You Can’t Spell 'Defense Industrial Base' Without 'Industrial Base'

And more from this week…

It’s been an amazing year here at Commonplace and for the Understanding America newsletter. Our audience has grown by an order of magnitude over the course of the year, and we are so grateful to all of you for reading, sharing, and commenting. What better way to celebrate the year’s end than telling your friends and family to subscribe? You can even print this out and stuff it in a stocking!

We start this week with news from the White House on defense contractors. Daniel writes:

Reporting this week indicates that President Trump might soon sign an executive order to limit share buybacks, dividends, and executive pay for defense contractors whose projects are over budget and behind schedule, part of an effort to bring more discipline to what the administration has described as an “expensive, slow-moving and entrenched” defense industry. The action would complement the Pentagon’s recent procurement process overhaul, intended to reduce bureaucracy, boost capacity, improve capabilities, and address “unacceptably slow” acquisition systems stemming from fragmented accountability and misaligned incentives. The basic idea of these efforts is simple: If Washington’s current contracting structure cannot reliably deliver on time and on budget, then the government should stop acting like an annoyed customer and start behaving like the actual underwriter it is, using its leverage to reshape incentives accordingly.

Details of the rumored executive order are scarce, and it’s unclear what final form it might take. But the administration has rightly focused its ire on how financial engineering in the defense sector has created perverse incentives that are incongruent with a robust and innovative defense industrial base capable of securing the national interest.

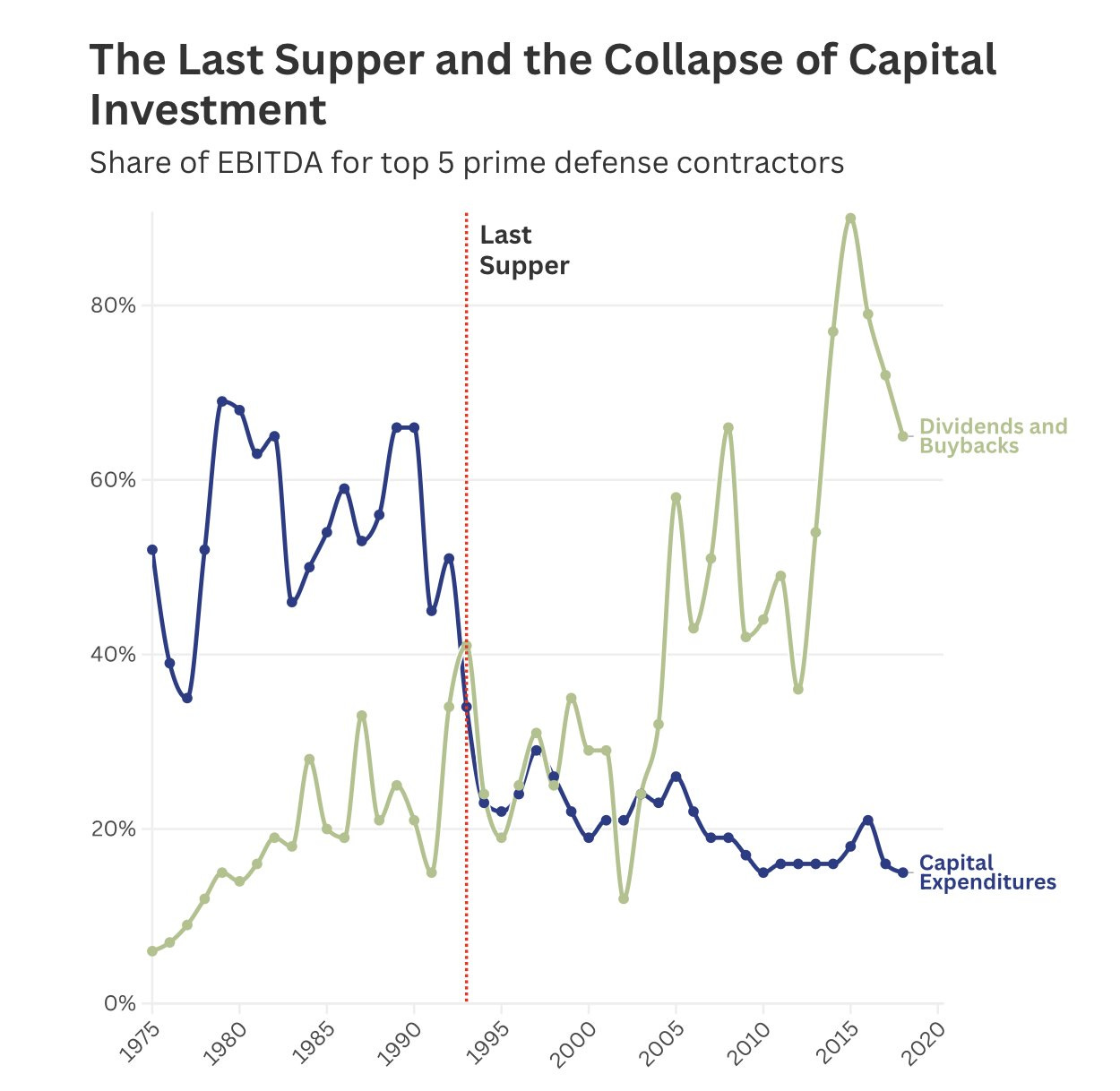

After the 1993 “Last Supper” pushed the Pentagon’s supplier base into a small set of giant primes, the industry’s financial posture shifted. In “Big Stick Economics,” one of my favorite essays published in Commonplace this year, Oren and American Compass policy advisor, Mark DiPlacido, detail how the major defense contractors drifted from productive investment to financial extraction as sectoral consolidation narrowed the field of competition. They apply the straightforward taxonomy developed in American Compass’s “The Corporate Erosion of Capitalism”: firms can be Growers, which tap financial markets for needed capital; Sustainers, which use profits to maintain or grow their capital base while returning some capital to shareholders and creditors; or Eroders, which disgorge profits so rapidly, instead of investment, that they consume fixed capital faster than they make new capital expenditures. They write:

For the 20 years from 1974 to 1993, the primes collectively operated as a Sustainer in every single year. The individual firms were Sustainers in 69% of years and Eroders in 18%. After 1993’s “Last Supper,” that behavior flipped on its head. In both 1994 and 1995, all five primes were Eroders. For the next decade, the primes collectively operated as an Eroder every year. Over the 25 years from 1994 to 2018, the individual firms were Sustainers 33% of the time and Eroders 67% of the time. They returned $240 billion to shareholders through buybacks and dividends while making less than $90 billion in capital expenditures.

That contrast—$240 billion out the door to shareholders, less than $90 billion in productive capital investments—perfectly illustrates the pathology of “shareholder capitalism” that we’ve long criticized at American Compass. Share buybacks, the purest form of financial engineering, raise earnings per share by shrinking the denominator, boost short-term stock prices, and inflate executive compensation. The result is a corporate environment in which executives can be paid handsomely for making the stock perform well, even if the firm’s long-run capacity degrades.

The typical defense of this behavior is that capital returned to shareholders will be “reallocated” toward better uses elsewhere. But in an economy where firms are buying back their shares at a record pace, it’s reasonable to ask: reallocated to what, exactly? If corporations consistently return cash rather than deploy it, then the story we’re watching is not one of efficient capital markets matching savings to productive opportunity. It’s a story of incentives steering managers toward extraction because extraction is what financial markets—and boards, and compensation committees—reward.

This is why the Trump administration’s instinct—imposing limitations on payouts and compensation pegged to performance—is directionally correct, especially in the defense sector. The government, after all, is not merely a customer in this market. It designs the procurement rules and funds the production lines. If a program is failing, the government is within its rights to demand that cash stay inside the firm until the problem is fixed.

But the same problem extends far beyond the defense sector. In all the places where the United States needs more capital investment—energy infrastructure, shipbuilding, advanced manufacturing, critical minerals, residential housing—financial engineering can pull in the opposite direction. If Washington is willing to say that buybacks and dividends in the defense sector are inconsistent with the national interest, it should apply the same analysis to other industries that require greater capital investment. No principle of economics would limit the disconnect between shareholder return, industrial capacity, and economic progress to tanks and missiles. — Daniel

SPEAKING OF FINANCIALIZATION…

Flashing Out: The Wall Street Journal reports on “High-Speed Traders Feuding Over a Way to Save 3.2 Billionths of a Second.” High-frequency traders are no longer satisfied trying to beat competitors by milliseconds with faster broadband connections to trading floors. They’re now fighting with each other over algorithms that manipulate their connections to the floors in pursuit of nanosecond advantages worth hundreds of millions of dollars. Seems super productive.

Up In Flames: The New York Times, meanwhile, has “Private Equity’s New Source of Profit: Volunteer Fire Departments.” This is a good example of what Oren has called “moral arbitrage,” in which private equity tracks down niches not run ruthlessly to extract maximum cash flow from consumers, buys up firms less profitable than they otherwise might be, and then turns the screws. Seems super productive.

But better investment news also continues rolling in too. In an early example of JPMorgan’s newfound commitment to investment in the real economy, it is helping to finance a $7.4 billion critical minerals project led by a Korean firm with U.S. government support as well (Wall Street Journal).

That’s good industrial policy, and contrasts with news out of Detroit… where “Ford Takes $19.5 Billion Hit in Detroit’s Biggest EV Bust” (Wall Street Journal). One can imagine a world in which the Biden administration had focused the bulk of its own industrial policy efforts and dollars on critical minerals and reindustrialization instead of green boondoggles. Sadly, that is not the world we live in. That reality sometimes gets raised as a critique of industrial policy writ large—see, once you embrace industrial policy, you’re stuck with progressives using it foolishly. But of course, that’s what politics is for. Progressives can use any policy mechanism foolishly, and they can and will pay a political price when they do.

As Vice President JD Vance observed at an American Compass event back in 2023:

Joe Biden’s doing a lot of crazy crap with the Defense Department that I don’t think that he should do. Does that mean we shouldn’t have a U.S. military? No. It means we should advance a political program that’s popular, and that can win, so that when we win, we can get to do with the military what we want to do. And in fact, the real solution here, is to win a durable enough governing majority, not that we’re going to win every election, but that the craziest stuff that the left tries to do, it stops trying to do, because it realizes there are political downsides to doing it.

SOME GOOD WEEKEND READS

If you’re Very Online, or heck, even A Little Online™, you’ve already read Jacob Savage’s “The Lost Generation” at Compact. But if you’re not, well, you should read it:

But for younger white men, any professional success was fundamentally a problem for institutions to solve. And solve it they did. Over the course of the 2010s, nearly every mechanism liberal America used to confer prestige was reweighted along identitarian lines.

Then read Ross Douthat on the topic too:

Even if you set aside the moral problem of collective punishment — is a young white man who wants an academic job in 2020 responsible for how white men behaved in 1960? — and the legal issue of discriminating on the basis of race and sex (quite a lot to set aside!), you are still left with the political problem: This particular attempt at revolution has created a cadre of potential counterrevolutionaries with a clear material grievance against the entire system, especially against its claims to moral superiority on issues related to race.

At The Dispatch, Megan McArdle wrote about “The Brother I Lost. What a deathbed confession and a long-disappeared sibling taught me about a woman’s right to choose.”

And in the Wall Street Journal, “The Chinese Billionaires Having Dozens of U.S.-Born Babies Via Surrogate” is self-recommending (the article, not the conduct of the Chinese billionaires). While obscene abuses of our open society and our market economy are on your mind, head over to the New York Times as well for “Hospitals Cater to ‘Transplant Tourists’ as U.S. Patients Wait for Organs.” Even by the gross standards of profit maximization in the U.S. health care system, it’s fairly shocking to learn that hospitals

have advertised abroad, promoting short wait times and concierge services, particularly to patients in the Middle East, where about two-thirds of overseas transplant recipients are from. … A handful of hospitals are increasingly catering to overseas patients, who make up an ever-larger share of their organ recipients: 11 percent for hearts and lungs at the University of Chicago; 20 percent for lungs at Montefiore Medical Center in the Bronx; 16 percent for lungs at UC San Diego Health; 10 percent for intestines at MedStar Georgetown University Hospital in Washington; and 8 percent for livers at Memorial Hermann-Texas Medical Center in Houston. In many countries, this would be illegal.

Ya think? How is it not illegal here? We need the brief from the Mercatus Center on the laudable efficiency of the practice and perhaps how we’re really all better off for it because surely the additional revenue is being invested in research into other life-saving cures…

WHEN IS A MARKET NOT A MARKET? WHEN IT’S A HEALTH CARE MARKET

Or maybe, the unique challenges and dilemmas of health care make it uniquely ill-suited in many situations to benefit from the wonders of market forces. American Compass is beginning to dive into the issue, and Commonplace had two excellent essays on it this week (if we do say so ourselves).

How Health Care Became a Financialized Hellhole, by Oren Cass. “ACA subsidies are a bailout for a financial product groaning under the weight of its own poor design. It has reached a price where politicians feel they must help even households with incomes more than four times the poverty line in order to deliver the holy grail of universal coverage. Meantime, access to actual health care is generally in decline and Americans are generally in lousy health. There is a hole in the bucket.”

The Drug Price Delusion, by Michael Lind. “The challenge, in our time as in Jefferson’s, is in balancing the need to incentivize innovation with the need to prevent drug companies from abusing their government-created monopoly power by extracting rent or excess profits at the expense of patients and taxpayers. … As in many other American industries, pharmaceutical firms have shifted their emphasis from production to financialization, using market power to extract rent from patients, insurance companies, businesses, and the government.”

If you’re still feeling good about the U.S. health care system after all that, head over to Bloomberg’s “Cancer Capitalism” series. “One Generic Cancer Drug Costs $35. Or $134. Or $13,000.”

CHECKING IN ON THE CHINA CHALLENGE

The Washington Post editorial page, whose writing Jeff Bezos seems to be sourcing from Temu these days, deserves an award for producing the worst column written about the U.S.-China relationship in a long while. Are U.S. Tariffs on China Working? No, says the Post:

The latest evidence suggests they haven’t achieved their stated goals. China’s trade surplus, the evidence of its industrial overcapacity, cleared $1 trillion for the first time this year. China has more than compensated for its trade war with the U.S. by expanding exports to other countries.

Of course, contained right there in the paragraph (more than compensated for its trade war with the U.S.) is an acknowledgment that the U.S. tariffs have achieved their goals, which concern trade with the United States. And as we discuss frequently here at Understanding America (and again below), the “expanding exports to other countries” is itself unsustainable and triggering further consequences that strengthen America’s hand.

Perhaps recognizing this, the Post tries to make the opposite point a few paragraphs later, claiming, “Elevated U.S. levies on Chinese goods have not significantly altered the amount of trade or the trade balance on a bilateral basis, with levels approximately the same in 2024—the last full year for which data are available—as they were in the early 2010s.” But even just glancing at the chart they provide shows this is untrue.

Looking at the data shows the claim to be, well, kind of a lie. The Census data cited is in nominal terms, so comparing a $295 billion trade deficit in 2024 to a $295 billion trade deficit in 2011 actually indicates a decline of more than 25%. But more importantly, China tariffs began in 2018, when the trade deficit was $418 billion. Again, adjusting for inflation, the decline is more than 40%.

And how convenient of the Post to use 2024, “the last full year for which data are available,” when the aggressive tariffs about which they are editorializing came into effect in 2025. If only more recent data were available, which it is, by month, at the page to which they link. Comparing the first 9 months of 2025 to the first 9 months of 2018, adjusting for inflation, the trade deficit with China is down almost 60%.

The Post concludes, “Tariffs aren’t working to correct China’s economic misbehavior or reduce its industrial overcapacity. American policymakers have only fooled themselves into believing they can micromanage the Chinese economy by micromanaging the American economy through trade restrictions.” Of course, the fact that China will not correct its economic misbehavior or reduce its industrial overcapacity is precisely why the tariffs are necessary, and their effects are already so encouraging.

In other China news, on AI chips, House Republicans are pushing back aggressively against White House enthusiasm for selling off American leadership. Legislation filed today, the AI OVERWATCH Act, would build on the export controls proposed in the GAIN AI Act (that got booted from this year’s National Defense Authorization Act) and, importantly, would force the Commerce Department to explain what on Earth it is thinking. The chairmen of the House Foreign Affairs, China, and Intelligence committees are all consponsors.

Relatedly, the Council on Foreign Relations has an excellent report on “China’s AI Chip Deficit: Why Huawei Can’t Catch Nvidia and U.S. Export Controls Should Remain.” Nvidia and its collaborators in the administration have been shopping the claim that China has basically caught up with the United States anyway, so we may as well sell what we can. That’s not true. But the CCP sure is trying, Reuters explains in “How China built its ‘Manhattan Project’ to rival the West in AI chips:

The team includes recently retired, Chinese-born former ASML engineers and scientists—prime recruitment targets because they possess sensitive technical knowledge but face fewer professional constraints after leaving the company, the people said. Two current ASML employees of Chinese nationality in the Netherlands told Reuters they have been approached by recruiters from Huawei since at least 2020.

We’ll say it: Allowing Chinese nationals to work on sensitive technology, whose export to the People’s Republic is banned, may not be a good idea. If that earns us even shinier China Hawk Badges of Shame, we’ll wear them.

Also a bad idea: “This One Gadget Could Give China a Back Door Into the U.S. Power Grid” (Washington Post). “As the United States leans on solar power to meet soaring energy needs, its reliance on a Chinese-made component has created a mounting security threat, according to energy industry executives and congressional investigators who warn it can be weaponized to trigger blackouts.”

WHICH WAY EUROPEAN MAN?

Meanwhile, the award for worst continental punditry goes to Martin Wolf for this effort at the Financial Times, which works from the premise that real democracy requires denying your opponents “the right to seek power democratically,” because Hitler. Europeans are “scarred by the memories of the two world wars” (which ended more than 80 years ago) and suffering from “learned helplessness,” so now they must “rouse themselves” by… supporting Ukraine. That’s it, that’s the plan. Or, that and writing resentful columns that the United States isn’t doing it for them. Learned helplessness, indeed.

Of course, this strategy, not anything emanating from the United States, is the one that will “help put rightwing ‘patriots’ into power across the continent,” through undemocratic means if democratic ones are foreclosed. At least we know the columnists will be ready with their broadsides blaming someone, anyone else.

A close second in the worst-column sweepstakes surely goes to this Oxford lecturer, writing from Brussels, in the New York Times, “Europe Is in Decline. Good.” Anton Jäger suggests “critical integration with China,” especially because “such engagement is vitally necessary for the fight against climate change, an effort now mostly led by China.” (Interestingly, Wolf likewise worried that inadequate leadership on climate is “a way to hand the future to China.”) Of course, the only effort that China is leading in this respect is the one to pump carbon dioxide into the atmosphere.

Best writing in a comedy, meanwhile, goes to French President Emmanuel Macron, for a Financial Times column on the totally unsustainable nature of the EU-China economic relationship in which he declares himself “convinced that by genuinely taking into account each other’s needs and interests, we can establish an international macroeconomic agenda that will benefit us all.” Mmhmm. Adorably, he laments that “placing tariffs and quotas on Chinese imports would be an uncooperative answer” before suggesting, more seriously, “We should not be ashamed of a ‘European preference’ as long as it means supporting strategic production — in automotive, energy, healthcare and tech — within our own borders. Protection against unfair competition is the foundation of resilience.”

In other words, as Michael Pettis writes in the Financial Times column you should read, “Europe Has No Choice But to Intervene on Trade.”

Likewise, Sander Tordoir, chief economist at the Centre for European Reform, chastises The Economist, which “lays out the profound pressure China is putting on EU manufacturing, but then recommends that Europe give up and switch to services.” That, he suggests with admirable restraint, “feels thin.”

The Headlines Behind the Columns…

Wall Street Journal: Why Germany Wants a Divorce With China. Some German manufacturers think once-symbiotic partnership has turned into an abusive relationship and they want out.

Wall Street Journal: All That Cheap Chinese Stuff Is Now Europe’s Problem. Trump’s tariffs have redirected the flow of low-valued packages away from the U.S. into backyard warehouses on the Continent; the ‘new Silk Road.’

Financial Times: VW Gears Up for First Production Closure in Germany in Its 88-year History. Ending manufacturing at Dresden site comes as Europe’s largest auto producer battles weak demand in its key markets.

AND FINALLY, SOME POLL DANCING TO BRIGHTEN THE SEASON

These all caught our eye:

Most CEOs say AI has increased their hiring across levels; most investors say it should.

Most Americans agree, “When it comes to politics and society, nothing really matters because powerful people will always do whatever they want.”

52% of Americans say the economy is currently in recession… and that’s the lowest figure in the past 15 years!

With that, we are signing off for a little break. Will Vivek Ramaswamy find another way to destroy his credibility and political prospects this Christmas? If he does, we’ll be sure to cover it when we return with a double-wide edition on January 2.

Enjoy the holidays!

Although I have worked in manufacturing (Chemical engineering) for 45 years, it was because I liked the work. Most of my engineering classmates ended up richer and traveling to better places working in finanical type fields after 10-15 years. Look at the issues with getting workers to build transfomers. It takes more than a year to train a person to wire up the large units yet the salary is that of a MacDonalds manager in an average city. See https://www.wsj.com/business/the-factory-workers-who-build-the-power-grid-by-hand-4a846658?st=vct3qp&reflink=desktopwebshare_permalink and https://x.com/shanumathew93/status/2001328531792416922?s=66. Add on the terrible situation with housing costs for young people which makes it risky to move to where a factory is and then the factory is closed or "leaned" when bought by private equity. PS It does not help that the current administration is investing their own money in crypto.

Excellent. We owe a public apology to the thousands of serious, competent defense, government, and industrial technology workers—and the business owners who backed them—who warned us for decades while we ignored, mocked, and socially sidelined them. They were treated as backwards while the rest of us chased fast money in information technology and congratulated ourselves for it. A small cohort of patriots and realists stayed in the fight anyway, preserving hard-won materials, manufacturing, and hardware know-how—and without them, we would already be completely irrelevant in the physical world.