Meet the Post-Trump, Working-Class GOP

Pennsylvania’s blue-collar voters went for Trump, but whether they stick with the GOP will depend on what the party does next.

By Ethan Dodd, journalist

On Election Day Eve, I was covering Kamala Harris’s rally in Pittsburgh at the Carrie Blast Furnaces, a testament to the city’s steel glory, now a museum. The Harris campaign made a last-minute venue switch there to connect the San Francisco attorney to the union roots of western Pennsylvania. It felt forced, like the rally Harris held with President Joe Biden months earlier at the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers union hall on Labor Day. That’s where I met Shawn Cribbs Jr. for the first time. “They haven’t earned my vote. Kamala is reading off a script,” the 20-year-old IBEW member told me at the time, noting “a lot of the classic, old-school, hard-working union guys were big fans of Joe Biden.”

But Cribbs couldn’t stomach Trump’s “objectively incorrect statements,” like claiming that the 2020 election was stolen. By November 4, he had decided to vote for Harris. “I like her first-time homebuyer policy and that she’s making more of an effort to stop the war in Gaza. And she’s younger and claims she won’t take my guns,” he texted. Then, unsolicited, he added, “but she has a lot to prove, especially cause if Vance runs against her next election cycle I’m voting for him.”

With Star Wars lightsabers and gym pics on his Instagram, Cribbs is what you’d expect from a Gen-Z union guy. If it were JD Vance versus Harris, there would be no question, he said. “He’s held back by Trump but needs the platform,” Cribbs said. “He’s much more coherent, very young, speaks like he would be willing to work with people, and actually grew up from a struggling environment and can back it.”

Though he credited Biden’s infrastructure dollars with repairing a collapsed Pittsburgh bridge, Cribbs saw gas and grocery prices go up under Biden’s watch. “I’m dumb. I’m just a guy. I don’t care about the charts,” Cribbs confessed. “People need to see the results first-hand to understand why they need to vote for a certain president.”

Harris spoke for less than ten minutes that night at the Carrie Blast Furnaces before handing the show off to Katy Perry, who sang “Dark Horse” to strobe lights below the dormant man-made volcano that once smelted iron ore. A “Steelworkers for Harris” sign lit up one of the shadowy brick buildings as I walked into the ill-fated party, but there were no steelworkers in sight. They were nine miles away, standing behind Trump at his rally in Pittsburgh’s PPG Arena.

Looking back now, it was an omen that would be confirmed the following night: Democrats had lost the working class.

That’s worth repeating: Democrats lost the working class. Since Franklin Delano Roosevelt stepped in to save “the forgotten man,” the Democratic Party has been identified with the vulnerable, whether the wage worker, farmer, or professional forced to join the ranks of the unemployed and destitute. Trump’s Republican Party, really the America First movement, has been the death knell of that Democratic Party.

If the exit polls don’t lie, Trump won 51% of voters who make less than $100,000 a year. He won 56% of those without college degrees. He made inroads with virtually every demographic group, even those long considered safely Democratic, like women, Hispanics, and young people. And he won the undeniable arbiter of democratic legitimacy—the popular vote—the first Republican to do so in 20 years. Riding Trump’s coattails, Republicans gained their coveted trifecta in Congress. Naturally, Trump has called this mandate “massive.”

But he’s wrong. Though Trump won the most votes he’s ever received—77 million—that’s less than Joe Biden’s 84 million in 2020. Trump also didn’t win the majority of the vote (49.9%). In fact, his margin (1.5%) was the fourth smallest popular vote margin since 1960, smaller than Biden’s, smaller than the late Jimmy Carter’s, and, yes, smaller even than Hillary Clinton’s. Though most Americans support the mass deportation of illegal immigrants, they don’t support many of Trump’s other chief policies, notably tariffs. These facts should give the Trump administration pause.

The 2024 election was not an electoral blowout, but a cultural victory. This is what I observed from covering the 2024 election at its epicenter in western Pennsylvania. For the first time, Trump could definitively claim the mantle of the working class. He dislodged the Democratic coalition and stole its identity. He forced millions of Americans to question their allegiance to the party, what it stands for, and whether it stands for them. It’s just a question if he can keep them.

The way people talk about JD Vance is very different from the way they talk about Trump. With Trump, it’s in your face: “the country needs him now.” With Vance, it’s more intimate. He’s familiar, like a distant cousin you know will do big things one day. Talking about him, folks sound calmer, curious—hopeful even. I encountered this on my first trek out to western Pennsylvania in late August when I saw Vance speak in Erie.

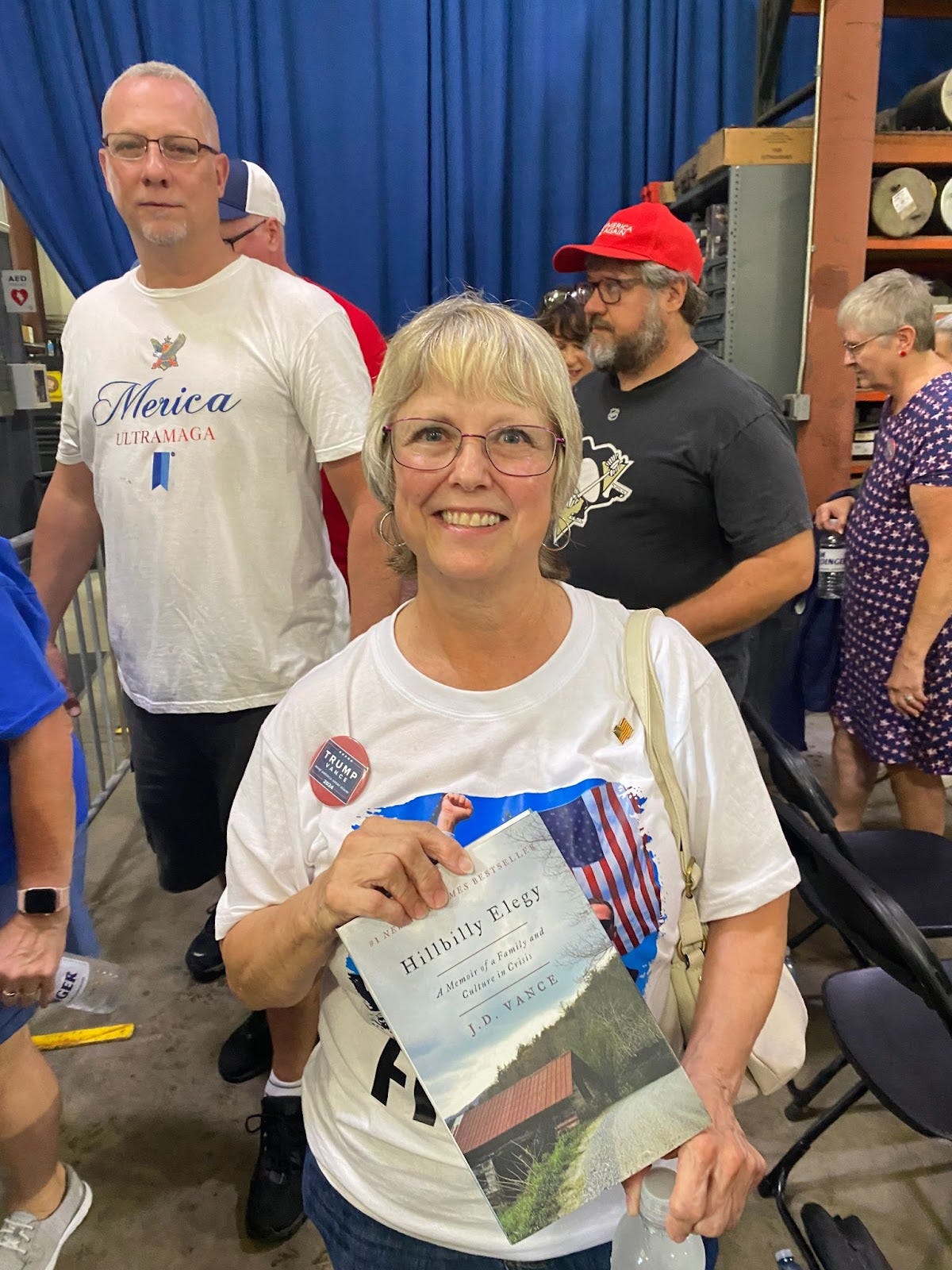

“I can relate to him so well. I relate to him totally,” said Chris Knight, 68, beaming after Vance blamed Harris for fentanyl coming across the border at a small rally in a warehouse garage decorated with two semi-trucks. She was clutching her hard copy of Vance’s memoir Hillbilly Elegy, which details his origin story raised by a mom addicted to opioids. The school cook said her daughter struggled with heroin for years and “now helps other people so they don’t go down this path.”

Too many here have trod that path. Hollowed out by automation and competition with China, Erie County has shed jobs and people for decades. Among all of Pennsylvania’s counties, it had the highest rate of opioid overdoses and the second most accidental drug deaths in 2023. 90% of those drug-related deaths were due to fentanyl. Just one day in June saw seven overdose deaths in six hours.

“We saw Mary’s brother two years ago in a body bag. Opioids. Fentanyl poisoning. And nobody talks about it,” Dan Doyle, a fracker who opened for Vance, shared about his wife. “Nobody cares,” added Mary, a stay-at-home mom. “You see JD Vance talking about it. Trump talks about it. You don’t see the Dems talking about it.”

“The whole Republican Party is changing, and we’re addressing the opioid problem,” Mary said. “Now the Democrats are the elitists and the Republicans are for the working man.”

Mary’s twin daughters, both 16, said that the Republican Party has trouble reaching younger voters like them but that Vance was different. “I can’t see [Trump] in my shoes at all. I can’t understand how to be him because he’s so rich. JD Vance understands it more,” Elena said. Not only is he younger, but “his background story is also really inspiring to all of us—that everyone has a chance.”

That’s why the Harris campaign tried to tar and feather Vance in Erie just a week later. “This isn’t about name calling or anything,” Harris’ VP pick Governor Tim Walz told his much larger and visibly affluent crowd, but “it’s weird to be obsessed with people’s personal lives. It’s weird to be obsessed with people’s healthcare choices.”

The Minnesota governor had first rolled the “weird” attack line out against Vance in late July, not long after clips of Vance surfaced criticizing the leadership of “childless cat ladies.” As far as I could tell from the Erie Democratic crowd, the attack was working. One teacher defended it: “If that’s what gets to them, if that’s the word that gets under their skin. They’re way worse than weird.”

But the power of “weird” was limited. “People like me are tired of the name-bashing,” Barry LaCastro, a local union business manager, said as his men broke down the set of the Walz rally and loaded equipment onto trucks headed for Pittsburgh. LaCastro hadn’t even heard the “weird” line. “Maybe that’s because of Trump saying woke all the time?” he suggested. Like a third of his employees, LaCastro said he was undecided, torn between wanting Trump’s economy but not wanting the man and his “venom.”

A movement needs a leader. Trump, 78, is now the oldest president to be sworn in, five months older than Joe Biden was when he assumed office. MAGA, America First, whatever you want to call it, will need a successor. And many voters in Pennsylvania thought Vance was the man for the job.

“To me, Vance is us. I can relate to him. I can’t really relate to Trump,” said Scott Sigmund, a retired IT worker, after Vance spoke at the opulent Pennsylvanian hotel in Pittsburgh. “I never knew my father, was abused by my stepdad, enlisted right out of high school,” he explained, comparing his life trajectory to Vance’s. “He’s the epitome of America.” The Tennessee native said Vance’s Yale education means “he can connect with the intellect” and speak the language of college-educated voters in Steel City, now known for its universities and hospitals.

Cathy Collins, a special-needs life coach and Pittsburgh native, called Vance a new and improved Trump, articulate and without the name-calling. “What Trump lacks, JD has,” she said. “We want Vance as president next time around.”

“Vance really is the future of the Republican Party,” said Luc Doolittle, a senior at PennWest Clarion, a public university in western Pennsylvania. The 23-year-old chairman of the Jefferson County Republican Party took a summer course that had him attend the Republican National Committee just 72 hours after Trump survived an assassination attempt in Butler, Pennsylvania. He believes that Trump chose Vance as his running mate to protect the shift he had started toward a working-class GOP.

Mocking the stereotype of the country-club Republican, Doolittle said Vance cements the party on America First principles of economic nationalism and military restraint. “Vance is the guy that can keep the Trump coalition together and possibly expand it with his more polished America First message,” he said. Vance is more pro-worker and “a tinge more populist than Trump himself,” Doolittle said, lauding Vance’s record of working across the aisle with progressive Sen. Elizabeth Warren to crack down on Big Banks.

Doolittle was glad to see the Teamsters president Sean O’Brien speak at the RNC. He thinks Vance can get the union to a Republican endorsement in 2028. “We are on the cusp of gaining labor, and they’re on the cusp of losing it,” he said. “You can’t be America First if you’re not standing with the workers who built the country and are building the country.”

Democrats seem to have forgotten the simple art of showing up, allowing Republicans to move right in. “I’m here today to stand in solidarity with these workers in the fight to keep these jobs here,” said Dave McCormick, a Republican who has since ousted three-term Democratic incumbent Sen. Bob Casey. The workers were protesting the private equity shutdown of a glass factory that makes Pyrex glassware and has buttressed the local economy of Charleroi since 1892. A wall of signs formed behind him that read “KEEP MAKING PYREX IN CHARLEROI” with his own campaign signs peeking through: “BOB STAYS, PA PAYS.”

McCormick, who is worth at least $100 million, was once the CEO of the world’s largest hedge fund, Bridgewater Associates, and owns a mansion in Connecticut. But he also was the first person to offer to come to Charleroi, and that meant something. Erin Guzik worried how she’d raise her child if her boyfriend lost his job at the plant. The green-haired former Green Party voter was undecided but leaning toward McCormick, since he showed up when none of the Democratic senators answered her calls. She said of Casey, “I can’t name one thing that he’s done that’s helped me.”

That could be the lesson for the Democratic Party in 2024, and Charleroi exemplified it in so many ways. “This is the land that time forgot,” Robert Lisovich, 41, told me about the string of industrial towns along the Monongahela River. The titanium worker had just stopped into the local Dairy Queen to pick up a cake for his six-year-old daughter’s birthday.

Like many towns in the Mon Valley, Charleroi “was a polluters paradise. But it had industry, it had jobs,” Lisovich reminisced. Then came the 1980s, and Charleroi never recovered. Lisovich said his dad, a laborer, had to work two or three jobs after the steel mills shut down, but it was never enough to get by. Lisovich’s mother sometimes had to use tea towels on him instead of diapers. People fled Charleroi as economic depression set in.

Washington County flipped red in 2008, after going Democratic since 1932, and then took on a deeper shade with Trump. For years residents voted blue and waited for economic rescue, but people lost faith, Lisovich explained. Biden’s efforts to reindustrialize America with bridges and semiconductors didn’t get through to industrial workers in the Mon Valley, according to Lisovich. They either didn’t know what he did, didn’t see projects come to their communities, or blamed him for climate regulations and wasteful woke spending. Biden’s industrial investments were too little, too late—or, as they say in Pennsylvania, “patch and pray.”

Lisovich started to laugh. He pulled out his iPhone to play a music video of the U2/Green Day cover “The Saints Are Coming,” which satirizes the slow response to Hurricane Katrina’s devastation of New Orleans. Pausing the video with his titanium-speckled fingers, Lisovich pointed out computer-generated helicopters and jets delivering aid to people rushing the Superdome, known as the “shelter of last resort.” A fake TV news banner read “U.S. IRAQ TROOPS REDEPLOYED TO NEW ORLEANS.” Lisovich’s punk-infused point was this help never came, could never come. The government would rather fight a war in the Middle East than save its people from natural disasters. And aid was so slow to arrive that many felt like it never came at all—much the way Lisovich and others became cynical about the promises of the Democratic Party. Decades of deindustrialization wiped away any hope that clung people to the party. Biden’s save-the-day industrial policy was so unbelievable it might as well have been computer-generated. It was a joke.

And Trump was the punchline. “Sooner or later they’re going to stop believing you and believe someone else’s bullshit,” Lisovich said, meaning Trump. The billionaire real estate mogul was better at targeting left-behind areas, he said. Trump first named Charleroi during a September speech in Arizona. “Charleroi, what a beautiful name, but it’s not so beautiful now,” Trump said, painting a misleading picture of the town as besieged by Haitian immigrants. Though Lisovich thought Trump was wrong to scapegoat the Haitians, he welcomed the presidential spotlight, which he hoped would bring investment and change. “Trump was right. This area was beautiful, but in the ’30s, ’40s, ’50s,” said Lisovich.

Disenchantment with Democrats is connected to disenchantment with unions. The United Steelworkers (USW) are a case in point. “The International has lost touch with the members,” said Jason Zugai, vice president of USW Local 2227 at Irvin Works in the Mon Valley. The USW endorsed Biden in 2020 and again in 2024. When he dropped out in July, they endorsed Harris the next day, citing her tie-breaking vote in rescuing 1.2 million union pensions. But to Zugai, “they support Democrats no matter what.” He has seen union workers drift right as manufacturing jobs have disappeared. “If we don’t have jobs, these benefits are irrelevant,” Zugai explained.

The drift from the Democrats is generational. As I sipped beers with steelworkers at a bar across the street from U.S. Steel’s Edgar Thompson Steel Works, I learned that the younger guys voted Republican while the older guys—who spent years with the union and were told to vote Democrat—one by one flipped red with Trump. While they appreciated Biden’s industrial policy, concerns over inflation and wasteful spending came first. They complained about aid flowing to Ukraine instead of their rusting factories. If I mentioned how the Democratic Party, especially under “Union Joe,” had pushed for union benefits and wages, they said protecting their jobs was their first priority. “Green New Deal and all that, their policies are bad for the steelworker,” said Richard Tikey, vice president of USW Local 1557. “Steelworkers didn’t leave the Democrats. Democrats left the steelworkers.”

The union was the institution that once tied steelworkers to the Democratic Party, and people were losing faith in it. “A lot of people feel misrepresented,” said Tikey. For example, USW International President Dave McCall vocally opposed Nippon Steel’s takeover of U.S. Steel, but many rank-and-file members supported the deal on the grounds that Nippon’s $2.7 billion investment would actually save the last of the steel jobs in the Mon Valley. Many members “want to get rid of McCall” and decertify from the union, Tikey said. “Do I support McCall? I can’t honestly say I support him,” Tikey admitted.

A new hire who just lost his job at the closing glass factory in Charleroi asked Tikey what was going to happen to his job now that Biden had blocked the Nippon deal. “Hang in there. We’re going through a hurricane,” Tikey told him.

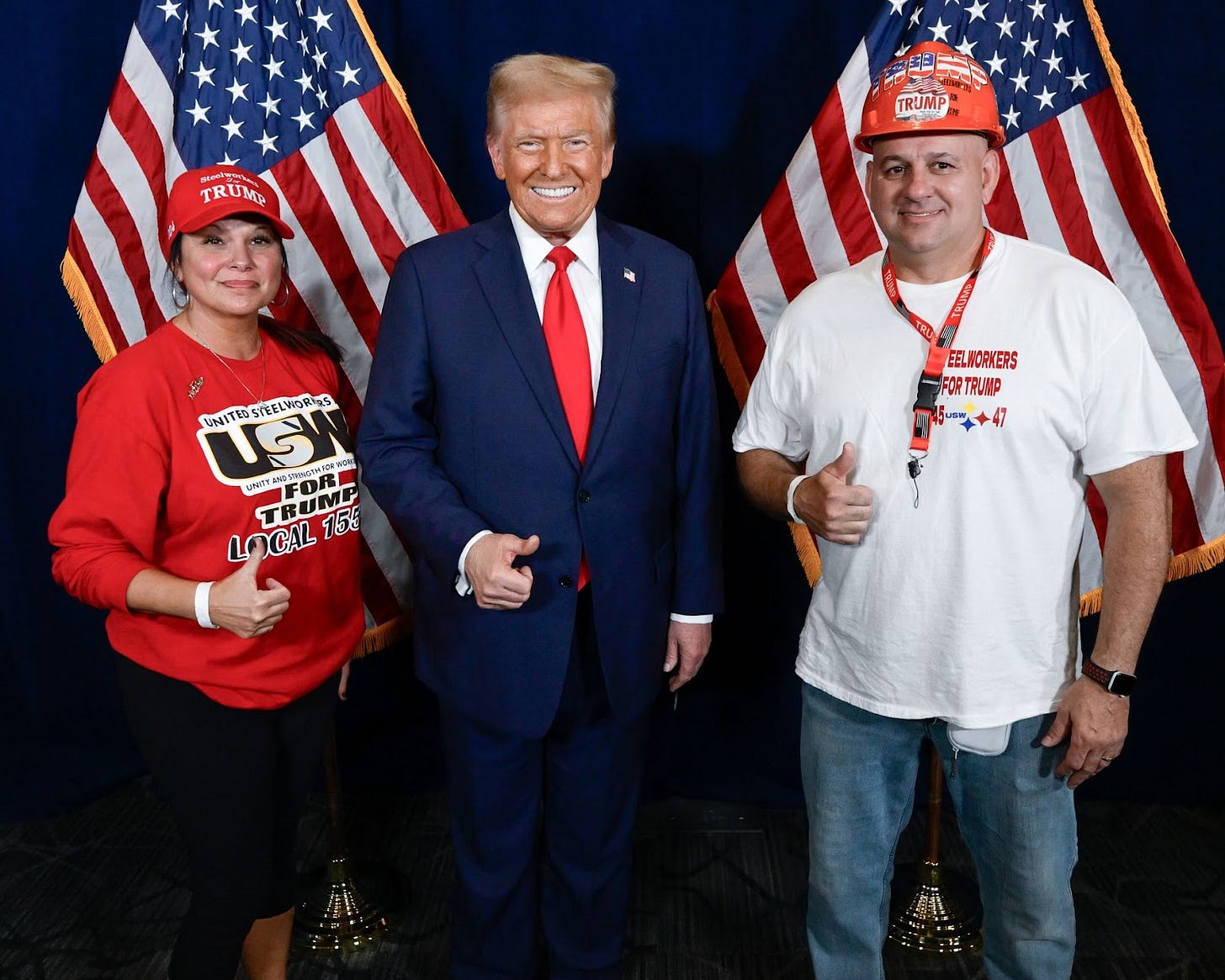

After Trump was shot in Butler, Brian Pavlack, a powerhouse operator at U.S. Steel’s Clairton Works, had enough. He started the Facebook page “Steelworkers for Trump” to “get it out there” that most steelworkers in the Mon Valley supported the once and future president. By November, the group had 2,000 members. With local union leaders by his side, Pavlack organized hundreds of steelworkers to rally with Trump in Latrobe, where Zugai publicly endorsed Trump on behalf of the rank-and-file, defying the Democratic endorsements of USW President McCall. “He thinks he speaks for all of us, and ultimately he doesn’t,” Zugai said.

Zugai wants the USW to either stop endorsing presidential candidates or to poll members, like the Teamsters do. For the first time in nearly three decades, the Teamsters declined to endorse the Democratic candidate for president after members voted to endorse Biden over Trump and then Trump over Harris. Sean O’Brien, at 53 the youngest president in Teamsters history, railed against corporate power at the Republican National Convention. “Sean O’Brien is revolutionizing the way we do things,” said Bill Hamilton, president of the Pennsylvania Teamsters, praising workplace democracy in action, even though he endorsed Harris.

Ron Kaszak, a retired steelworker in northwest Indiana, is the founder of “Republican Steelworkers PAC,” a political action committee. His troubles started in 2020 when he put up four billboards that read “Steelworkers of NW Indiana for Trump” in his blue congressional district. The USW went to the local press and accused the billboards of deceiving the community, and sent out letters to their members and retirees making clear that the union had endorsed Biden. Fearing physical intimidation at work and possible legal action over the word “steelworkers”—which he couldn’t afford—Kaszak changed the billboards to read “Blue Collar Workers of NW Indiana for Trump.”

This time around, now retired and educated on PACs, Kaszak raised $10,000 to spend on stickers, t-shirts, and fourteen billboards across Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, and Pennsylvania. “People are really intimidated to show their support of the Republican Party at work because of retaliation from the union or their coworkers,” he said. “I want to give steelworkers an option to rally around. If they’re not feeling represented by the United Steelworkers and are feeling ostracized because the USW wants to be Democrats, do or die, they shouldn’t have to hide in the closet. They shouldn’t have to be intimidated and scared.”

In theory, Trump’s victory could mean the end of these fledgling institutions. “Trump’s in. What else is there to do for the guy? It will probably fade out,” Tikey said of “Steelworkers for Trump.” But these steelworkers want more than to win an election. They want to feel represented, and they’re making their own spaces for it. Pavlack is considering starting his own PAC and creating a board of Republicans to represent the union. He is networking with U.S. Steel workers in Minnesota and Alabama and “Autoworkers for Trump 2024” in Michigan. Pavlack wants to use his group, and perch as an occasional guest on Fox Business, to oppose right-to-work laws, make Republicans more friendly to unions, and persuade Trump to approve the Nippon deal.

In fact, if Trump scuttles the Nippon deal, steelworkers could punish the GOP at the ballot box. “They might be against Trump. Or they might like what he does. We’ll cross that bridge when we get there,” Tikey said, signaling the Trump coalition’s vulnerability. “If there’s no company, what good is Trump’s tariffs, what good is his tax incentives?” said Andy Macey, a steelworker who’s pushed for the deal. The first-time Trump voter is prepared to blame Trump if it fails.

Kaszak considered pulling the plug on his PAC after Trump won, but now he is planning to collect donations for the 2026 midterms “or save it up for Vance.” He, too, wants to push the Republican Party in a more union-friendly direction. He’s adamantly opposed to right-to-work laws, which allow workers to reap union benefits without paying union dues, but he’s tired of dues going towards Democratic campaigns. “You should always pay your union dues. I’m not anti-union, but you can give your PAC money to me,” Kaszak said.

These steelworkers know they don’t sit comfortably with the Republican Party, whose anti-union roots include codifying right-to-work laws. But they see a future in it, and want to make it theirs, which they can no longer say of a Democratic Party they feel has left them behind. These parallel institutions with their endorsements, billboards, and merch provide the visible signs of a collective identity for workers to latch onto and shape a pro-labor Republican Party, one that can perhaps outlast Trump.

But this America First movement is not the New Deal coalition, at least not yet. While industrial workers—the losers of globalization—proudly broadcast their America First politics, college-educated professionals have fared much better—and are much more bashful. “People don’t like the options they have right now,” said a blonde woman in a Canada Goose parka in an affluent suburb called Emerald Fields. She was taking a break from her remote health-care job to walk her dog at the park, the only person outside among the big houses, gusty streets, and Ring doorbell cameras. Many of her neighbors were voting for Trump, she said, but, “nobody talks about it.” Whereas signs, flags, and banners might coat an entire house in a left-behind town, the only signs here were on street corners, no yard claiming them as their own.

A 46-year-old father in manufacturing consulting invited me into his living room. “I’m not a big Trump fan, but…” he said before getting into why he was drawn to the soon-to-be reelected president. Over and over, he would find some issue with the Democratic Party, at one point calling Harris a “DEI hire.” He seemed eager to spill these secrets to someone, as long as he remained anonymous, but still he was embarrassed to wholly admit his support for Trump. “I’m willing to put up with his foul words to get the results,” he explained. Like his Democratic friends quietly voting for Trump, he didn’t want to out himself and risk alienating his neighbors. The “weird” attack showed its power, preventing America First from visibly penetrating suburban respectability.

Tribe is the essence of politics. It is not about facts and figures. It is about vibes and relationships. It is about culture. A party or movement is successful when it becomes so central to your identity that you won’t leave it even when it defies your preferred stand on this or that issue. The Democratic Party had that kind of hold on the working class, but deindustrialization corroded that identity. Now it is a party on the defensive that must learn to stop letting blood or risk surrendering its members to the GOP.

But Republicans must not get complacent. Trump’s conquest of the working class should not be confused with a lasting realignment. For an election does not make a movement. It is just one battle in the war of ideas. There is another war taking place inside the Republican Party where workers, dislodged from the Democrats, see a future. They’ve chosen a successor and are making demands. It just remains whether the GOP will have them. That can only be known after Trump is gone.