Coming Down from the Open-Border Sugar High

Illegal immigration looks good in the economic data, but not to American citizens.

When it comes to illegal immigration, what goes up had never come down. But the lawlessness during the Biden presidency has now given way to an unprecedented reversal, in which the federal government is acting aggressively to secure the border, enforce the law, deport the deportable, and encourage voluntary departures. A new Pew Research analysis of census data estimates that the U.S. immigrant population, after increasing by 11 million between 2020 and 2025, fell by 1.4 million in the first half of 2025.

The economic implications of this reversal are profound. With enforcement now underway, employment and GDP growth are predictably slowing in the aggregate, as continued healthy growth in the permanent and legal economy gets offset by declines in the now-receding illegal segment. Of course, the economic pundits present the slowdown as a negative consequence of unwise policy. The policy is not unwise, and the consequence is not negative. Enforcing the law is necessary, the consequence is natural, and a proper assessment depends now—as it should have all along—on separating the true performance of the permanent economy from the swings induced by triggering mass illegal immigration and then needing to undo it.

True, the surging immigrant population in recent years led to rapid expansion of the labor market. But in doing so it allowed employers to grow their businesses without investing to boost productivity, instead hiring many more workers—easily exploited ones, to be precise—at low wages. That’s not restrictionist rhetoric, it’s the view of liberal open-borders proponents who have celebrated the flood of low-wage labor as ideal for meeting corporate needs and delivering GDP growth while suppressing wages.

A 2024 report from FWD.us, titled To Lower Inflation, America Needs More Immigration, lamented that “when labor is in short supply relative to demand, employers offer higher wages.” Conversely, “immigration policy that responds quickly to market shifts,” it observed, can “offer relief to employers.” At The Argument last week, Jordan Weissmann celebrated how “the historic post-COVID immigration wave” allowed employers to hire quickly without having to increase wages, which might have happened if, perish the thought, “they were posting help-wanted ads in a job market with a serious labor shortage.”

At the time, the influx was presumed to be permanent—a fait accompli, new facts on the ground, that would simply become part of the national baseline going forward. But if one had understood then that the chaos was temporary, and could and would be corrected, the effects look less like beneficial growth and more like an absurd sugar high. Yes, you can generate higher employment and GDP figures by handing work permits to whomever crosses the border. You can achieve a similar effect by legalizing heroin and asking all dealers to fill out their W-2s. In neither case will you have improved the nation’s long-term economic prospects or the well-being of the typical American household.

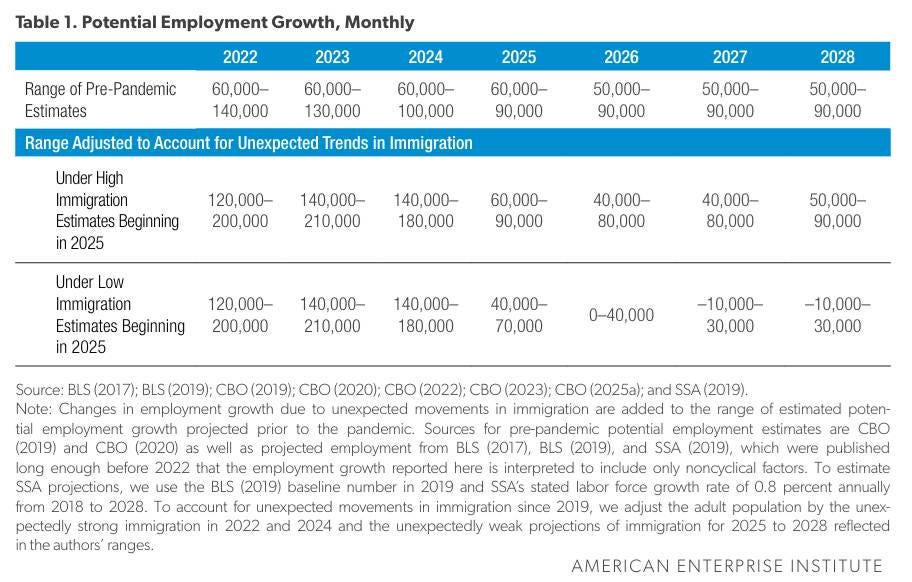

The effect of correcting course is illustrated well in a report published last month by the American Enterprise Institute, Immigration Policy and Its Macroeconomic Effects in the Second Trump Administration, which attempts to quantify the employment effects of the Biden and Trump policies. As a baseline, the authors use Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) and Congressional Budget Office (CBO) forecasts developed prior to 2020 to estimate potential monthly employment growth of 80,000 to 100,000 in the years from 2022 to 2024. The “unexpected trends in immigration” of those years, they find, doubled potential employment growth to 160,000. (I take the midpoints of their ranges throughout; their full table is presented below.) In other words, roughly half of employment growth, and a substantial share of GDP growth, during the Biden administration resulted from the policy failure of border chaos rather than any policy success in promoting stronger economic fundamentals.

For 2025, the authors provide “high” and “low” employment scenarios, with potential monthly growth either returning to the old forecast of around 75,000 in the absence of “unexpected” immigration, or else falling to 55,000 with more robust enforcement creating a headwind from a declining population of illegal immigrants.

But even in that latter case with robust enforcement, the authors never envision the immigrant population falling by more than 525,000 in this full year, which would be less than half the decline that Pew Research reports has already occurred within six months. If the difference between the old base case and the hypothetical modest enforcement is a headwind of 20,000 jobs per month, how low would potential employment growth fall if immigrants are in fact departing at a rate four to five times higher? Probably to roughly zero, reflecting steady continued job growth for native-born Americans and legal immigrants, offset by rapid declines for departing illegal immigrants.

From this perspective, the average of 35,000 jobs added over each of the past three months is substantially higher than could fairly have been expected, not the disastrous slowdown presented in the media. Yet commentators have not only ignored this reality but tried actively to obscure it. Nate Silver, the statistician best known for taking averages of things, has tried to blame trade policy, arguing that “there's been a slowdown since we started implementing the tariffs” by comparing the “average of 182K jobs created a month from Jan. 2023 through Apr. 2025” to the “35K jobs per month” in the past three months. But he has his breakpoint and his causation wrong. Monthly job growth did not reach that 182K average once from January through April of this year; the slowdown was already underway. Stated properly, job growth averaged 191K in 2023–24 and 85K in 2025, and those figures fall squarely in the ranges that the AEI analysis would have expected for each period based solely on shifts in immigration policy. The 35K average of the past three months would likewise be consistent with the more aggressive enforcement underway.

Much debate has centered on the use by the Trump administration and others of BLS data from the Current Population Survey (CPS), which appears to show dramatic increases in the native-born population and workforce alongside dramatic decreases in the foreign-born ones. (I’ve cited that data myself.) As both AEI’s Matt Weidinger and former Biden administration economist Jed Kolko have noted, a number of issues with the CPS methodology make it poorly suited for drawing that conclusion. Fair enough. The problem is that neither indicates any interest in developing a better estimate, though doing so is quite straightforward. The AEI paper that does tackle the question does so only to make the case that enforcing immigration law is costly.

If the goal is simply to maximize the total number of workers in a country and the GDP they produce, enforcing immigration law is indeed costly. But those figures are not ends unto themselves, they are proxies that we expect will show increases when we achieve our goal of sustaining a robust economy that provides family-supporting jobs to American workers and grows their productivity and wages over time. Boosting the numbers without achieving those goals by instead building a temporary, illegal economy atop unstable foundations is a form of fraud. Cleaning up the mess may not look good in the data, but it looks good to the typical citizen.

Hi Oren -- I actually did publish a post that estimates what nonfarm payroll growth would have looked like this year if the foreign-born population declined as much as CPS shows: roughly 2 million fewer jobs over 6 months. The post is here:

https://www.piie.com/blogs/realtime-economics/2025/reported-multi-million-decline-us-immigrants-just-doesnt-add

There is a supporting spreadsheet that lays out all the calculations and lets you simulate a different immigration change if you want. Jed

No mention of masked men shattering people’s car windows and disappearing people. No mention of the continued attempt to eliminate due process. No mention of shipping human beings that made the mistake of trying to improve their families’ lives to be raped and tortured in third world prisons. This deportation policy makes me ashamed to be an American.