The High Cost of Immigrant Welfare

There’s a bigger story behind the Minnesota fraud scandal.

The unfolding Minnesota scandal in which Somali immigrants defrauded social services of billions of dollars has received a lot of attention, but it points to an even larger issue surrounding immigrants and the social safety net: the high percentage who use our welfare system legally.

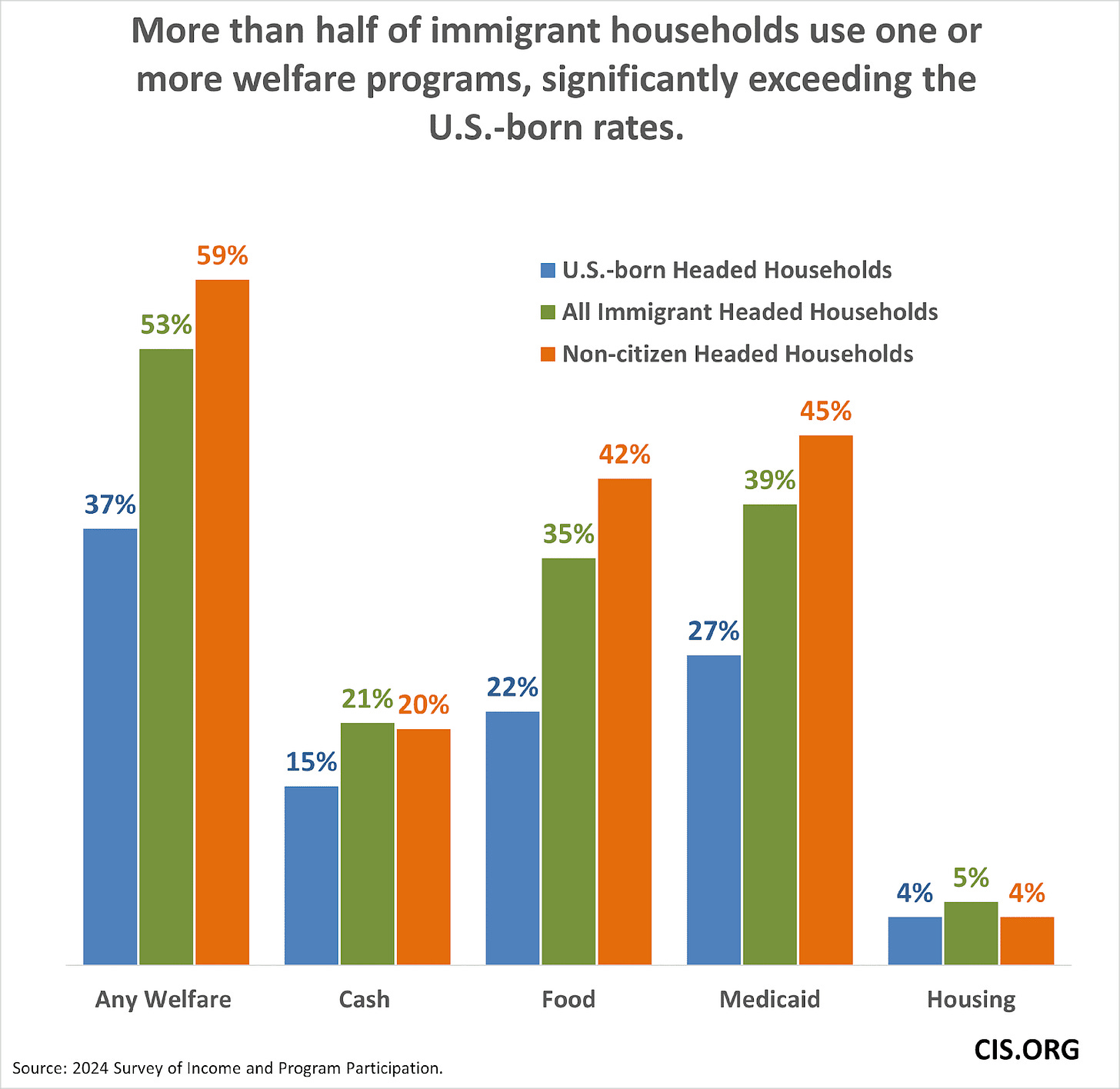

Analysis of the U.S. government’s Survey of Income and Program Participation shows that more than half of immigrant-headed households use at least one welfare program today. The reason is simply that a large share of immigrants have modest levels of education, and their resulting low incomes allow them to qualify for aid.

As the Minnesota welfare scandal highlighted, there are vast amounts of American taxpayer dollars involved, a limited resource that should be spent prudently. By their consumption of scarce public resources, immigrants make it more difficult to assist the poor who were born here, which raises key questions about immigration’s impact on the U.S. labor market and especially on blue collar workers.

There is a common misconception that welfare mainly consists of cash payments to those who do not work. But in fact, most welfare programs are in-kind transfers such as Medicaid, food assistance, or public housing. Working does not prevent someone or their dependents from accessing most of those programs, including some of the cash programs. What matters is income, their number of dependents, and sometimes assets, not employment itself.

The U.S. Census Bureau defines “social welfare programs” as those “based on a low income means-tested eligibility criteria.” Examples cited by the bureau include Supplemental Security Income (SSI), Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF), Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP, sometimes called food stamps), and the Women, Infants, and Children program (WIC). To these can be added public or subsidized housing, free- and reduced-price school meals, and Medicaid. There is also the “refundable” portion of the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), which provides cash payments to workers who pay no federal income tax.

Source: Center for Immigration Studies

Most new legal immigrants, as well as illegal immigrants, are barred from using most welfare programs. However, for several reasons these restrictions have only a modest impact on welfare use by immigrant households.

For one, immigrants, even including illegal immigrants, can receive benefits on behalf of U.S.-born children. Second, the restriction does not apply to all programs, including WIC and school meals, nor does it apply to non-citizen children in some cases.

Some states also provide their own welfare services to otherwise ineligible immigrants, and several million illegal immigrants have obtained work authorization or Social Security numbers (e.g. DACA, Temporary Protected Status, and many parolees) allowing receipt of the EITC. Naturalized green card holders gain full welfare eligibility, and many legal immigrants have lived here long enough to qualify for welfare even without naturalizing. Collectively, this means that millions of immigrants receive support from the U.S. taxpayer.

The 2024 SIPP shows that 53% of all immigrant households use one or more welfare programs, compared to 37% of U.S.-born households. Based on this data, my best estimate is that 51% of households headed by legal immigrants and 61% of households headed by illegal immigrants use at least one major welfare program. Compared to U.S.-born households, those headed by immigrants make especially heavy use of food programs, Medicaid, and the EITC.

If one assumes that immigration is supposed to benefit the United States, such high welfare use by immigrants is extremely problematic.

The federal government spends roughly $1 trillion per year on welfare, and states spend another $300 billion a year on Medicaid alone. High welfare use makes it likely that immigrants are a net fiscal drain, both because of direct costs and because those accessing means-tested programs typically pay little to no federal or state income tax. This assistance should go toward helping the needy and low-income already here.

It is important to point out that immigrants’ use of welfare is not caused by an unwillingness to work. In fact, immigrant households are more likely to have a worker present than U.S.-born households (who are more likely to include retirees). However, 53% of immigrant households with at least one worker access the welfare system, compared to 38% of working native households.

Here too, the impact of immigrant workers on the native-born population is likely to be a net negative. An increased supply of labor, especially at the low end of the market, will put downward pressure on wages, keeping more employees of all kinds on assistance programs. Employers lobby heavily for more foreign labor, but they overlook the welfare costs those workers and their families create because such costs are diffuse—borne by all taxpayers.

The key policy question is whether we should continue to allow in large numbers of less-educated foreign workers when stemming the flow could cause wages to rise, drawing less-educated U.S.-born men back into the labor force and off of federal assistance.

Working on Welfare

Immigration advocates attempt several responses to this data. The first is to simply ignore it and claim that eligibility restrictions prevent immigrants from using welfare programs. Second, the Cato Institute and others argue that Social Security and Medicare should be included in welfare use rates, though somewhat amusingly, Cato’s own Poverty and Welfare Handbook explicitly excludes those programs because they are “more universal.” The Census Bureau correctly calls these programs “social insurance” and considers them distinct from welfare because one has to pay into them to receive benefits.

Another argument is that low-income immigrants are no more likely to use welfare than low-income natives. This is true for some programs, but not others. But more importantly, immigrants are significantly more likely to be low-income than natives. The poverty rate for immigrant households in the 2024 SIPP was 41% higher than for U.S.-born households.

Some immigration boosters further assert that if the U.S.-born dependent children of immigrant parents receive WIC, food stamps, Medicaid, or any other benefit, such benefits should be attributed to natives instead of immigrants. Using this approach, Cato argues in a recent report that immigrants’ use of welfare is not all that high and that they are actually a net fiscal benefit. In order to believe that result, one would also have to believe that when immigrants come to America and have children whom they are unable to support, and then turn to the welfare system for support, the resulting costs have nothing to do with immigration.

Assuming away the enormous cost of providing welfare to the dependent children of immigrants ignores the obvious fact that immigrants benefit directly when the government provides food, funding, housing, or medical care to their children. Those welfare costs would not exist if their parents had not been allowed into the country. Additionally, 37% of childless immigrant households access one or more welfare programs compared to 29% of childless U.S.-born households. Children are not the only reason that immigrant welfare use is high.

A 2017 National Academy of Sciences study ran eight different fiscal scenarios looking at all the costs versus all the tax payments immigrants and their descendants might make over 75 years—with four coming out negative and four positive. Those results are not only ambiguous, they’re extremely speculative, requiring assumptions about the future economic mobility of generations not yet born, along with predicting future tax rates and spending. At present, the NAS study found that immigrants were a net drain, with welfare being a big reason why.

The primary reason for heavy welfare use among immigrants is their relatively modest levels of education and resulting low incomes compared to American citizens. Of households headed by an immigrant without a bachelor’s degree, 68% access the welfare system, compared to 34% for those headed by an immigrant with a college education. Education makes a huge difference, but only about one-fifth of legal permanent immigrants were admitted because of their education or skills. Illegal immigrants of course are not selected for their education at all.

One might argue that we could bring in large numbers of less-educated immigrant workers without burdening the welfare system if we just had more laws and rules to prevent them from accessing it. However, the heavy use of welfare by existing illegal immigrant households shows this is not likely to work. Moreover, it is difficult to imagine Americans denying things like medical care and food programs to low-income immigrants and their children once here.

Many immigrants come to America to work, but struggle to support themselves or their children once they arrive and turn to taxpayers. As a result, heavy immigrant use of welfare not only creates significant fiscal costs, it strains the social safety net, reducing the funds that might otherwise go to the poor who are already here.

When presented with this information, many Americans are fond of pointing out that their immigrant ancestors did not use welfare. But the truth is that these programs didn’t even exist 100 years ago. Looking forward, we need to ensure that our immigration system reflects the realities of the modern American labor market and the existence of the welfare state.

If we want immigration to avoid burdening the public fisc in the future, then moving to a system that selects legal immigrants for their education and likely earning power, coupled with robust immigration enforcement, would significantly reduce the size and scale of this problem in the future.

" Second, the Cato Institute and others argue that Social Security and Medicare should be included in welfare use rates, though somewhat amusingly, Cato’s own Poverty and Welfare Handbook explicitly excludes those programs because they are “more universal.” The Census Bureau correctly calls these programs “social insurance” and considers them distinct from welfare because one has to pay into them to receive benefits."

This strikes me as pretty misleading. What matters isn’t how the Census Bureau classifies programs for purposes of welfare-use statistics, but whether immigrants are a net fiscal burden relative to native-born citizens. For that question, excluding the two largest components of the modern welfare state—Social Security and Medicare—because they don’t meet a technical definition of “welfare,” and are instead labeled “social insurance,” is just a dodge.

It’s true that one must pay into Social Security to receive benefits, but that doesn’t make the program actuarially fair. Its benefit formula is explicitly progressive: lower-income workers receive substantially more in benefits relative to their contributions than higher-income workers do. Medicare is similar in spirit: it is not means-tested, but it is financed in large part through general revenues and provides benefits that have little relation to individual contributions.

If the question is whether immigrants impose a net fiscal cost, then what matters is taxes paid versus benefits received over the lifetime—not whether those benefits are classified as “welfare” or “social insurance.”

Another thought is that those taxpayer dollars going to working immigrants are actually subsidizing their employers, who would otherwise be forced to pay higher wages if they hoped to fill available jobs. Especially since many of those jobs are not readily subject to automation.