Today’s Eugenicists

There is an objective good we should strive for in life. It’s just not found in a lab.

It is a self-evident truth that there is no such thing as an average baby. It is equally true, and not in the slightest bit contradictory, that all babies are average. The quicker we learn to hold both of these truths in tension, the better we will be able to deter the eugenics movement that, 80 years after we saw its full, rotten fruit, continues to haunt us.

The threat is real, and whether it wears grey uniforms with skulls on caps or comes packaged in shiny, attractive, Silicon Valley optimism, the end result is the same. Those who find themselves in positions of wealth and power will determine the nature of “average,” deciding who gets to live and who gets to die. And it’s the poor, the weak, and the outcasts who suffer.

But I’m getting ahead of myself.

Have you ever held a baby? I’m not asking if you’ve ever seen a baby. I’m asking if you’ve ever held an actual little baby that, whether grunting or pooping, squirming or crying, is a person you encounter rather than just an idea.

It’s possible, at first glance, to think that all babies are the same. And in some ways they are: The round heads; the big eyes; the need to eat, sleep, have their diapers changed, and be loved. There are millions of babies born every week around the world, even in our low-fertility era. It’s easy to view them as a mass of humanity, but the fact is that each of those babies is, scientifically, morally, and in the fullest depth of the term, a person, unique in all of history.

As the father of monozygotic (identical) twins, I can tell you that even possessing the exact same genetic material does nothing to change the individuality—the unique anti-averageness—of the two persons who are my sons.

Deadly Orchids

But Noor Siddiqui, the founder of Orchid Inc., doesn’t want average babies. She asks parents, “will you have an average baby or a superbaby?” and her company suggests that, with the help of their (proprietary) genetic screening tools, the “genetic lottery is ending, and a new generation of parenthood is beginning.”

What does that look like?

Orchid offers to pre-screen embryos for a wide range of “genetic defaults” in order to “mitigate risks that could affect a future baby.” Parents then create, via IVF, a number of babies—and yes, scientifically speaking an embryo is a baby—that are scanned for health issues ranging from autism to cancer and type 1 diabetes. Through this process, Orchid says, parents can “find and implant the embryo at lowest risk for a disease.”

The product is marketed as a mixture of harm reduction and competitive advantage, and seems to be targeted at achievement-oriented parents. As one Orchid testimonial reads, “this is the way to reduce disease and suffering in kids, and is the best thing you can do for your child and yourself. The fact that we have screened for so much gives us peace of mind.”

An Orchid customer testimonial (photo credit: Orchid’s website, www.orchidhealth.com)

This plays on both the legitimate fears of most parents (who among us does not want their child to be healthy?) and a type of genetic or social avarice—the desire to have children who, presumably like their parents, will perform best in a competitive world.

Parents are encouraged to “make an informed decision” to “mitigate risks that could affect a future baby” (emphasis added). The process gives participants, aided by a “board-certified genetic counsellor,” the ability to choose which baby lives and which is discarded for being undesirable. I use discarded intentionally, as the process necessarily involves the creation of some children who will never get the chance to live due to risks inherent in their genome. We will never know if their risk of cancer would actually become cancer, or at what stage of life it would occur. These babies are instead thrown out and incinerated in ovens; a tiny holocaust of tiny victims.

Left unsaid is that this process—the selection of some lives that get to be lived and the discarding of others in order to “improve” the human race—is the very definition of eugenics.

Per the National Human Genome Institute Project, eugenics is the “discredited belief that selective breeding for certain inherited human traits can improve the ‘fitness’ of future generations.” It is discredited because for eugenicists, “’fitness’ corresponded to a narrow view of humanity and society that developed directly from the ideologies and practices of scientific racism, colonialism, ableism, and imperialism.”

The enlightened people at Orchid would never think of themselves as backing scientific racism or colonialism—the company is based in San Francisco after all—but there is that little doubt that discarding children who might have lived full lives despite being a type 1 diabetic (as I am) is the definition of ableism.

So where is the public backlash against this kinder, gentler version of mass killing? Because we have forgotten our history, it is virtually non-existent.

Eugenics Past and Future

As we get further removed from World War II, we grow less aware of just how fashionable, and horrible, eugenics was in the decades that preceded it. In my home country, the father of Canada’s much beloved (and highly dysfunctional) public health care system, Tommy Douglas, favored state-sponsored eugenics programs to sterilize “subnormal” families. For Douglas, that meant families with “low mental rating…anywhere from high-grade moron to mentally defective,” along with below normal “moral standards” such as the sexually promiscuous or those involved in prostitution.

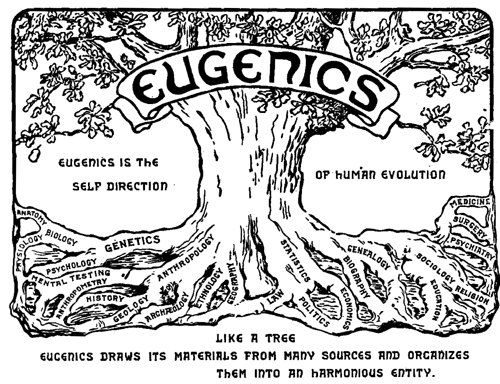

This was a commonplace assumption for many in the West at the time. The U.S. has its own long, egregious, and largely unknown history of eugenics and forced sterilization, which received significant support from early twentieth-century elites and became embedded in state policy. The assumption and hope of eugenics was the “improvement” of the genetic stock of human kind, as shown in this illustration from the Second International Conference of Eugenics in 1921:

Logo of the Second International Congress of Eugenics, 1921 (photo credit: American Museum of Natural History)

While in the 1920s, 1930s, and even into the 1940s the dirty work was largely done under the aegis of the state, Siddiqui wishes to perform eugenics on a purely personal basis. What could be better than parents themselves choosing to remove “undesirable stock” from the tree of human life?

Siddiqui’s evocation of the desire for “superbabies” should, however, give us pause. The twentieth-century eugenics movement only fell out of favor when it was discovered that the Nazis, under their policy of “racial hygiene,” committed unspeakable horrors to secure the dominance of Aryans as the Übermenschen.

The same horrors happen within Siddiqui’s program, including the burning of human flesh, they are just hidden within the cordon sanitaire of medical and scientific labs.

Assumptive Killing

Even if we buy into the “superbabies” concept, it is a shallow idea on which to build a life.

For one, there is no guarantee that genetic predisposition to something will actually result in that thing happening—not everyone with a genetic predisposition for breast cancer gets breast cancer. Separately, if someone gets cancer at age 76, is that a life that should be discarded? On what basis could parents even hope to know such things? They can’t, and neither can any “certified genomic counsellor” offering friendly suggestions. Orchid’s marketing doesn’t mention epigenetics and does not appear to account for the fact that some diseases (say, type 1 diabetes) no longer detract from a full life the way they once did. What is a death sentence at time X might be a minor inconvenience at time Y.

And even absent disease, my guess is that Siddiqui’s superbabies (bless them) will find themselves just as plagued by the travails of life as any other child. They will disappoint their parents, refuse to do their homework, fail French class, or perhaps they’ll acquire some new disease that we haven’t yet discovered.

This hints at the bigger issue with Orchid: It doesn’t account for the deeper things—happiness, virtue, joy—that constitute what it means to be a successful or thriving human being.

What Is Human Life For?

Even if we could raise the “average” according to the mores and assumptions of our age, a new average would take its place. Everything regresses to the mean. Greatness is one of two things: either an eternal, objective standard or, as we see from Tommy Douglas and the Nazis, simply the wishes and preferences of the powerful in a very small slice of human history.

There’s one final issue at play.

“The real objection,” according to C.S. Lewis, is that “if man chooses to treat himself as raw material, raw material he will be.” This insight of Lewis, as further explored by Canadian hip-hop artist Shad K in his concept album Tao (which I highly recommend), leads to dark places. Here’s Lewis again:

We are always conquering nature. “Human nature” will be the last part of nature to surrender to man. The battle will indeed be won but who, precisely, will have won it? For the power of man to make himself what he pleases means, as we have seen, the power of some men to make other men what they please.

Note here that with Orchid, despite the soothing talk about reducing suffering for the child, it is not really the child that is the center of attention; it’s the parents. The child who, despite their disease, could be nurtured and loved and perhaps even live a satisfying life with the support of their parents, is discarded in order to please them; to make their lives easier and less stressful.

Siddiqui’s project is simply a more sophisticated, “scientific” attempt to impose the control of modern helicopter parents who worry about skinned knees and cheat to get their kids into the Ivy League. Again, Lewis provides clarity:

Each generation exercises power over its successors: and each, insofar as it modifies the environment bequeathed to it and rebels against tradition, resists and limits the power of its predecessors.

So what’s the alternative?

Trouble, Joy, Strength

It’s a twofold project. First, we must rediscover what it means to be objectively super human, and through this to discover that super and average can be found within the same person.

What does it mean to be a superbaby? The best way to discover this is to analyze what people value at the end of life.

And those things, those “eulogy virtues” as David Brooks calls them, are far more valuable than the physical traits that Siddiqui promotes. I’m a Christian, so I have particulars on what those virtues are, but at base they are not going to be found through genetic screening but through a lifetime of hardship and discipline aimed at doing the right thing again and again. Understood this way, the challenges faced by children who might possess an “undesirable” genetic trait may lead them to become above-average human beings. And it may do the same for their parents.

That’s not to say it will be easy. A close friend of mine has a daughter with Down syndrome. It’s extremely hard, and yet their lives, our lives, indeed, the world, is better off because she exists. Her existence brings ineffable joy, comfort, and love. The famed French statesman Charles De Gaulle likewise had a daughter with Down syndrome. He put it this way: “Her birth was a trial for my wife and myself. But believe me, Anne is my joy and my strength. She is the grace of God in my life. She has kept me in the security of obedience to the sovereign will of God in my life.”

You do not have to be a Christian, or even be a theist, to appreciate what his daughter’s life brought to De Gaulle. Her existence provided a totally different perspective on life that, at least in part, contributed to his greatness on the world stage against the very people who would have killed and burned her.

If joy and strength is what you measure, you’ll find yourself with a whole new appreciation for the average Joe.

That is exactly what I want my own children to hear. My two genetically identical sons are taking different paths. One is studying construction engineering at his local community college, while the other is pursuing astrophysics. And I love them both, not because of their career choices but because they are good young men.

So, if you’re a parent or thinking of children, I encourage you to leave the Siddiqui superbaby party and embrace the average. Be the type of parent that strives to shape a child that is objectively good and you will find that they, and you, become great.

"My guess is that Siddiqui’s superbabies (bless them) will find themselves just as plagued by the travails of life as any other child." - Correct, which undermines the central argument of the piece.

If all people face challenges, including challenges that strengthen them, and bring opportunities for joy and virtue to their community, then removing one specific challenge (an identifiable disease) will not adversely affect that person's or their community's ability to embody "what it means to be a successful or thriving human being".

The author does not posit, though perhaps he should boldly do so, that people with a genetic predisposition to greater disease and disability are more moral or have more meaningful lives. That would be an interesting position, and would be an effective riposte to Orchid's offering. Indeed, it would then logically follow that we should genetically screen for and actively promote such greater disease propensities. That of course is a position the author would not take.

That leaves us in the unremarkable position of just saying that the current (arbitrary) genetic predisposition to disease is correct and should not be tampered with. That kind of defense of the status quo is fairly uncontroversial, but not without its own problems, as it opens us to questions of what other status quo circumstances we should not tamper with.

Should we not undertake any medicine or technology, or improve our nutrition, or even participate in any activism or philosophical argument, because each of these alter our received status quo and materially change our life outcomes, our struggles, our opportunities for joy though sacrifice? That is also clearly not a position the author would take. Hence, we are left wondering what differentiates Orchid's particular intervention from all the other interventions the author presumably supports.

The cynical answer would be that the author objects to the destruction of embryos through IVF technology, but does not see that as a winning argument, so builds a facade about joy through sacrifice. Less cynically, we could just say that the author needs to re-work this position with more rigor, to better identify what makes this practice meaningfully different from all of the other life-saving and life-easing interventions we have embraced over the last 500 years. Focusing on the despicable history of eugenics and the hubris of man is certainly a good start, but it's not a complete argument.

As an aside, the charge of ableism is accurate. But this is also not as powerful as the author might hope. Is it ableist to set a bone correctly in order to prevent future disability? Yes. Is it ableist to reduce an infant's fever to prevent deafness? Yes. Is it ableist to properly care for a serious burn to preserve function in the limb? Yes, all ableist, and all welcome and uncontroversial practices.

""[...] the challenges faced by children who might possess an “undesirable” genetic trait may lead them to become above-average human beings.""

I wish things worked that way. I don't object to the general message of the article per se, but I'm not averse to parents wanting their children (boys especially) to have the most potential for success (social or otherwise) and for preferential treatment. The stakes are not nearly as high for girls, regardless what women want to think. I think most men recognize as eugenics the sexual selection behavior that deems them inferior and excludes them (to the extent that selection is based on what the choosers consider to be superior, or what is socially determined to be superior).