greer, under the “American System” envisioned in Hamilton’s report and later championed by Henry Clay and Abraham Lincoln, industrial output per capita increased 525% from 1750 to 1860, and industrial production surged another 1,030% from 1860 to 1910. In contrast, U.S. industrial production has flatlined since the turn of the twenty-first century, when globalization entered full force and China was admitted to the WTO. National and economic security are advanced by industrial knowledge and production, not by debt-fueled consumption and NGOs.

The failure of past U.S. leaders to heed Hamilton’s warning has fueled Americans’ frustration with the much-vaunted neoliberal “international order.” Despite U.S. investments in that post-war order, our nation has fallen behind in many key respects. While the United States still retains the most lethal and strategically capable military in the world—as recent operations in Iran and Venezuela have shown—the industrial base required to scale that power has been steadily eroded by decades of offshoring, financialization, and corporate consolidation. This has resulted in real and growing vulnerabilities if the U.S. were to face a prolonged conflict with a peer or near-peer adversary, as evidenced by NATO’s inability to match Russia’s munitions production during the war in Ukraine, despite Russia’s smaller economy and more limited network of allies.

Our military’s procurement system and the contractors staffed through the Pentagon’s revolving door have become bloated, inefficient, and ossified, channeling profits into executive salaries, dividends, and stock buybacks rather than investing in the infrastructure and R&D that would support the next-generation’s insurmountable warfighter. President Trump has taken notice, stating in December:

I’m going to meet with the defense prime contractors…and we’re going to be talking about production schedules because they’re too slow. We have many countries, allies, that are wanting to buy… and the only way they’re going to be able to do that is to build new plants… They don’t want to build new plants because that’s expensive, so we’re going to be discussing production schedules. We’re going to be discussing capex spending. We’ll be discussing the pay to executives where they’re making 45 and 50 million dollars a year and not being able to build quickly. If they’re going to make that kind of money, they have to build quickly... We’re also going to be discussing dividends. We want the dividends to go into the creation of production facilities... We’re also going to be talking about buybacks... I don’t want them to buy back their stock. I want them to put the money in plant and equipment so they can build these planes fast, rapidly, like immediately… So we don’t want to have executives making 50 million dollars a year issuing big dividends to everybody and also doing buybacks and then saying, well, we don’t have the money to build the plant. They’ve got to build plants… And that’s it... They’re going to start spending money on building airplanes and ships and the things that we need, not in 10 years, not in 15 years. We need them now.

The defense sector is a particularly glaring example of recent corporate strategies given the immediate implications for military procurement; however, the issues with corporate executive pay, dividends, and stock buybacks are not limited to the defense sector. As American Compass has explained, since 2009, a majority of publicly traded U.S. firms by market capitalization have allowed their capital base to erode in favor of shareholder returns as opposed to maintaining or growing capital investment. This is further reflected in the decline of nonresidential investment in the wider economy, from an average of 4.3% of GDP in the 1970s and early 1980s to an average of 2.3% from 2009-2017. This trend even extends to the more capital-intensive manufacturing sector.

Betting on Industrial Depth

To meet the challenges of the twenty-first century, the United States needs greater capacity for both scale and innovation. Doing so will require a sustained restructuring of incentives across the entire economy, not merely within the defense sector. Ditching stock buybacks, which were illegal before 1982, and better aligning executive compensation with actual output should be economy-wide norms. Ultimately, a defense industrial base will require a broader industrial base.

If our inputs, equipment, and industrial knowledge are still outsourced in essential industries, the U.S. final assembler and intellectual property owner won’t do us much good when we need to scale in the event of an actual conflict or war. And while increased investment in the defense industrial base is imperative, taxpayers cannot shoulder that burden alone. Restoring the level of capacity required will demand a coordinated, economy-wide and alliance-wide effort—one capable of approaching the scale that underwrote the Allied victory in World War II. As President Roosevelt exhorted in his 1942 annual budget message,

Powerful enemies must be outfought and outproduced. Victory depends on the courage, skill, and devotion of the men in the [Allied] forces, and of the others who join hands with us in the fight for freedom. But victory also depends upon efforts behind the lines—in the mines, in the shops, on the farms. We cannot outfight our enemies unless, at the same time, we outproduce our enemies... We must outproduce them overwhelmingly, so that there can be no question of our ability to provide a crushing superiority of equipment in any theater of the world war.

The defense budget is a great tool in the U.S. industrial policy arsenal, but it is a limited tool for fully reviving supply chains essential to both national and commercial security. Alongside greater capacity for ships, planes, and drones, the United States must continue to protect and expand its capacity to produce semiconductors, critical minerals and rare earths, nuclear energy components, communications infrastructure, autos, steel and aluminum, and pharmaceutical precursors.

Not every key industry will appear to be on the technological frontier, but as we learned after losing the battery market to China when it was still dominated by consumer electronics, we don’t know from which sector the next era-defining technology will emerge. The safest bet the United States can make is on industrial depth—building industrial capacity and expertise throughout the wider $31 trillion U.S. economy, not just the $1 trillion defense budget.

A sovereign wealth fund, national development bank, or expanded use of the Office of Strategic Capital and Development Finance Corporation could help diffuse funding more widely, rather than channeling it to entrenched incumbents with poor performance records. In the long run, the objective remains to achieve competitive markets that stand on their own, rather than state entrenchment or reliance on peacetime defense budgets.

New investments should be matched by better prioritization of existing funding and resources, consistent with the administration’s goal of reprivatizing the economy. As of March 2025, the United States has over 243,000 military personnel stationed in foreign nations and manages over 560,000 facilities that collectively cover a landmass the size of Virginia. As the U.S. calls on its allies to assume the security burdens of their regions, it should seek opportunities to sell and transfer the maintenance of existing assets to trusted allies.

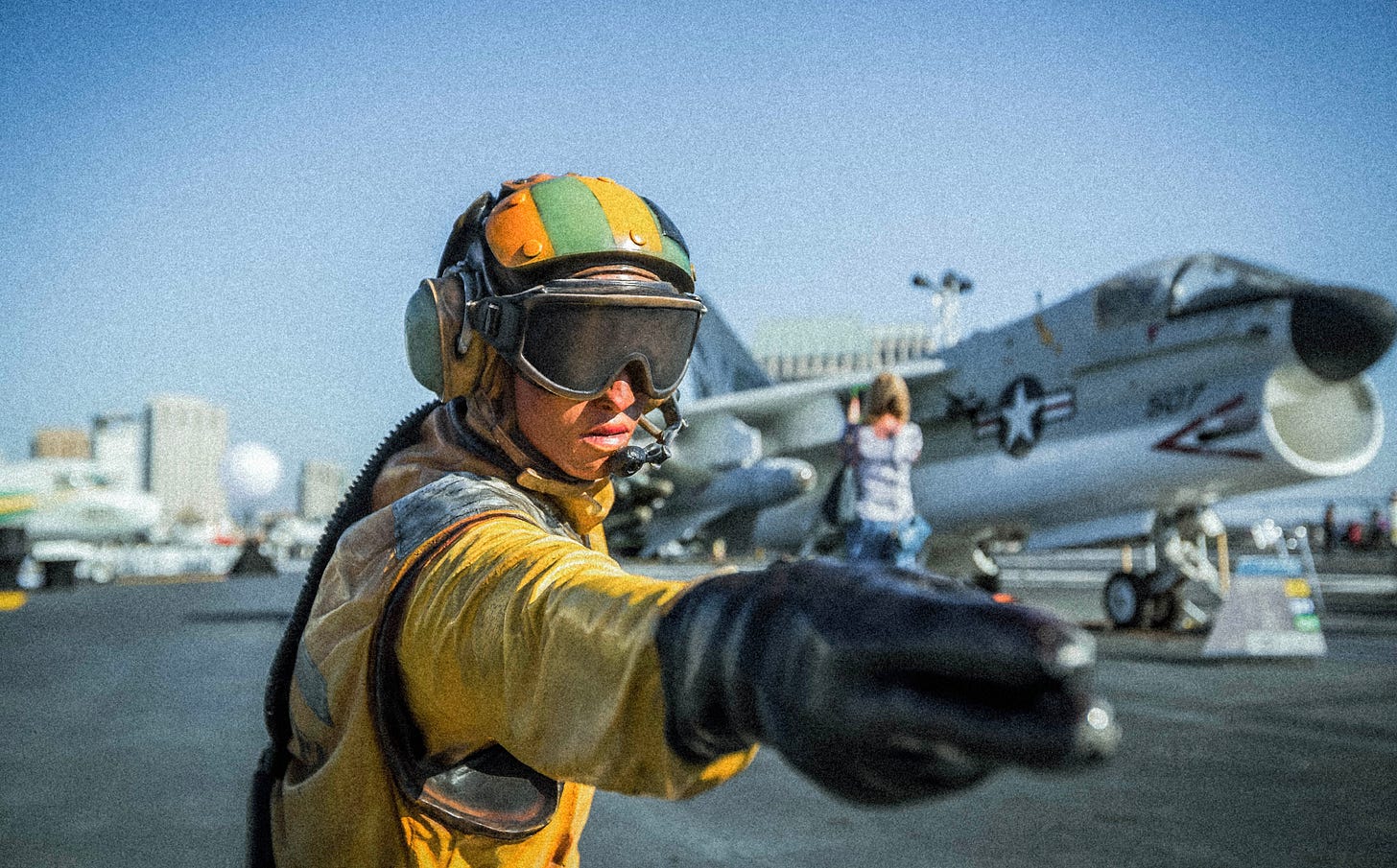

Defense funding should be approached conceptually, working backward from concrete strategic objectives and desired denial capabilities. Legacy systems should be evaluated for practical use under today’s rapidly changing battlefield conditions, with an eye toward being “careful stewards” of “precious resources” as the NDS suggests. If unmanned aerial and underwater drones and missiles continue to advance, it will not be in the strategic interest of the U.S. to sink hundreds of billions into legacy manned aircraft and fleets that can be neutralized in a matter of days or hours without corresponding defensive upgrades.

Navy Secretary John Phelan’s recent mention of a “high-low mix” of higher-cost ships and cheaper models produced in volume and acquired through more dynamic and innovative contractors sounds like a prudent course. A “Golden Dome,” like the space program before it, also seems like a worthwhile investment, especially given the success of Israel’s defense system and the ascendance of drones and missiles in contemporary warfare.

The reality of the national debt as a security vulnerability also cannot be ignored. Biden-era inflation has made clear that Washington’s resistance to serious program cuts or raising taxes alongside spending increases eventually comes at a cost—a cost that also bears electoral consequences. Some will counter that this month’s massive spike in gold prices is a signal that the administration’s pivot is not working and has undermined confidence in the U.S.-led order. But a weaker dollar will support this transition, even if it raises import costs and thus some prices, by making U.S. goods more price competitive in foreign markets and thereby increasing demand for American exports.

Given the massive U.S. trade deficit, the resulting increase in net exports should directly contribute to higher GDP growth, incomes, jobs, output, and ultimately productivity. If anything, tremors in U.S. treasury markets that supposedly foreshadow a world less willing to finance U.S. deficits underscore the urgency of rebalancing toward production. If relatively more government and private-sector spending goes toward investment in production capacity, and the economy sees real productivity gains as a result, growth should outpace spending increases in the long run and keep further inflation in check.

Peace Through Strength, Strength Through Production

If industry is reshored to America, more Americans will have private sector jobs and incomes that spill over into other sectors of the economy. While it will require bigger upfront investments, functional industrial policy should not grow government but instead pull more of the economy toward the private sector while decreasing government spending in the long run—especially after decades of U.S. income, jobs, and wealth flowing overseas to countries with industrial policies of their own.

The Trump administration’s willingness to acquire equity stakes with its investments also promises to cover the taxpayer-fronted principal with interest while clearing a path to eventual self-sufficiency for U.S. firms in sectors facing predatory foreign competition and dumping. Done correctly—and alongside the president’s trade and energy policies—a broad approach to industrial policy can increase the rate of production faster than consumption while maintaining overall growth. This means consumption and the U.S. standard of living could continue to increase even as our economy rebalances toward production and away from debt-financed consumption.

There is also great potential for innovation waiting to be tapped. As economic strategist David Goldman has argued, “without exception, every important technology of the digital age began with a DARPA or NASA subsidy: the semiconductor, CMOS manufacturing of semiconductors, the graphical user interface, semiconductor lasers, optical networks, LED and plasma displays, and the Internet itself.” Financial analyst Michael McNair further argues, “the transcontinental railroad emerged from massive federal land grants. During WWII, the Defense Plant Corporation built thousands of factories, leased them to private firms, then sold them back after the war. When Japan threatened our semiconductor industry in the 1980s, Sematech used DoD funding and guaranteed demand to restore American competitiveness.”

If the burden of rebuilding the U.S. industrial base is shared across the allied economies that it will help supply and protect—through foreign tariff revenue, defense and procurement commitments, greenfield investment, and potentially higher fees on U.S. asset holdings—and across the private sector through wider investment in production capacity instead of financial assets, the U.S. could find itself in a better position economically, fiscally, and militarily.

As allies meet new defense spending benchmarks, demand for U.S. defense production will be better guaranteed, making front-end investment more sensible. This will not be for the sole interest of the United States, but for the civilizational integrity of its alliances as they face continued threats from rival powers with very different values, governments, and economic practices. The United States is not asking Europe to bear more burden than the United States; it is asking them to carry their portion of the burden. The U.S. wants a stronger Europe, not a weaker one. It wants Europe to have more weight to throw around, not less. All allies should understand what public goods are indeed being provided and why they are essential to each nation’s economic and geopolitical security.

Likewise, domestically, the stable markets that buttress America’s financial institutions are not a given. They are governed by a system of laws and norms understood by all to redound to the nation’s benefit. In return, it is not unreasonable for our leaders to ensure our economic institutions recognize our nation’s broader interests, including obligations to American workers, communities, and national security.

Restricting American investment and IP-sharing with non-market economies and firms would also help redirect more investment toward U.S. shores. Americans should also pay higher taxes on foreign investments than on investments made in the United States. If taxpayers are going to continue to invest here, there should be little tolerance for investments by American firms that undermine the benefits of those investments.

Budgeting for security through productive investment is the only strategy capable of sustaining American independence, prosperity, and leadership in an emerging multipolar world. If the United States fails to reverse course, it will continue to face a future where China’s state-run firms—often fused with its military—dominate key industries while U.S. innovation withers, leaving national security compromised by dependence on strategic adversaries. Both of the administration’s strategy documents recognize that achieving peace through strength in the coming years will demand budgetary realism, rerouting corporate investment, greater burden-sharing by U.S. allies, and the ambition to rebuild the innovative, industrial foundations of our power. As the NDS concludes, “this effort will require nothing short of a national mobilization.”

Drones are the future. No longer tactical, they are strategic. And a couple orders of magnitude cheaper than alternatives.

The lesson from Ukraine is that drones are the future of warfare, and lots and lots of small, cheap ones at that. Perhaps that means territorial conquest will be harder, perhaps not. As always military budgeting focuses on the last war, not the next one. Necessity, the mother of invention, proven again in Ukraine.