The ‘Realignment’ Shouldn’t Mean Medicaid Cuts

The Senate can still protect working-class families in the tax fight.

By Patrick T. Brown, fellow at the Ethics and Public Policy Center.

Speaker Mike Johnson successfully walked the tightrope yet again, and now the Senate faces the “One, Big, Beautiful” task of getting the Republican reconciliation bill across the finish line.

The bill is a Republican wish list, with the potential to give each of the various factions on the right something to cheer for. It includes everything from school choice to border security to increased endowment taxes to defunding Planned Parenthood to lots and lots of (unpaid for) tax cuts. Yet their “all of the above” approach to federal policymaking includes some half-baked ideas, particularly when it comes to safety-net policy.

House Republicans were under the gun to find budgetary savings that didn’t involve touching the military or Social Security and Medicare entitlements for seniors. That meant that most of the budgetary pay-fors in their “One, Big Beautiful Bill” (OBBB) come from cuts to discretionary programs (as well as ending Biden-era spending on climate initiatives and student loans). Limited-government voices seeking to trim domestic health and safety net programs are certainly nothing new, but this year’s takes that impulse and puts it on steroids. In so doing, it hands Democrats a ready-made campaign tactic—“Republicans cut safety net programs so that their rich donors could get a tax cut.”

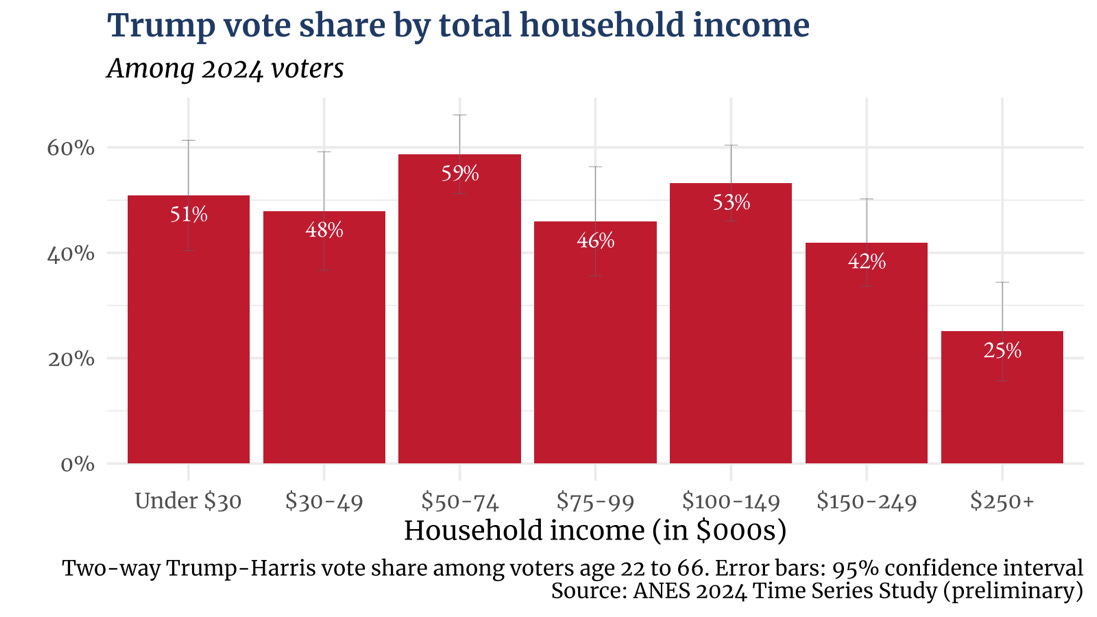

Most fundamentally, the OBBB belies a fundamental misunderstanding of the GOP’s new political base. As the parties have realigned along educational lines, rather than race or religion, non-college voters, who support President Trump, are more likely to benefit from the programs that Republicans want to slash. My analysis of preliminary 2024 survey data suggests voters making below $50,000 were more likely to vote for President Trump than those making over $150,000, and the New York Times also finds areas with lower incomes were more likely to have shifted right in 2024. Slashing, rather than productively reforming, health care programs that serve moderate-income Americans would be a very odd way to repay them for their support in 2024.

The biggest source of cuts—and the one that has gotten the most media attention—is changes to the Medicaid program that covers health care costs for low-income Americans. The longest-lasting legacy of President Obama’s Affordable Care Act is the expansion of Medicaid eligibility to prime-age adults with incomes up to 138% of the federal poverty line (ten states have yet to expand Medicaid to this population.) This has led many Republicans to publicly worry that spending on these adults (age 19 to 64) is crowding out Medicaid spending meant for its initial population, like pregnant women, the disabled and kids, threatening the long-term stability of the program and our nation’s finances.

This is somewhat of a red herring; the long-term pressures on our fiscal picture are being driven by old-age entitlements and an aging population, not spending on programs like Medicaid. Some of these cuts are easy targets. Restricting illegal immigrants’ ability to access to safety-net benefits is certainly politically popular, even if that’s not a huge source of federal spending. There is some gamesmanship in how states collect federal reimbursement that is an appropriate target for which Republican lawmakers to take aim.

Unfortunately, they seem interested in going beyond tighter administrative purse strings to steps that would actively take health coverage away from low-income Americans. The “One, Big, Beautiful Bill” would attach work requirements to Medicaid, starting in December 2026, which is a policy that sells well in theory—who would oppose the idea that people should show evidence they are trying to contribute to society in exchange for receiving safety-net benefits? Unfortunately, when it comes to contact with reality, the idea fizzles.

In arguing for Medicaid work requirements for able-bodied adults without dependents, Rep. Jimmy Patronis (R-FL) typified the GOP approach in an interview on CNN: “The able-bodied person I’m talking about is the 25-year-old who is sitting on his couch playing Xbox.” But let’s think through his example—Medicaid reimburses for medical care. It does not increase your take-home pay or put food on your table. So a healthy 25-year-old male is unlikely to see much benefit from Medicaid unless he has a severe health incident. In a serious health situation, cutting him off from Medicaid coverage means the hospital now has to treat him without getting reimbursed.

As the Heritage Foundation’s Robert Rector, an anti-welfare stalwart, wrote in 2017, “The work requirement would reduce Medicaid enrollments, but Medicaid costs might well go up because the eligible ABAWDs would go to the emergency room rather than receive routine care elsewhere.” And when states tried requiring work in exchange for Medicaid eligibility, the resulting drop in case loads was predominantly driven by otherwise-eligible individuals failing to successfully navigate the eligibility process, rather than an increase in employment or culling ineligible applications. OBBB presumes it can find savings from rolling out nationwide work requirements for Medicaid in just a couple of years. In practice, that will mean using the savings from eligible families failing to complete the requisite paperwork to pay for tax breaks elsewhere. It’s bad policy design and foolhardy politics for a coalition of the working class.

And it’s not just in health care coverage that the impulse to reform welfare is leading Republicans astray. Rather than supporting marriage for low- and middle-income households, the design of their temporary expansion of the standard deduction actually worsens marriage penalties.

While the bill includes a laudable and politically popular expansion of the overall value of the Child Tax Credit (CTC) from $2,000 to $2,500 per child, House Republicans couldn’t come to an agreement on expanding support for the roughly 17 million children who live in households whose earnings fall below the threshold needed to receive the full value of the CTC. At the same time, a new requirement with the laudable goal of reducing incorrect claims in the Earned Income Tax Credit could result in more complexity for low- and middle-income earners. That should make boosting the CTC for moderate-income working families more, rather than less, important.

There is always room to improve the way America provides benefits to low-income individuals and households. First and foremost, we could prioritize smoothing cliffs that penalize low-wage workers for getting a promotion or working longer hours, and eliminate policies that effectively subsidize cohabitation over marriage. We could encourage more states to experiment with “one door” approaches to in-person social services. The bill appropriately tackles the budgetary gamesmanship that inflates costs for the federal government without improving health outcomes for low-income individuals.

Unfortunately, by looking at safety-net programs primarily as sources of budget savings, rather than thinking about how they can improve the way they deliver much-needed services and help get Americans out of poverty, the GOP is painting itself into an unpopular corner.

The Congressional Budget Office finds that resources would decline for the lowest-income households and increase for those in the highest income brackets. If the Democrats run campaign ads accusing the GOP of taking away health care benefits to fund tax cuts, Republicans will cry foul. Yet that is where their current legislative trajectory is taking them. In this, President Trump’s political instincts are spot-on, reportedly telling Sen. Josh Hawley that politicians who cut Medicaid are “stupid” and “lose elections.” If Republicans want to avoid midterm accusations of running a reverse Robin Hood operation, they still have time to alter the legislation to better protect working-class families—even if it comes at the expense of quite so many tax cuts.

I predict that states will find a way to get people Medicaid anyway and that it’s just a CBO gimmick to get the tax cuts through.