Stop Arming Our Adversary

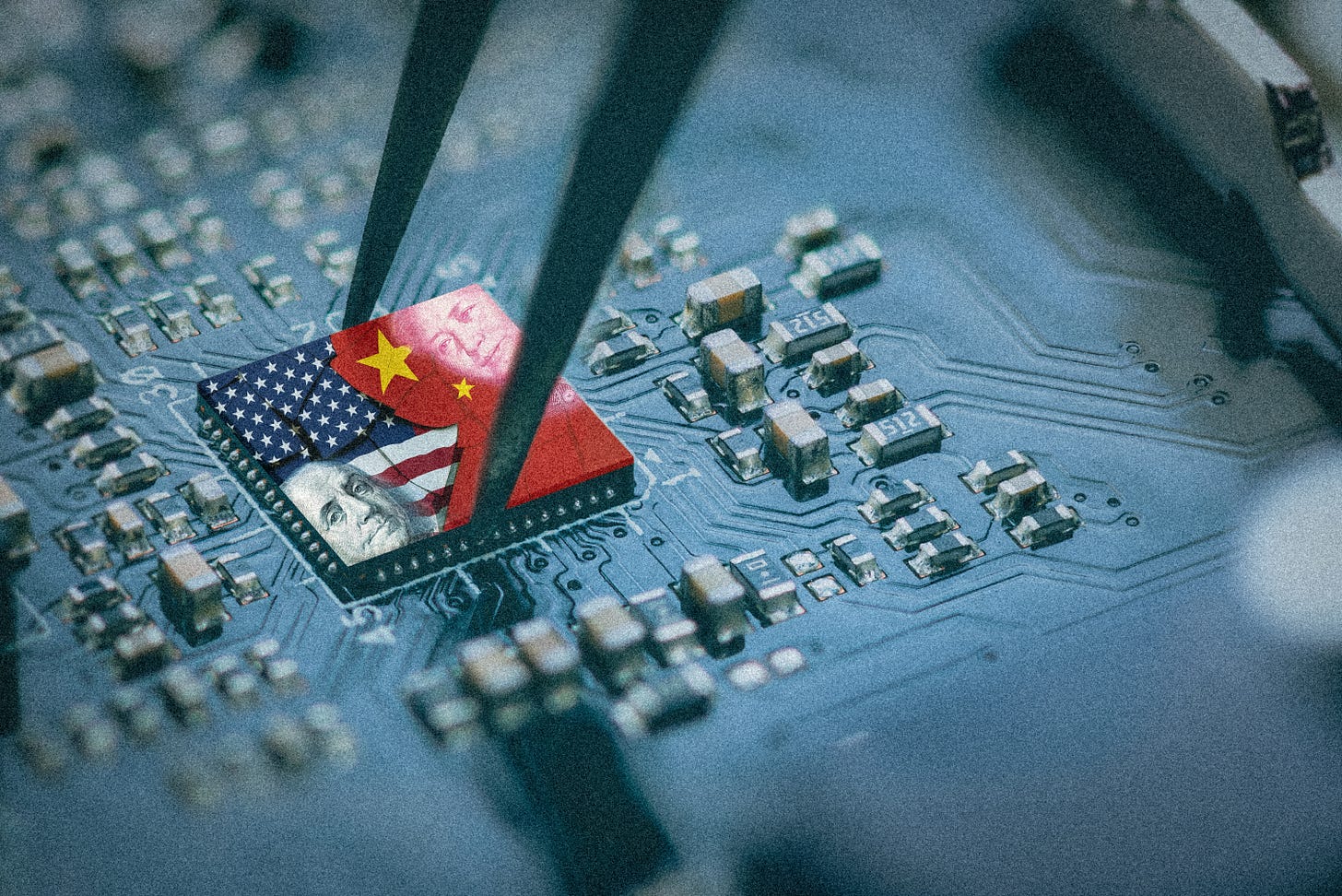

The U.S.-China chips ceasefire won’t last. America needs a plan.

It is a wonderful thing when both the prognosticators of disaster and those actively promoting that disaster are proven wrong. When President Trump met Xi Jinping in South Korea last week, that is exactly what happened with respect to exporting advanced semiconductors to China.

The stakes were high. American chip designer Nvidia has been lobbying for permission to sell China its most advanced semiconductors, the kind needed to run the most cutting-edge artificial intelligence. They seemed to think they had it in the bag; the president signaled that he might put the issue on the negotiating table. On the flip side, many of those worried about the immense danger such sales pose to American national security and economic competitiveness also seemed to think Nvidia was unstoppable.

As it turned out, neither Nvidia nor its dispirited critics were correct. Instead, heeding the counsel of key advisors like Secretary of State Marco Rubio and U.S. Trade Representative Jamieson Greer, the president wisely declined to raise the issue. That decision averted the immediate danger. As John Moolenaar, chairman of the U.S. House of Representatives’ China Committee, memorably put it, selling China advanced AI chips “would be akin [to] giving Iran weapons-grade uranium.” The Trump administration seems to agree, at least for now; Nvidia has been rushing to do public relations cleanup in the aftermath of its setback.

But this temporary reprieve raises the long-term strategic question of what America’s policy should actually be going forward. American Compass’s recently released chip export policy framework, “Stop Selling the Rope: Protecting American AI Dominance from China’s Globalization Playbook,” provides an answer.

Its starting point is simple: America does not have to repeat its past mistakes. It can learn from them instead.

In 2000, the Clinton administration hailed the sale of American advanced technology into China as a “clear win” for the United States. The U.S. and China had just made a deal that would allow China to join the World Trade Organization, which would result in China’s market opening to American investment. The goal was to “allow the United States to participate in building China’s information infrastructure.” High-tech CEOs agreed, with around 200 of them asserting in a letter that exposing “the Chinese to our American business practices, values and perspectives” would ensure that “American firms will be in a position to help shape the continued evolution of China’s economic and social environment.”

One of those things happened: The U.S. most certainly did participate in building China’s IT infrastructure. The second thing did not. Instead, America learned the hard way that China had no intention of playing by the rules. Instead, it would accept American technology for as long as it took to replicate it, seek to displace that technology in the global market, and then weaponize that dominance as a lever of geopolitical power. China’s Huawei is now the world’s leading 5G infrastructure provider.

The same pattern held for many other industries. Solar panels, lithium-ion battery production, rare earth processing—all globally critical technologies that America used to dominate and China now does dominate. The idea that China would remain “addicted” to American technology was profoundly wrong. In industry after industry, the United States traded away global technological strength and domestic economic resilience for short-term corporate profit. One matter that did arise in Trump’s meeting with Xi was China’s threat to restrict rare earth exports to the world, a threat China can only make because it now controls an industry that America once did.

But America hasn’t traded away everything.

In 2025, the United States and its allies still hold a commanding advantage in the design and manufacture of advanced semiconductors capable of powering leading-edge AI. American companies like Nvidia and others dominate advanced chip design. American allies, especially Taiwan, dominate advanced chip manufacture (though more is now being done in the U.S.). South Korean and American companies dominate the production of high-bandwidth memory (HBM), a critical constraint on chip capacity. American, Japanese, and Dutch companies dominate the production of the incredibly complex semiconductor manufacturing equipment (SME) required to produce advanced chips.

This represents functional control of the global advanced AI chip supply chain. Without these chips, which China cannot currently manufacture, America’s advantage in “compute”—the processing power required to run AI models—is significant. China’s own chip production is meaningfully limited; its chips lag at least a generation behind American technology. In other words: America may have traded away global leadership in numerous critical industries, but not this one—yet.

The Chinese Communist Party is desperately seeking to mitigate this disadvantage. The People’s Liberation Army (PLA) sees swift AI development as a primary means to equal or exceed American military capacity. The PLA’s “core operational concept” of “Multi-Domain Precision Warfare” expresses a commonsense realization: U.S. military strength depends on networking that allows its vast capabilities to work together. The quickest way to neutralize that power is to disrupt those connections, and “in the dynamic environment of an actual conflict, identifying and targeting U.S. vulnerabilities” will be a contest of AI capacity and computing power. There is a reason U.S. intelligence believes that “China almost certainly has a multifaceted, national-level strategy designed to displace the United States as the world’s most influential AI power by 2030.”

Absent the capacity to make advanced chips, the quickest way to achieve that goal is to purchase them; the PLA reportedly made multiple requests to purchase Nvidia H20 chips in 2025. The reported $16 billion in H20 chip orders Chinese companies placed with Nvidia during the first quarter of 2025 should be understood in the same way. China’s military-civil fusion strategy renders civilian/military distinctions effectively meaningless—the technological prowess of ostensibly private companies is at the disposal of the Chinese military.

The threat is economic, too. AI represents trillions of dollars of potential value, both from the sale of chips themselves and from the productivity gains AI can drive. The CCP is desperate to embed AI in every facet of economic life, from industry and consumer applications to science and technology, with the goal of creating an AI-powered “intelligent economy”—and ultimately an “intelligent society”—in the next few years.

The most optimistic case is that selling advanced AI chips to China would more rapidly enhance its competitiveness with the United States, fueling the CCP’s stated goal of supplanting the U.S. as the globe’s leading economic and military power. The worst case, especially if chipmakers sell advanced chips to China over American customers—as Nvidia is aggressively lobbying for the right to do—is a zero-sum game in which accelerating China’s economic growth comes at the direct expense of American businesses unable to do the same. It is understandable why an individual chipmaker would want access to the huge Chinese market. It is the job of American leaders to understand that what is good for one company’s short-term interests may not be good for the long-term national interest, and to govern accordingly.

Both on national security and economic grounds, selling the Chinese Communist Party the means to supersede the United States and its allies in the twenty-first century’s most significant general-purpose technology is foolish. The appropriate strategy is not to send the CCP the very technology it needs to achieve its ambitions for global hegemony. It is rather, as the new American Compass framework says, “a policy of full denial of access to the technology that can most effectively accelerate China’s AI progress.” “Stop Selling the Rope” offers guidance on how to best implement such a policy, guided by a “simple, sensible, and urgent” central principle: The federal government needs to prohibit the sale of advanced AI chips and manufacturing equipment to China, working with allies to prioritize American and allied control of advanced AI capacity.

The Trump campaign ran on the promise of being more attuned to the dangers of unfettered globalization than any administration in memory. President Trump’s decision not to offer China America’s most advanced chips, backed by a unified front of senior advisors, was a strong signal that he will live up to that promise with respect to American AI leadership. What matters now is what the administration does next.

Excellent post. We do have a framework in place for this - they are called export control laws. The challenge is setting the boundaries and enforcement (neither of which has been happening for years with the exception of very particular technologies). These laws already provide for civil and criminal penalties with regard to transfer of information as well as articles and materials to persons and companies, as well as specified countries. So we don't need to reinvent the wheel, but we do need to stop selling the rope.

Fine but the big strategic error is not engaging Russia and India in the struggle. Instead we are trying to defeat Russia and force a reluctant India into supporting that effort. All for the sake of the EU/UK who are useless at best and hostile at worst. Nixon had a very good reason for enlisting China in the struggle against the Soviets and it works in reverse too.