The Geniuses Losing at Chinese Checkers

A Silicon Valley model trained on the laziest end-of-history assumptions cannot be allowed to set policy.

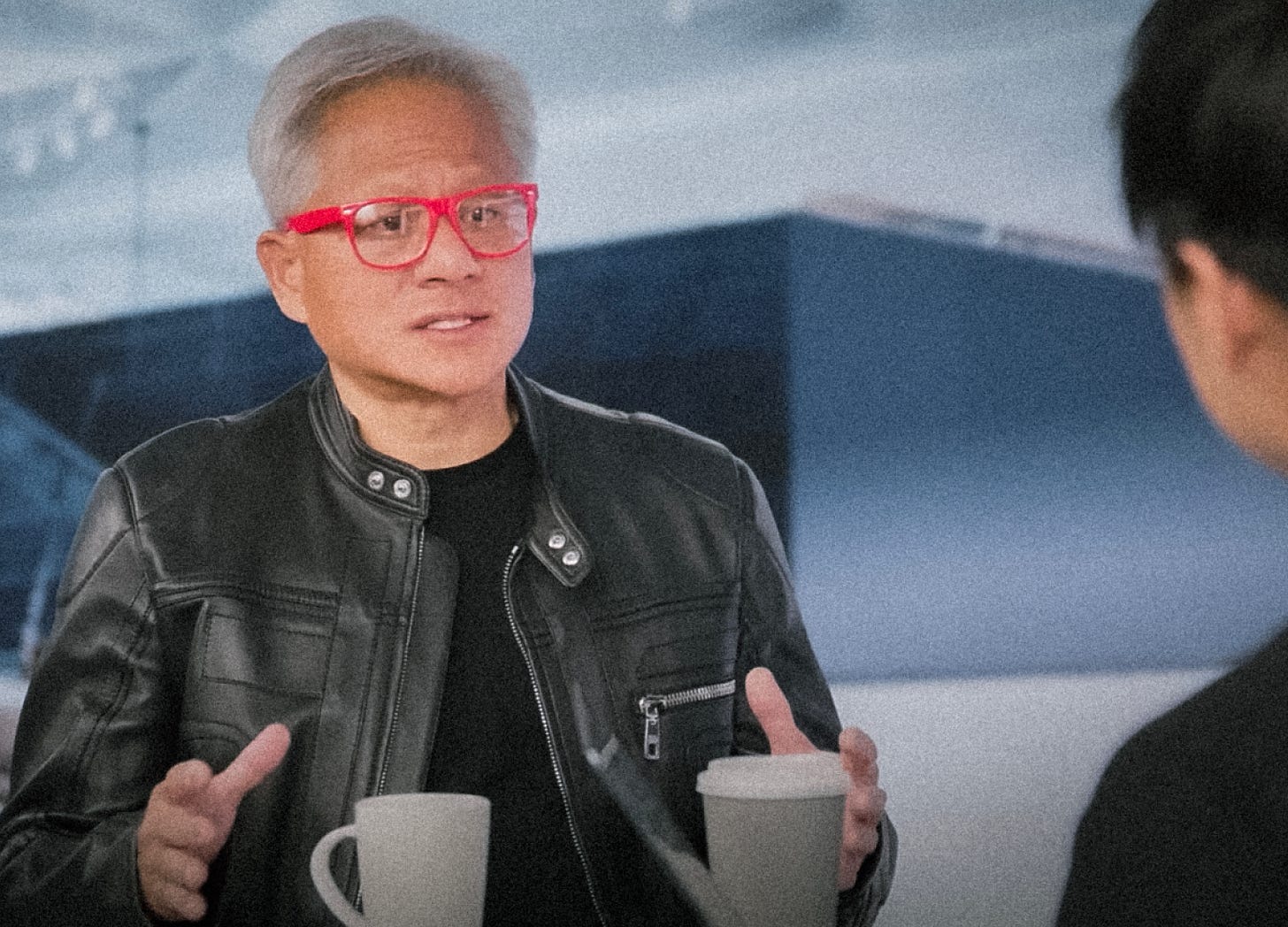

Jensen Huang, interviewed on the BG2 podcast

There is a fine line between ignorance and stupidity, along which the Tech Bro-mance with China has always tiptoed. One sympathizes, surely, with the globalists who believed after the Cold War’s end that embracing China would accelerate its liberalization, or even with Intel CEO Craig Barrett’s conclusion in 2004 that “capitalism has won and economy trumps all going forward.” By the time Elon Musk charged headfirst into Shanghai in 2017, any informed observer could have foreseen the pantsing he would suffer. But some combination of unbounded confidence and naïve optimism is perhaps necessary to sustain the daring entrepreneur in the leaps of faith necessary to build great things.

In 2025, expressing blind faith in the Chinese Communist Party’s commitment to open markets and competition is something else entirely. Who would you guess uttered this comment about China’s leaders, and when: They also publicly say, and rightfully I believe they believe this, that they want China to be an open market. They want to attract foreign investment. They want companies to come to China and compete in the marketplace, and I believe that.

That’s not President Bill Clinton speaking at Davos in the late 1990s, it’s Nvidia CEO Jensen Huang, speaking last week in bespoke red eyeglass frames and his trademark leather jacket to venture capitalist Brad Gerstner on the BG2 podcast. Huang continued:

They want to attract foreign investment. They want companies to come to China and compete in the marketplace and I believe that. … I do hope because they say it—their leaders say it. And I take it at face value. And I believe it because I think it makes sense for China that what’s in the best interest of China is for foreign companies to invest in China, compete in China, and for them to also have vibrant competition themselves.

It’s hard to know what to make of a sentiment so disconnected from reality. Is it just puffery to appease the CCP, while Nvidia’s real defense of selling its chips in China is more nuanced? Others have tried to make a 4D-chess case for helping China gain ground in the race to build AI computing power, arguing that while China will surely insist on developing its own indigenous technology “stack” and driving out foreign suppliers when it can, addicting its developers to the Nvidia ecosystem in the short run will slow down that process. It’s not a good argument, but at least it’s a colorable one.

But Huang has no time for chess. He is playing Chinese checkers. He dismisses the consensus estimate that China is years behind western chipmaking technology, saying, “Is it two years, three years? Come on. They’re nanoseconds behind us.” More broadly, in his view, “everything that has been said so far, that has been made up so far, about China has proven to be wrong. The facts are just wrong. The ground truth is wrong.”

Not that he has any evidence for these claims—how could he? As early as 2010, General Electric CEO Jeffery Immelt was saying of the Chinese, “I am not sure that in the end they want any of us to win or any of us to be successful.” That same year, Google pulled out of China, as co-founder Sergey Brin lamented that “regulations in China effectively prevent us from being competitive.” It took Uber CEO Travis Kalanick less than six months in 2016 to go from bragging:

I was in China 70 days last year, and 100 times a day someone would say, ‘Travis, no Internet technology company has ever succeeded. I don’t know if you should be here.’ As an entrepreneur, that’s the best thing you can hear. … Adventure with a purpose is what we do.

…to abandoning the Chinese market, selling Uber’s business there to the local competitor. As the New York Times summarized, “when American giants tried to enter the waters of China, the world’s largest internet market, the armada invariably ran aground.”

The most recent high-profile victim has been Tesla. As I explained last year in “The Electric Slide”:

Tesla’s market share in China is collapsing, down to just 4% in April, as sales fell 18% from a year earlier despite the Chinese market expanding 33%. China has chewed Tesla up and is now spitting it out. One local provider of automation equipment gloated that “Tesla is like the Whampoa military academy of EVs,” referring to the hallowed institution created by Sun Yat-sen and Chiang Kai-shek in the 1920s that built the new China’s corps of leaders. For his part, Musk is begging American policymakers for protection from Chinese producers, which he calls “the most competitive car companies in the world,” predicting “if there are not trade barriers established, they will pretty much demolish most other car companies in the world.” Tesla’s market capitalization has fallen by more than half.

What is going on here? While this may seem hard to believe, I suspect the simplest explanation is the right one, which is that Huang does not know this history. He’s not familiar with Chinese Communist Party ideology or industrial strategy. He’s a brilliant engineer with the public policy awareness of, well, a brilliant engineer. And he lives in a world of other brilliant engineers and investors who all believe themselves fully equipped to conduct statecraft on the basis of their coding skills and quarterly returns.

Gerstner, interviewing Huang, validates the CEO’s China assessment by assuring him that “you have as much experience or more experience than anyone.” He then says of China’s biggest potential AI users, “let’s be clear with the companies we’re talking about here—ByteDance, Alibaba, et cetera—these are companies that are largely owned by American investors,” to which Huang responds, “yeah, right.” Presumably, if they consider that a useful analysis, they are not aware of the “golden shares” through which the CCP controls Chinese technology companies despite formally owning a stake as low as 1%.

When Gerstner goes on CNBC to pump up his own Nvidia shares, as he did last month, and says, “we want Tesla competing in China,” he is presumably unaware that, for all intents and purposes, Tesla is no longer competing in China. When he makes the case for Nvidia doing business in China by noting, “This is what Google did in the early 2000s… they just went and competed around the world and now the world runs on the democratic principles that are embedded within Google,” he is presumably unaware that Google abandoned the Chinese market, which does not run on democratic principles or on Google. So when he then says of Nvidia’s most advanced Blackwell chips, “I think we’re going to get a big deal done with China, I think it will include Blackwells in China, and it needs to include Blackwells in China in order for the U.S. to maintain its lead,” we should assume a roughly comparable level of coherence.

When Huang, speaking to Gerstner, says of China and its companies, “They should do well. They should give them as much support as they like. It’s all their prerogative,” he presumably is not articulating some heretofore unknown principle of political economy that unfettered subsidies to national champions are consistent with free markets in a global free trading system. He’s just delivering supportive platitudes about the CCP. When he says “I really, really do hope” that President Trump gets a big deal done with China because “decoupling is exactly the wrong concept,” his reasoning really does come down to, “you can’t decouple against the two most important relationships for the next century.”

I cannot prove this. But I can direct readers to a comment Huang makes on the separate topic of immigration. What does he think of the $100,000 fee for an H-1B visa?

The question is, how do we go from the idea that we want to protect fundamentally the American dream to dealing with illegal immigrants at such a large scale? How do we find a logical, pragmatic solution? So the idea that we put a $100,000 price tag on H-1B probably sets the bar a little too high, but as a first bar, it at least eliminates illegal immigration. And that’s a good start.

This is too much even for Gerstner, who cannot help but ask, “How does it eliminate illegal immigration?” Indeed. He suggests Huang meant that it eliminates H-1B abuse, a bailout Huang gratefully accepts, but the windup makes obvious that this is not what Huang meant.

I haven’t taught many classes, but I’ve sat in enough to know what it sounds like when someone hasn’t done the reading. Which in this case, to be clear, isn’t really Huang’s fault. He is understandably busy developing extraordinarily complex technology. Good for him.

But as that work has surely taught him, no amount of raw processing power will convert incorrect training data into good answers. Silicon Valley is still running a model trained on the laziest end-of-history assumptions, captured from Thomas Friedman columns and Davos panel discussions. God help us if “intelligence” of that sort is allowed to set policy and define the national interest.

We do need to decouple from China. Autarchy may not produce maximum efficiency but it is a lot safer than outsourcing critical production to an adversial power. I don't believe in friendsourcing either. America has no friends, just feckless allies starting wars they can't win and attempting to drag us in. So we need to decouple from Europe too. They don't share our values and are anti-American to the core. Trade is OK as long as it doesn't involve anything important to our national interest.

1. US needs a better domestic industrial policy

which also includes

2. Higher levels of skilled immigration