Trump’s Shipbuilding Imperative

A libertarian radical sank America’s maritime industry. It needs to be restored.

By Michael Lind, a Tablet columnist, a fellow at New America, and author of Hell to Pay: How the Suppression of Wages Is Destroying America.

“To boost our defense industrial base, we are also going to resurrect the American shipbuilding industry, including commercial shipbuilding and military shipbuilding,” President Trump announced on March 4th during his joint address to Congress. “And for that purpose, I am announcing tonight that we will create a new office of shipbuilding in the White House and offer special tax incentives to bring this industry home to America, where it belongs.”

According to reports, an executive order that is being drafted would mandate the imposition of fees on vessels built or flagged in China that enter American seaports. In February, the United States Trade Administration (USTR) proposed a $1.5 million fee for any Chinese-made ship that docks at a U.S. port.

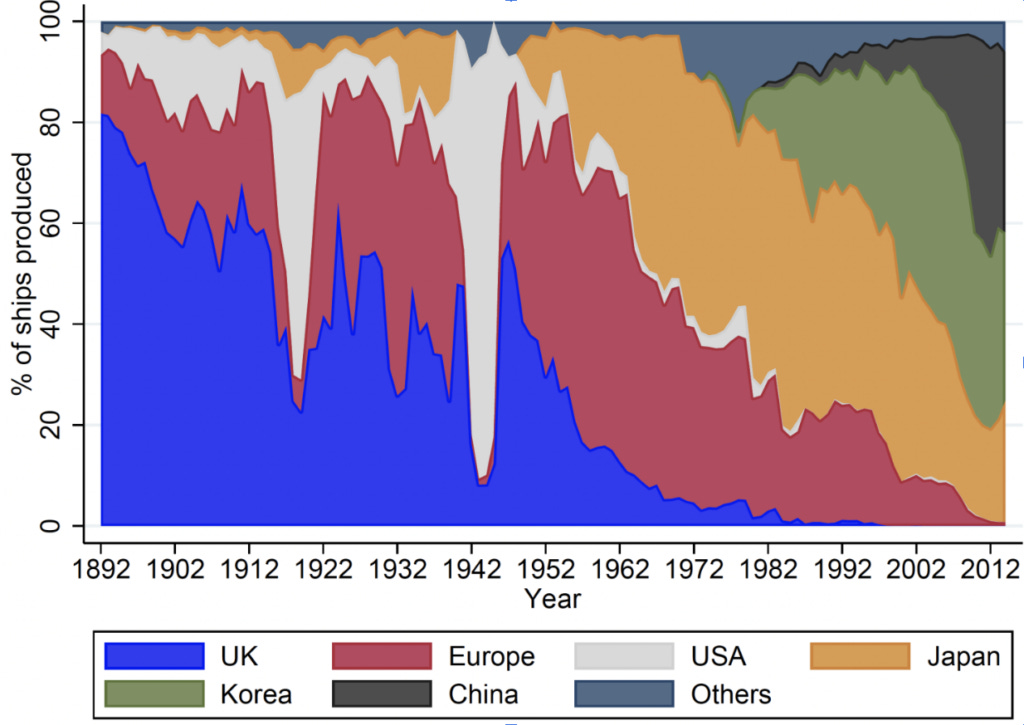

In addition, a new Maritime Security Trust Fund would be used to provide grants, loans, and tax credits for domestic shipbuilding. America’s loss of shipbuilding capacity to China during the era of ill-conceived free-market globalism from Reagan to Obama has been even more catastrophic than the loss of American manufacturing to Chinese competitors. Most of the goods shipped across the oceans to and from the U.S. are in ships built in China (51%), South Korea (28%), or Japan (15%). China today is the world’s largest commercial shipbuilder, responsible for more than half of all shipbuilding. America’s share of the global commercial shipbuilding market is a mere 0.10%.

Source: CEPR, Industrial policy: Lessons from shipbuilding

The prospect of Chinese maritime hegemony is driving these efforts. In January of this year, the Department of Defense blacklisted Chinese container shipping company COSCO, the China State Shipbuilding Company (CSSC), and the China National Offshore Oil Corporation (CNOOC), defining them as “Chinese military companies” prohibited from shipping U.S. military cargo.

In December 2023, Biden’s Navy Secretary Carlos Del Toro told Congress that America must once again become a “global leader in shipbuilding” if it wants to remain a naval power. A two-year investigation by the Biden administration concluded that China’s domination of global commercial shipping is the result of unfair practices.

To reduce dependence on Chinese shipyards, the Biden administration sought to encourage Japanese and South Korean shipbuilding companies to invest in American shipyards.

The market fundamentalist mentality that produced this disaster is illustrated by a statement to CNBC by Ben Nolan, a financial analyst for Stifel Financial: “The fact is China can build ships a lot cheaper than we can, just like we have seen over the last three decades companies turning to Bangladesh, China, and other Asian countries to manufacture tennis shoes and clothing. They are the economically viable choice.”

This claim ignores the fact that, throughout history, naval powers have gone to great lengths to supplement the fighting ships of their navies with a flourishing “merchant marine,” consisting of civilian ships built in national shipyards with national owners and national crews that can be conscripted to reinforce the nation’s navy during times of war and international tension.

***

In The Wealth of Nations (1776), Adam Smith made an exception from his general support for free trade to endorse protection of Britain’s civilian shipping industry. The British Navigation Acts, first enacted in 1651 by Oliver Cromwell’s Puritan regime, and subsequently renewed and expanded until their repeal in 1849, sought to encourage a large British merchant marine by requiring the transportation of goods to and from Britain and its colonies on British-built ships with largely British crews. In this way, the island nation maintained a large civilian fleet which could be drafted to support the British navy during wars. Recognizing the strategic importance of this maritime protectionism, Smith wrote:

National animosity at that particular time [the 1650s] aimed at the very same object which the most deliberate wisdom would have recommended, the diminution of the naval power of Holland, the only naval power which could endanger the security of England…The act of navigation is not favorable to foreign commerce, or to the growth of the opulence that can arise from it… As defence, however, is of much more importance than opulence, the act of navigation is, perhaps, the wisest of all commercial regulations of England. (emphasis added).

For most of the 19th and 20th centuries, Britain led the world in shipbuilding, along with Germany and the Scandinavian countries. Having industrialized behind a wall of protective tariffs, the U.S. surpassed Britain as the largest manufacturing economy by World War I but lagged behind in shipbuilding. After the US entered the war in 1917, the U.S. Shipping Board (USSB) created the Emergency Fleet Corporation (EFC), which by 1922 had made the U.S. merchant marine the largest and most modern in the world, with 2,312 ships.

In the spirit of Adam Smith, Congress passed the Merchant Marine Act of 1920, commonly known as the “Jones Act,” reserving shipping on America’s rivers and intracoastal waterways for U.S.-flagged vessels in order to preserve American shipbuilding capacity during the collapse in demand for ships after World War I. The Merchant of Marine Act of 1928 further sought to foster a healthy American merchant marine by offering subsidies in the form of mail transportation contracts for American companies that built ocean-going ships (the federal government similarly used mail contracts as an excuse to subsidize America’s infant aerospace industry around the same time).

The “Magna Charta of American Shipping,” the Merchant Marine Act of 1936, sought to strengthen the merchant marine in the interest of national defense by providing two subsidies to American shipbuilders—the construction differential subsidy, which paid up to 50% of the difference between U.S. shipping costs and the lower costs of subsidized foreign competition, and the operating differential subsidy, a direct payment to U.S.-flag operators to overcome unfair competition by foreign-flag ships.

Enacted with an eye to national security, the 1936 Act created a federal training program for merchant seamen and established the Maritime Commission to oversee a multi-year program to build civilian ships that could be used by the Navy in wartime. Before the U.S. entered World War II following Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor and Hitler’s subsequent declaration of war on America, the U.S. Merchant Marine played a key role in the Lend-Lease program, whose convoys supplied Britain and the other nations battling the Nazis. Once the U.S. entered the war, the Merchant Marine—soon the largest civilian navy in the world and in all of history—was essential for military logistics in the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. More than 9,000 of the 243,000 mariners in the Merchant Marine were killed during the war, a higher proportion than in any branch of the regular military.

On D-Day, June 6, 1944, 200 of the 7,000 ships that ferried the Allied invasion force to the beaches of Normandy were U.S. merchant ships.

In the Cold War that followed, more than 250 merchant marine ships were used during the Korean War from 1950-54, while 175 fleet transports crewed by merchant marines, along with U.S.-flagged merchant ships, supplied the American military during the Vietnam War.

Ironically, it was the administration of President Ronald Reagan, an ardent Cold Warrior, that crippled American shipbuilding and America’s merchant marine. The individual most responsible for the destruction of America’s commercial ship construction industry was Martin Anderson, who served in the Reagan White House as assistant to the president for policy development, in charge of economic and domestic policy.

Martin Anderson was an anti-statist radical, who, with his wife Annelise Graebner Anderson, belonged to the cult-like Objectivist circle led by the Russian-American libertarian guru Ayn Rand in the 1960s. The Andersons took courses in Objectivist ideology at the Nathaniel Branden Institute, named for one of Rand’s disciples and lovers. Through Ayn Rand, this fringe-libertarian power couple met another one of her disciples, the future Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan, who helped Anderson pursue a career in government as an adviser to Richard Nixon and later as the only full-time economic advisor on Reagan’s presidential campaigns in 1976 and 1980.

In a eulogy in 2015, the Atlas Society, named after Ayn Rand’s libertarian novel “Atlas Shrugged,” boasted that Martin Anderson, true to libertarian ideology, had successfully thwarted federal efforts to identify and deport illegal immigrants:

For example, at a cabinet meeting early in Reagan’s first term, Attorney General William French Smith presented a plan to require a national ID card for anyone working in the United States, in part to deal with illegal immigrants. Anderson, who normally didn’t speak at those meetings, raised his hand and, when called on by Reagan, explained that such a card could easily be faked or lost. So why not tattoo a number on everyone’s wrist? Reagan immediately understood the illusion to Nazi practices and the threat such a “Papers please” dictate would pose to liberty. The proposal died there and then.

Martin Anderson was as indifferent to maritime security as he was to border security. Acting on the advice of Anderson, who dogmatically opposed government subsidies, President Reagan in 1981 ended the existing subsides for U.S. ship construction through the Merchant Marine Act of 1970, signed into law by President Nixon: Title V (subsidies for the construction of foreign-trade ships), Title VI (subsidies for operation of foreign-trade ships), and Title XI (loan guarantees for U.S.-flag ships built in U.S. shipyards).

Annelise Graebner Anderson, Anderson’s wife and fellow Randite libertarian, who had been appointed to head Reagan’s Office of Management and Budget, eliminated the subsidies for U.S. shipbuilding from the administration’s first budget request.

The results were devastating to the United States as a maritime power. As one history notes, “when the Reagan Administration decided to stop subsidizing US merchant shipbuilders, they did so without any similar actions taken by other shipbuilding countries. This means that while the American shipbuilders had to walk on their own two feet, foreign shipyards were being heavily subsidized by their country.”

In 1975, the U.S. had 77 commercial ships on order. As a result of the Reagan administration’s abolition of construction differential subsidies, the U.S. sold only eight commercial ships over 1,000 gross tons between 1987 and 1992.

By 2023, American shipyards had only five sea-going commercial ships under construction, while China had 1,749.

The abandonment of the maritime industry caused a massive loss of jobs and technological skills.

Source: ENO Center for Transportation, Decline in U.S. Shipbuilding Industry: A Cautionary Tale of Foreign Subsidies Destroying U.S. Jobs

Today, global shipbuilding is nearly monopolized by China, Japan, and South Korea. New commercial ship builds (bulk carriers, dry cargo ships, passenger ships and tankers) are dominated by China (1,287), with Japan (387), and South Korea (316) bringing up the rear. The U.S. in 2024 had only 107, fewer than Indonesia, the Netherlands, Turkey, Russia, Italy, and India.All three East Asian countries successfully have used subsidies and other mercantilist methods to drive other countries, including the U.S., out of the shipbuilding industry.

Before World War II, Japan had been the third largest shipbuilding country, following Britain and the U.S., and its shipyards were mostly spared from wartime destruction. Japan’s modern shipbuilding industry was built with the help of American knowhow and capital. A study in 1966 noted that “there seems to be one particular factor favoring Japanese shipbuilding: Capital is supplied on an increasing scale from the United States. In this way, United States technical know-how and skill is combined wit39.8% of the global commercial shipbuilding market—more than the share of the next five shipbuilding nations combined.

From the 1960s to the 1980s, Japan produced half of the world’s shipbuilding tonnage, before losing market share to South Korea and China, with their own subsidies and even cheaper labor.

According to the data firm Dunn and Bradstreet:

Japanese and South Korean shipbuilding industries received substantial government support during the 1970s and 80s, which helped them to emerge as top players in the world. While Korean government provided a major thrust to the industry under the HCI policy [Heavy-Chemical Industry Drive] that included capital incentives, trade incentives and tax holidays, the Japanese government provided huge subsidies in the form of easy finance and loan deferments…

In 2006, the Chinese communist regime identified shipbuilding as a “strategic industry” and funded it accordingly. China quickly surpassed South Korea and Japan to dominate global shipbuilding with the help of three kinds of subsidies: “entry subsidies” that encouraged new shipyards, including simplified licensing and below-market land prices; “investment subsidies” including preferential tax policies and low-interest financing with the help of dedicated banks; and “production subsidies” in the form of subsidized inputs, including cheap stee, export credits, and buyer financing to encourage foreign purchases of Chinese-made ships.

Chinese shipbuilding provides a classic case of a nation “dumping” subsidized products at a net loss on markets in order to wipe out the industries of rival countries. A study in 2024 found that “70% of China’s output expansion occurred via stealing business from rival countries. There is evidence (backed by our cost estimates) that Chinese shipyards are less efficient than their Japanese and South Korean counterparts; thus, the transfer of shipbuilding to China constitutes a misallocation of global resources. Second, China’s industrial policy for shipbuilding led to considerable declines in ship prices…. In other words, the net return when incorporating the cost to the government was a negative 82%, with entry subsidies explaining a lion’s share of the negative return.”

A 2014 study for the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) found that Chinese subsidies between 2006 and 2012 “led to substantial reallocation of ship production across the world, with Japan, in particular, losing significant market share. They also misaligned costs and production, while leading to minor surplus gains for shippers.” A counterfactual analysis showed that “in the absence of Chinas government plan, Chinese market share is cut to less than half, while Japan’s share increases by 70%.”

Thanks to subsidies and other forms of government support and cheap and unfree labor, China makes more ships than the rest of the world combined and now has 200 times the shipbuilding capacity of the U.S.

In 1999, China’s share of shipbuilding by tonnage was only 5%; in 2023 it surpassed 50%.

In 2024, the market share of China in container ships was 81%; in bulk carriers, 75%; and in liquefied petroleum gas carriers, 48%.

The majority of China-built ships are purchased by foreign companies, permitting China to enjoy economies of scale in the industry and dominate global markets.

Unlike the U.S., which has maintained specialized naval shipyards while allowing commercial shipbuilding to collapse, China has followed a strategy of “military-civil fusion,” supporting its naval buildup with its commercial shipbuilding capabilities.

Military-civil fusion also informs other Chinese efforts to achieve global maritime hegemony. Chinese companies now control or partly own more than a hundred ports in Asia, Africa, the Middle East, Europe, and the Americas, including investments in the Port of Los Angeles pier and Seattle container terminals.

China reinforces its ability to surveil and weaponize global shipping by embedding its LOGINK, a ship-tracking software, into ports and terminals around the world.

***

By manufacturing most of the world’s commercial ships, operating ports in every region through state-influenced companies, and using state-controlled software to track shipping around the world, in addition to creating the world’s largest navy, China’s authoritarian regime has come in striking distance of global maritime supremacy, while America slept.

Even Colin Grabow of the Cato Institute, while taking the ritual libertarian potshot at the Jones Act, concedes that subsidies may be necessary to revitalize American shipbuilding in the face of foreign mercantilism:

As I’ve written before, however, this doesn’t necessarily mean that the notion of shipbuilding subsidies (or more accurately, additional subsidies) should be dismissed. If the construction of large merchant ships in sizable numbers is indeed critical to U.S. national security—a not entirely obvious proposition given the limited overlap between commercial and military shipbuilding—then the industry should be supported in the most efficient and transparent manner possible (which is to say not via the Jones Act, whose U.S.-built requirement should be repealed as part of any deal for new subsidies).

In 1944, General Dwight Eisenhower observed that “when final victory is ours there is no organization that will share its credit more deservedly than the Merchant Marine.”

In the 20th century, America’s civilian shipbuilders and merchant mariners were indispensable to the defeat of Imperial Germany, the Axis Powers, and the communist bloc far from America’s shores—only to be betrayed and abandoned by misguided market fundamentalist policymakers in Washington in the 1980s. After half a century of neglect, American leaders of both parties have belatedly realized that the United States cannot be a great naval military power without also being a great civilian shipbuilding power with a world-class merchant marine.

Rebuilding the American civilian shipbuilding industry will be costly and difficult. But the alternative is global maritime domination by the dictatorship in Beijing.