What Color Are the Lights on the Economy's Dashboard?

And more from the week that was...

Today at Commonplace, Chris Griswold writes on Virtue Outsourcing and the Rise of Limousine Populism. The modern Left always seems eager to “the urge of modern societies to offload traditional moral responsibilities onto technological and bureaucratic systems.” But what to call the modern Right’s eager attacks on those systems if it has no alternative?

Welcome to the week. The economy remains front and center in the national debate, as more data pour in each week and partisans on all sides scramble to present each new number as reinforcing whatever they already believed. The predicted catastrophic impact of the tariffs was supposed to be readily apparent by now, and its continued failure to materialize is driving folks a bit crazy. I talked about this at length with Bloomberg Economics’s chief U.S. economist, Anna Wong, on Friday’s American Compass Podcast. I’ve found her to be one of the sharpest and most impartial analysts throughout the past six months, and she provided a terrific overview of what data to watch and what it all means. We also published an excerpt from the interview, highlighting her assessment of what the next few years likely hold.

What We’re Watching Most Closely Is Investment Data. Factory construction, hiring, and output increase will come gradually. But the early indicator will be investment—do firms maintain it in the short-run or are they cutting back? And then, as time goes by, are we seeing a renewal of broad-based investment in the industrial sector or not? Are we getting more greenfield foreign direct investment, signaling that foreign firms have decided it now makes sense to serve the American market from U.S. soil?

The post–Liberation Day figures are just starting to come in, and so far look to be holding steady.

Preliminary Q2 GDP data from the Bureau of Economic Analysis indicated real nonresidential private fixed investment rising slightly, with manufacturing structures down a tick but industrial equipment up a tick.

Monthly Census Bureau data on manufacturers’ shipments, inventories, and orders looks strong. Figures were down in June compared to May, but only because May recorded an enormous one-time bump from aircraft sales. June was up substantially from the prior June and from April.

PMI (purchasing managers’ index) surveys are also a good closer-to-real-time indicator of trends and have also held fairly steady. Both the S&P Global PMI and Institute for Supply Management PMI have show slight improvement over the course of the year, though with pullbacks in July. For S&P, June’s reading was at a 37-month high. For ISM, the manufacturing sector appears healthier in 2025 than in 2024.

Of course, none of this proved an obstacle to commentators with a point to make. They just presented the data as negative anyway. For instance, Noahpinion’s Noah Smith described the upward trend in new orders of durable goods as “deindustrializing.”

The Cato Institute’s Scott Lincicome highlighted a Bloomberg article warning that “manufacturers are increasingly warning that the volatility of President Donald Trump’s tariff policies is crippling decision-making on long-term investments,” complete with charts of the ISM PMI and the S&P 500 Industrials Index both holding steady.

For better analysis, I highly recommend this conversation between Peter Harrell and Brad Setser—two Biden administration alumni who have been among the most honest of brokers in assessing the Trump administration’s policy.

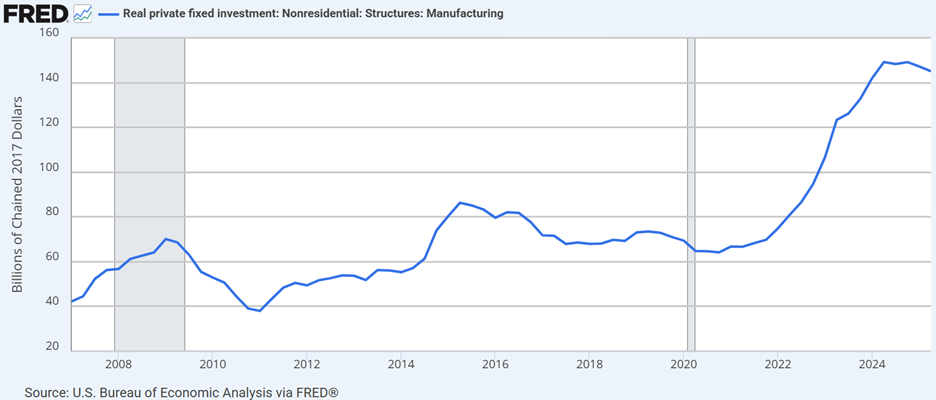

One important question: What constitutes healthy investment? Capital expenditures were already elevated during 2022–24, with investment in manufacturing structures roughly doubling from its prior average, thanks in part to the Biden administration’s industrial policy and the CHIPS and Science Act in particular, before leveling off in the second half of 2024. Would that level have been sustainable under pre-existing policy conditions? If the U.S. economy manages to sustain it now, should that be understood as success, or stagnation?

And here’s another question: What constitutes healthy growth? Mark Zandi, chief economist at Moody’s Analytics, worries that we are “on the precipice of recession,” highlighting that “unemployment remains low, but that’s only because labor force growth has gone sideways” and “fewer immigrant workers means a smaller economy.”

This raises an interesting point: If total employment is rising more slowly because large numbers of illegal aliens are exiting the labor market, often because they are either choosing to leave the country or else being deported, what does that mean for economic analysis? Surely it’s not a sign of a weakening labor market. And if GDP growth slows or even turns negative because labor force growth is slowing—fewer workers equals less output, all else equal—what are the implications for our concept of a recession? If what we care about is not some abstract number of jobs or level of GDP, but rather the well-being of the typical American worker, then the relevant measures are the unemployment rate, wage growth, and productivity growth.

That said, a contracting economy would create a difficult environment for investment, hiring, and so on. But that said, if a temporary contraction is the price to be paid for correcting 30 years of irresponsible trade and immigration policy, it is a price worth paying, and one best paid quickly. As I wrote back in March, That Reagan Guy Started with Quite a Recession, You Know.

President Trump, meanwhile, continues to show interest in expanding temporary worker programs and allowing illegal aliens to “touch back” to their home countries and then return to continue working. This would blunt the labor-market impact of immigration enforcement, avoiding reductions in the workforce but, rather relatedly, avoiding any pressure on employers to create better jobs for American workers.

Up Next: The July Consumer Price Index release is on Tuesday. We’ve been hearing for several months that next month is the month that price increases really start showing up in the data. Will this be the month? I suspect we will continue to see gradual increases. Back of the envelope, an effective 15-20% tariff rate across all imports, with some but not all passing through to consumers, is worth around one point of total CPI increase, most likely appearing over the course of a year or more. And once it fully phases in, because the tariff is a one-time level change in prices, CPI growth should start coming back down again. The price effect will happen, but never in the dramatic form tariff opponents keep anticipating.

TARIFF CORNER

What else is happening with tariffs these days?

Transshipment: China’s export machine continues to churn; total exports are up, exports to the United States are down. The Wall Street Journal reports, “Chinese outbound shipments rose 7.2% last month from a year earlier on a dollar-denominated basis, up from a 5.8% increase in June... Exports to the U.S. fell 22% in July from the year prior, according to the government data. That compared with a 16% decline in June and a 35% drop in May.” But as CFR’s Brad Setser observes, the initial result of the tariffs on China has been to shift the source of U.S. imports from China to other Asian economies, suggesting that in many cases just final assembly is moving (or fraudulent transshipment has been at work).

Importantly, the agreements struck with those other Asian economies may set tariffs based on how much Chinese content is present in any final good, which would dramatically increase incentives to move supply chains out of China entirely.

Investment funds: Speculation continues over the massive investment commitments made by U.S. trading partners—reportedly including $550 billion from Japan and $350 billion from South Korea. Is this cash? Loans? Foreign direct investment (FDI)? Michael Pettis has an excellent thread laying out the problem with securing cash commitments in deals aimed at reducing the trade deficit. “Telling countries to choose between reducing their trade surpluses with the US or increasing their investment in the US suggests a very muddled understanding of trade,” he warns. “It is precisely because these countries have implemented domestic trade and industrial policies that result in trade surpluses that they must invest abroad, and it is because they prefer to invest that money in the US that the US must run the corresponding deficits. What the US needs is more foreign demand, not more foreign investment. The two are not equivalent.”

I would offer one addendum: the exception to this rule is if foreign companies are doing real greenfield FDI in the United States. Almost all of what gets called FDI is just foreign acquisition of American assets. But when foreign corporations come set up shop here to serve our market (think Toyota and Honda in the American South), that is a vital long-term step toward rebalancing trade. TSMC’s investments in Arizona right now are a great example. Maybe the investment puts upward pressure on the trade deficit in the year it occurs, but over time that investment will pay dividends many times over in the other direction. The US needs foreign demand; it also needs domestic production to serve domestic demand.

Apple also made encouraging news last week, announcing a new commitment to domestic investment far more promising than the typical fare. Apple in China author Patrick McGee (who joined me recently on the American Compass Podcast) says that “the additional $100bn is far more detailed than the prior three announcements citing much higher investments. Suppliers, cities, projects are named. A good sign.” Specifically, Apple says all Corning glass for its phones and watches globally will now be made in Kentucky.

And then there’s Jensen. But breaking over the weekend, another visit to the White House by Nvidia CEO Jensen Huang has prompted the Trump administration to begin issuing licenses for the sale of H20 chips to China, now with the bizarre proviso that Nvidia will pay a 15% tariff on the chip sales in China to the U.S. government. (Same goes for a similar chip from AMD.)

Issuing the H20 licenses at all is a grave error by the administration, for the many reasons described in the letter by a range of leading national security experts that American Compass co-lead with Americans for Responsible Innovation. For years, American business leaders believed that transferring technology to China would secure them a lasting foothold there. They were duped, and then discarded as soon as China developed indigenous alternatives. The U.S. government is now making the same mistake, in the futile hope of a lasting American advantage. The result will be to slow American progress, accelerate Chinese progress, and drive up the share price of multinational corporations at the expense of the national interest.

The 15% tariff adds insult to injury—quite literally, in that it takes what was a substantively damaging decision and makes it kind of embarrassing. The agreement is being widely panned by, well, everyone, as incoherent, likely illegal, and the reductio ad absurdum of policy-by-dealmaking. The whole point of export restrictions is to accept an economic cost for the sake of national security. As Liza Tobin, who served on the National Security Council in the first Trump administration, put it, “Beijing must be gloating to see Washington turn export licenses into revenue streams. What’s next — letting Lockheed Martin sell F-35s to China for a 15 per cent commission?” It’s hard to think of a clearer example of selling out the national interest for a quick buck.

GOOD READS

Thinking Is Becoming a Luxury Good | Mary Harrington, New York Times

Picking up on a favorite U/A theme, Harrington writes, “making healthy cognitive choices is hard. In a culture saturated with more accessible and engrossing forms of entertainment, long-form literacy may soon become the domain of elite subcultures.”

The Disappearing Court Packers | Parker Thayer, Capital Research

Remember all those organizations insisting that we needed to expand the Supreme Court to strengthen democracy? Were you wondering how many are still arguing for their reform now that Donald Trump is president again? No? Me neither. But this is still a fun romp through the debris.

The Autoworkers Want Their Union Back | Frannie Block, The Free Press

Searching for growth, the UAW now counts more than 100,000 workers from academia among its fewer than 400,000 total members. That has proved an awkward fit. Also, check out Teamsters president Sean O’Brien on Bari Weiss’s podcast.

Why We Remade the Global Order | Jamieson Greer, New York Times

The U.S. Trade Representative lays out the logic behind the administration’s strategy.

IN OTHER NEWS

The Realignment Comes for Israel: The sharp shift in attitudes toward Israel within the Democratic Party has attracted more attention, but a rethinking is underway on the Right as well. UnHerd had an excellent piece from Emily Jashinsky on the issue, as well as a robust debate between Sohrab Ahmari and Batya Ungar-Sargon

An Encouragingly Not-Insane Thought: “Right now, [the United States] is letting corporations route young men to online sports betting, pornography, and social media—it’s all digital rewards and no real-life effort. Young men are the worse for it, both in the job market and the marriage market.” – Rep. Jake Auchincloss (D-MA).

Speaking of men in the labor market, the Manhattan Institute’s Allison Schrager writes, “While the overall unemployment rate was still a respectable 4.2% in July, for young men aged 20 to 24, it was 8.3%, which is near recession levels — and for recent college graduates, the annual rate is 5.3%. Both of these numbers are about double the comparable figures for young women.”

And at Harvard: The Trump administration opened a new front in its fight with Harvard University, this time over patents developed from federally funded research. Fun fact: the Bayh-Dole Act of 1980 imposes all sorts of requirements on such intellectual property, including that products using it be manufactured in the United States. Sounds like a rule worth enforcing!

American Affairs published a great essay on the issue a couple of years back:

Forty years later, even the Bayh-Dole Act’s explicit attempts to ensure public use of relevant technology rights have failed. One requirement is that licensees of government-funded technologies manufacture those products in the United States, but nearly all, if not all, applications for waivers of that requirement appear to be granted at least in the pharmaceutical space, allowing a category of drug patent holders to rake in massive profits from government-funded research while outsourcing the drug and active pharmaceutical ingredient manufacturing to India and China.

And hey, speaking of Israel, may I recommend American Compass’s fine case study on the Israeli policy that made a sliver of land in the desert one of the world’s leading tech ecosystems—featuring a robustly enforced requirement for keeping the nation’s IP in house.

Keep an eye on… the absurd balkanization of live sports streaming, as the NFL season comes around and viewers discover they have to pay through the nose for countless services just to follow the sport.

Did you know… airlines lose money actually flying planes, but generate a profit selling credit-card miles. I was once at dinner with a credit card executive who was trying to defend the absurd processing fees charged by his industry. If we regulate away the fees, he warned, customers will lose their rewards programs and be furious. I politely suggested that he could still make any customer who might like the status quo a straightforward offer: a 3% surcharge on their credit card bill and continued accumulation of the various points and miles. What share of customers, I asked, did he think would opt into that program? He struck up a conversation with the guest on his other side.

Enjoy the week!

Oren, you're going to lose readers and credibility if you keep making statements like this: "The predicted catastrophic impact of the tariffs was supposed to be readily apparent by now,"

The tariffs were announced April 2 IIRC, then debated and changed over and over, and now, in early August MIGHT be stabilizing. SO, the full impact will not be felt for months, perhaps into next year, given supply chain lags. What we do know is that the UNCERTAINTY of the tariffs just resulted in the worst quarterly jobs report since Trump mismanaged the pandemic. And that's saying something. But again, that could also be federal job layoffs and university researchers fleeing to countries willing to invest in research, and not tariffs. We also saw oligopolistic pricing kick in as domestic producers raised prices knowing foreign competitors' prices would be higher (e.g. steel). You're headed to clickbait territory jumping to conclusions. Why don't you just produce a "scorecard" or Dashboard of the Top 10 things to watch, and let's watch that for 6 months?

I love irony. It's so fitting that Oren recites a laundry list of government stats at a time when Don has just fired the commish at the BLS for the crime of telling the truth about government stats:) Makin Kim Jong Un envious...

Meanwhile, here's my reading recommendation for the week, odd that Oren missed it. Make sure and read the CBO report on the BBB, the crowning legislative achievement of DonOrenomics and the "new" right. It's chock full of non partisan detail on the bill's regressive nature. Rich folk do quite well, workin slobs not so much. Yet, we were assured it was all about the downtrodden workin stiffs... The rhetoric sure sounded good, but when the time for action came, we received the revealed preference:)

As a self anointed champion of the working class, it seems Oren might muster an opinion at some point?