You may have noticed you’re receiving your roundup on Monday instead of Friday. That’s because we’re doing some remodeling, which I’d like to tell you about before diving in:

1. U/A + Commonplace: better together! We’re combining Understanding America with the broader Commonplace magazine, all of which will now come to your inbox via Substack. I’ll still be writing the weekly roundup, on Mondays instead of Fridays. The weekly essays you’ve received on Mondays will arrive roughly every other week, as Commonplace essays.

2. What Emails You’ll Receive: 3 instead of 2. Therefore, we are also merging the Understanding America and Commonplace mailing lists. So if in the past you’ve only been receiving my two weekly U/A emails, you should now expect to receive three weekly emails: Something on Thursday from Commonplace and something on Saturday from Commonplace (these will include my regular writing), and then U/A on Monday from me. Other new pieces, as well as the podcast, will also go up at commonplace.org (where the Substack will live) throughout the week.

Note: On the Commonplace website and in the emails, you’ll be able to subscribe or unsubscribe with the click of a button if you only want to receive Commonplace articles, or only the weekly U/A. You will also be able to subscribe to the American Compass Podcast if you want to receive that in your inbox on Fridays.

3. Subscriptions: still free. We’ve never charged for U/A or Commonplace and we’re not starting now. The “paid subscription” option offers an opportunity to make a donation to American Compass, helping to support all this work, and that will remain the case. If you are an active paid subscriber to U/A, congratulations, you are now an active paid subscriber to Commonplace, featuring U/A. If you have not previously made a donation to American Compass, but enjoy U/A and wish to support its continued existence, now would be a great time to become a paid subscriber!

4. Please Excuse Our Appearance… Merging two active sites from two platforms into a single active site is a somewhat messy process so, between now and Thursday, U/A and Commonplace may be in various states of disrepair. Apologies for that! We will strive not to hit you accidentally with an incorrectly formatted email and so on, but you never know… your patience is appreciated and everything should be squared away and running smoothly by the end of the week.

Enough about me. Your one thing to read this week is, well, a listen, and… oh, shoot, it’s me again. But I really want to recommend listening to Friday’s American Compass Podcast episode with Simon Johnson, professor at MIT and most recent recipient of the Nobel Prize in economics. Professor Johnson and I discuss the issues surrounding federal funding of scientific research, recent cuts by the Trump administration, and what reforms might make sense.

What’s most interesting, I think, and the reason for the recommendation, is that we spend a lot of time talking about whether the nation is best served by concentrating funding at a fairly narrow set of prestigious institutions or whether we should reduce that funding substantially and redirect it to a broader set of institutions in a broader set of places. My oversimplified proposal is to cap federal funding by zip code. Scientists can all congregate at MIT and Harvard if they want, but only so much funding goes to just-outside-Boston. Their labs will have much greater chance of success if they relocate to Case Western in Cleveland or the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque. Professor Johnson says he likes this idea a lot:

The reason I like it is I feel it fits with American history. If you look at how the country industrialized—without federal money, by the way, federal money coming to science is a recent thing, as we already mentioned. So if you look at the late 19th century, early 20th century, what actually happened was people had breakthroughs in particular technologies, or they were good at something, in a certain place.

I happen to know a little bit about Northwestern Ohio and what happened in Toledo. And so there, there was some cheap gas, some glass industry moved there. Then some other people came who were very interested in using glass. Then they became really good at innovations that were glass related. Then they started producing machines that made glass models that they sold to the world, right? So there was this natural agglomeration effect, and if you wanted to be in glass, and I think a lot of the glass related to the auto industry as well, then that was the place to go. So the talent was pulled towards a particular sector.

Now, nobody gave Toledo a monopoly on glass. Nobody said other people couldn't do glass. Obviously not. Lots of competition. But the idea that people are pulled towards particular places where it is happening, that's where the action is, that's where you've got to be—I think that's a very natural process.

Now, after World War II, much more innovation is coming from science, much more is being driven by federal government money, and therefore much more is politically allocated. I don't mean partisan politically. I mean, there's a decision in an agency that we should go with this. And I do think, to be fair to the agencies, a lot of times they're under pressure from Congress to get me that agglomeration effect. I want a bigger bang for my buck, right? Why are you giving it to this place that has no record or reputation when you could give it to MIT? And I think the answer that you're providing, the answer I'm providing, is well, if you give enough money, offer a new initiative to a different place, and you build it, they will come. The scientists will go there because they will move for the labs.

Now, you have to think about are we doing a single source supplier? Are we having competition in this? You know, letting people get monopoly rights over things the government does is never a good idea. But spreading the money around the country I think is brilliant. I think it's absolutely needed and I think a lot of the dissatisfaction we're getting with science, a lot of the view that science is “elite,” actually comes from the fact that the geography—not for bad reasons, not because it was corrupt or anything, but just because the money followed the money and it followed where the talent already was. That has come to favor just a few places, mostly on the East and West Coasts, and that's not sustainable politically.

We discuss how exactly this might work. Johnson makes the good point that in a lot of cases you might have leading institutions open new labs in different places. Besides the fact that the “M” in MIT stands for Massachusetts, is there any reason that all of MIT should be in one town? Large private-sector firms don’t do that. Prestigious universities had no trouble lending their brands and faculty to Middle Eastern petrostates offering sufficient cash. Presumably they would be open to reaching new populations within their own country too.

One broader lesson here is substantive, and regards the unwise obsession that economists have had with “agglomeration”—the idea that it is more “efficient” to concentrate talent and investment in narrow geographies where it can be most productive. The logic of agglomeration extends along only one margin. Putting the tenth advanced biochemistry laboratory next to the first nine in Cambridge may indeed make it some amount more productive than putting it in St. Louis. But when it comes to the economic vitality of Cambridge, putting it there has essentially no effect, while St. Louis might reap enormous benefits. Good science policy, which sells itself as not only generating patents, but also spreading prosperity broadly, creating good jobs, and so on, needs to consider these other margins.

In the long run, the implications for science are more complicated too: a scientific community spread across the country, drawing in talent broadly, with stiff competition between a wide range of institutions and the private sector firms they spawn, may indeed be far more innovative than a community consolidated in just a few cities. In this sense the issue is similar to that in antitrust: will the aerospace industry be most innovative if all the top engineers work together at Boeing and can benefit from the scale of its engineering operation? Probably not.

The other broader lesson is a political one. The Trump administration has many legitimate reasons for confronting the excesses and dysfunction of higher education, in elite institutions especially. But if the goal is to build support for an alternative course, the right way to slash funding is to redirect it to better uses. In this instance, sharply cutting funding to these institutions could be wildly popular, easily defended, and productive, too, if it were designed as primarily a reallocation to new ways of funding science in new places. Likewise, sharp cuts to other forms of funding, ending student loan subsidies, and so on would make much more sense if paired with expansion of non-college pathways that would better serve most Americans.

In taking on elite higher education, Trump has chosen a much needed fight. But winning that fight in the public square, and strengthening America in the process, requires not just knowing what to tear down but also what to build up.

WHAT ELSE SHOULD YOU BE READING?

Economics Teaching Has Become the Aeroflot of Ideas | Ha-Joon Chang, Financial Times

It’s not every day an economics says something more contemptuous of economics than I can offer, but “Aeroflot of Ideas” is pretty good. Chang writes, “Economics today resembles Catholic theology in medieval Europe: a rigid doctrine guarded by a modern priesthood who claim to possess the sole truth. Dissenters are shunned. Non-economists are told to ‘think like an economist’ or not think at all. This is not education. It’s indoctrination.”

Bonus link: In one of my favorite pieces we’ve ever published at American Compass, “Marginal Prophets,” Matthew Walther extends much further the analogy of economics to magical thinking.

Factories Were Pushed Out of Cities. Their Return Could Revive Downtowns. | Linda Baker, New York Times

This is a cool trend, and a nice reminder that “the return of manufacturing is not going to look like the jobs that disappeared” is a feature, not a bug of reindustrialization. From robotics to AI to 3D printing to electrification, the way we make things in the future should be very different than the way we made them in the past. But first we have to decide we want to make them at all.

Lawmakers Subpoena JPMorgan and BofA Over IPO of Chinese Battery Giant | Corrie Driebusch and Rebecca Feng, Wall Street Journal

Priceless quote here from Jaime Dimon, defending his bank’s work with a company entangled in the Chinese Communist Party’s military activities: “If we thought it was wrong, we wouldn’t do it.” Unless there’s another Jamie Dimon who recently headed JPMorgan, this is the same one who apologized a few years ago for making a joke about the CCP by saying, “it’s never right to joke about or denigrate any group of people, whether it’s a country, its leadership, or any part of a society and culture.” Seems likely that if he thinks it’s wrong, but also good for business, he will do it. Which is why we need not only legal remedies, but also social ones. Let’s have Dimon testify for an hour or two under oath about JP Morgan’s business in China. It would be very interesting.

Was Online Sports Gambling a Mistake? | Kite & Key Media

Kite & Key does excellent work and this short video is the definitive primer on the terrible policy mistake of legalizing sports gambling and the “uncomfortable truth” that “this is a business model that depends on addiction.”

Bonus link: John Arnold had an excellent thread highlighting some awful survey data (25% of Americans who have placed a bet in the past 6 months say they have been unable to pay a bill because of gambling) and making an especially tough point: “Gambling addiction is a slow and quiet killer. You know if someone close to you drinks too much. You don't know if they have a gambling problem.”

Project Vend: Can Claude Run a Small Shop? | Anthropic

Sorry I missed this when it came out last month. Anthropic ran a test of its “Claude” large language model, assigning it to run a small convenience store for employees. The results are undoubtedly hilarious, but more importantly they’re something of a Rorschach Test. The from Claude’s miserable failures, according to the company, is that with “additional scaffolding—that is, more careful prompts, easier-to-use business tools,” it could very well succeed: “We think this experiment suggests that AI middle-managers are plausibly on the horizon.” The story to me reads like a content mimic incapable of anything vaguely resembling thought producing pretty much what you’d expect.

I also cannot help but detect a shifting of goalposts, with Anthropic defining “AI middle manager” as a situation where people are “instructed about what to order and stock by an AI system.” A computer system making decisions about what to order and stock is not an “AI middle manager,” it’s an inventory management system. Those have existed for decades. Will AI make them more effective? Sure, probably. Yay. Shrug.

TARIFF CORNER

How the EU Succumbed to Trump’s Tariff Steamroller | Andy Bounds et al, Financial Times

While it remains to be seen exactly how deals with the EU and Japan settle, the Trump administration appears close to landing agreements with most major U.S. trading partners (ex. China) in advance of its August 1 deadline, establishing a new framework for international trade among U.S.-aligned economies comprising the majority of global GDP. The EU capitulation has been particularly dramatic, as the FT notes: “There is no hiding the fact the EU was rolled over by the Trump juggernaut, said one ambassador. ‘Trump worked out exactly where our pain threshold is.’” The EU had previously attempted to hold the line on WTO principles, for itself and others, but that appears to be out the window forever.

When Are Tariffs Optimal? | Thomas A. Lubik, Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond

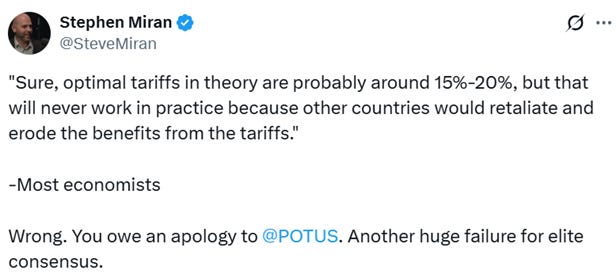

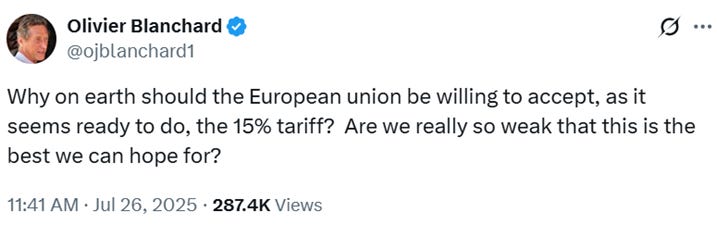

And with most trading partners accepting deals in which the U.S. levies tariffs but they do not, get ready to hear a lot more about “optimal tariff theory.” Economists, you may recall, have been quite eager to lecture that levying tariffs will simply prompt retaliation, leaving everyone worse off. But… what if that’s not what happens? Especially seeing as it hasn’t. In fact, if other countries do not retaliate, there’s a good case that tariffs in the 15% range are indeed optimal. Siri, in what range is the United States landing with its one-sided tariffs against which countries are agreeing not to retaliate?

In the announcement of the EU deal, especially, one detects a frustration that the Trump team actually understood that the strategy in the best interests of the United States was not the same strategy that had been sold by the economists as best for everyone.

Of course, economists have always known that free trade is not necessarily in the best interests of the United States, because that is the unavoidable conclusion of doing actual economics. As Paul Samuelson wrote in his seminal Economics textbook: “Any intelligent person who agrees that the United States must play an important role in the postwar international world will strongly oppose [protectionist] policies, because they all attempt to snatch prosperity for ourselves at the expense of the rest of the world.” The case was one for placing the global interest over the American interest, and that era is over.

A Game-Changing Industrial Policy Tool Buried in OBBBA | Michael McNair, X

McNair notes Congress appears to have created accounting rules for the new Department of Defense Credit Program Account in the Office of Strategic Capital that will convert its $1.5B appropriation into as much as $200B in lending capacity. Keep an eye on it.

CRINGE CORNER

What a Democrat Could Do With Trump’s Power | Paul Rosenzweig, The Atlantic

I’m sorry, but this is a very funny read. Rosenzweig tries to explain how horrible it would be if a Democrat were to use presidential power the way Trump has, and basically just comes up with a list of things recent Democratic presidents have done without hesitation.

“ICE employees, for instance, might find themselves subject to a reduction in force under a new Democratic administration.”

“Transgender soldiers could be welcomed back into the military, for example. Forts can be renamed… but the prospect of a return of Trumpism down the line will resonate for a long time in terms of substantial losses of expertise, stability, and trust.”

“The president could flip Trump’s agenda on its head—denying federal funding to universities that lack DEI policies.”

“White House Deputy Chief of Staff Stephen Miller, the former Trump adviser Steve Bannon, and others could face the expense of criminal investigation.”

(D.A. Bragg, A.G. James Announce Indictment of Stephen Bannon, Manhattan DA)

“Conservative states such as Alabama and Texas could be investigated for civil-rights violations.”

(Justice Department Is Investigating Texas’ Operation Lone Star for Alleged Civil Rights Violations, Texas Tribune)

(Justice Department Investigating Alleged Civil Rights Violations in Alabama Schools, Equal Justice Initiative)

“And the president could unilaterally issue subpoenas to almost any conservative-supporting institution … even attempt to end the nonprofit status of all religious organizations.”

“One of the most significant assertions of presidential power Trump has made is that he can nullify a law—that is, that he can dispense with enforcing it based on his authority as chief executive.”

(Obama's Policy Strategy: Ignore Laws, Politico)

“The prime example of this is his refusal to enforce the congressionally mandated ban on TikTok.”

“Or, to parallel Trump as much as possible, penalties against favored European enterprises could be waived as part of ‘diplomatic negotiations.’”

The point is not, of course, that any of these things were good when the Democrats did them, or that they are good when a Republican does them, or that in any particular case the considerations on each side are of equivalent weight. The point is that this approach to executive power is not new, and when a writer for The Atlantic laments that, “what lies ahead, then, is a new era of pendulum swings, replacing the stability of the postwar governing consensus,” what he is saying is that it was all fun and games when Democrats did these things, but when Republicans do it in the opposite direction, we have, gasp, instability. A postwar governing consensus built upon only one side using these tools was obviously not going to be a stable one, and so here we are.

Fed Staff Members Cite Tariffs and Inflation for Costly Renovations | Alan Rappeport and Colby Smith, New York Times

Res ipsa loquitur.

AND AT COMMONPLACE

The Novel Is Dead Because James Comey Killed It by Jude Russo. Why don't you write a book about this crime, counsellor?

The Attention Economy by FTC chairman Andrew Ferguson. How Big Tech firms exploit children and hurt families.

Why Assisted Suicide Wins by Nic Rowan. The 'right to die' is quietly being established in the states.

And as I already told you about, Professor Simon Johnson joins me on the American Compass Podcast.

Enjoy the week!

—Oren

On cutting science funding: I’m a Harvard and Caltech grad who has been doing research and teaching at Arizona State University for 21 years. Your suggestion of flowing federal research funding away from a few prestigious institutions is great, except for two things, below.

First, decentralization of funding seems to me to have already been a general trend for the past generation or two. This is anecdotal - I don’t have the data at my fingertips - but it’s how and why I’ve been able to build a first-rate research program at what used to be thought of as a party school - and how such a school has been able to ascend the ranks of high-impact institutions. When I was a grad student, you pretty much had to be at a “prestige” institution to build a first-rate career. That hasn’t been true for a long time. More such decentralization would be great, but this should be understood as “more, please” not a pivot from past practice. (If there are data that prove me wrong, then I’ll withdraw this critique).

Second, and more importantly, what you propose is decidedly not what is happening under this Administration. The proposed cuts to overhead rates damage the entire research enterprise, and in fact hurt hardest those institutions that do not have wealthy alumni who might pick up some of the slack of infrastructure costs - which is to say, non-elite institutions doing research. At ASU, for example, we’ve expanded our labs through bond issues backed by our federal overhead income. At Harvard, large donors can and do help fund the facilities. There’s been no suggestion of which I’m aware to modulate these cuts based on institutional wealth or other “elite” measures. The blunt cuts to NSF, NASA, and so many other agencies similarly are not modulated in any way to spare or buffer the damage beyond the elite institutions. It’s an all-out assault, across the board, harming all research-intensive institutions. The elite institutions can surely keep it up regardless. The rest of us? It’s a dicier proposition, ultimately dependent on the will of state legislatures and governors, and the latitude they give to university leaders to change the ways the universities finance research.

So, great idea, in the category of “if only it were so”. Or rather, “if only the Administration you support wasn’t doing pretty much the opposite”. Instead of talking to an economist, who has never run or worked in a laboratory, talk to someone who knows a thing or two about the realities of research funding and university management outside of elite institutions! Get ASU Pres. Michael Crow… (It is ironic to see you of all people, Oren, ground your thoughts on this topic in the thoughts of an elite economist, as though they are relevant to what’s really going on).

You're assuming that the goal is to make science funding more efficient and effective. I'm not sure that's accurate. It appears to be mostly performative: anti-wokeness and revenge against the libs.

It's rather like Trump's immigration raids. Mandatory e-verify with major fines for hiring illegals and imprisonment for business owners who refused to stop would be far more effective by drying up job opportunities. But people who leave of their own accord don't produce photo ops.

Similarly, there are lots of quiet ways (that would also fight wokeness) to make science funding better. But Trump prefers loud and performative instead of quiet and effective. The P.T. Barnum comparison is accurate.

(Note, I say this as someone who voted for him all 3 times, is glad he won, and supports an America First agenda. I'm just clear-eyed that the success of that agenda is as often in spite of Trump as it is because of him.)

BTW: Ian Fletcher made the optimal tariff argument 25 years ago (when it was very unpopular) in Free Trade Doesn't Work. He doesn't get credit for it, but the Reagan aphorism about credit rather applies here.